Already this year, Qatar has celebrated not one but two credit rating upgrades. Both Moody’s and Fitch raised the sovereign’s credit rating one notch, to Aa2 and AA. Standard & Poor’s already rated the country AA, giving Qatar the full complement of double-A ratings. The underlying drivers of the latest upgrades are a combination of Qatar’s phenomenal gas deposits, combined with a savvy fiscal prudence.

Between 2026 and 2028, Qatar is expected to increase liquefied natural gas production from its North Field deposit — the largest gas deposit in the world — by a staggering 60%. There will be a further increase — smaller but still significant — of 18% between 2028 and 2030.

The oil and gas sector provides a huge chunk of government revenue, and LNG comprises the great majority of hydrocarbon exports. The sheer scale of the planned LNG increase is remarkable, and will give Qatar room to maintain the same level of revenue even if prices decline.

At the same time, the government is steadily unwinding the massive infrastructure capital expenditure programme it enacted to prepare for hosting the FIFA World Cup in 2022.

During 12 years of preparation, the country built hundreds of hotels and thousands of new homes, as well as a series of massive stadiums and conference centres. Reports have estimated Qatar’s investment to prepare for the competition at over £200bn. Having created world class telecoms, transport and hospitality infrastructure, the authorities are returning to a more circumspect approach to spending.

“Our upgrade was based on high confidence that the North Field expansion will bring a large amount of new budget revenues, and similar confidence that spending will not rise at the same pace,” says Cedric Berry, director of EMEA sovereign ratings at Fitch Ratings in Hong Kong.

Driving diversification

There is no doubt hydrocarbons will remain the most important sector in Qatar’s economy and a bellwether for the health of government revenue.

But their contribution to GDP fluctuates with oil and gas prices. Even though LNG exports are far more valuable to Qatar than crude oil, the price of oil still matters. Alexander Perjéssy, senior sovereign credit officer at Moody’s Ratings in Dubai, notes that in 2023 when oil prices averaged $83 a barrel, hydrocarbons provided 39% of Qatar’s GDP. Between 2011 and 2014, when they averaged around $110, hydrocarbons contributed 55%.

Ultimately, the ramp-up of LNG production means that even if oil and LNG prices fall, the contribution of hydrocarbons as a percentage of GDP is not going to decline significantly over the next few years.

A single sector providing close to half of GDP could appear problematic from a diversification perspective. But there has been real growth in the non-oil sector in recent years. “Since 2013, the non-oil sector has grown by roughly 40%, whereas the hydrocarbon sector actually contracted by nearly 6%,” says Perjéssy.

Construction sector growth has been huge. The rush to build hotels, offices, stadiums, conference centres and other infrastructure almost doubled the construction sector in the 10 years to the World Cup. There is now an oversupply of some kinds of real estate — notably hotels — suggesting construction growth will moderate. But the size of some of the infrastructure projects in Qatar’s pipeline means construction and infrastructure will remain a major driver of the non-oil economy.

“Qatar has continued its rapid infrastructure development,” says Sheikh Abdulrahman bin Fahad bin Faisal Al Thani, chief executive officer of Doha Bank. He points to the recently announced QAR20bn ($5.4bn) Simaisma project. The 8m square metre development will create a new tourism hub with a golf course, theme park and 7km of waterfront.

“In addition to this mega-project, many other infrastructure development projects will continue to support economic diversification and growth,” says Al Thani.

Bassel Gamal, group CEO of QIB, is expecting robust investment in infrastructure projects to enhance connectivity and support economic diversification. “QIB is committed to financing key infrastructure developments, helping to facilitate the construction of roads, bridges and public facilities that contribute to the nation’s long term vision,” he says.

The creation of free trade zones and industrial development is also driving construction sector growth.

“Qatar is strategically enhancing its industrial development by establishing various free zones to attract foreign direct investment and foster a diverse economic landscape,” says Al Thani. “These zones focus on emerging technologies, logistics, industries and maritime. Investment-friendly policies such as 100% foreign ownership, zero income tax and corporate tax exemptions make Qatar a destination of choice and will support economic diversification.”

Knowledge economy

But strong underlying growth in the non-oil sector is not confined to construction. Information and communications technology (ICT), transport, real estate and finance have all grown significantly. “In terms of comparison with the rest of the region, there’s been broad-based growth across different sectors,” says Perjéssy.

ICT will continue to evolve, as powerful artificial intelligence and cloud computing tools are incorporated across the economy. Qatar — with its access to cheap power — is perfectly placed to act as a hub for the growth of energy-hungry computing power.

A spate of ICT projects have been ann-ounced over the last year or so, and many more are expected in the coming years.

Al Thani notes that Qatar National Vision 2030 is the cornerstone for developing the knowledge economy and innovative society. QNV 2030 has four pillars: human development, social development, economic development and environmental development. “The progress made has been exciting,” Al Thani says, “and continuing the same trajectory will help us transition to becoming a truly knowledge-based society.”

Gamal at QIB agrees: “We see great potential in the knowledge economy as Qatar continues to diversify its economic base,” he says. “The emphasis on innovation and technology will drive growth in sectors such as education, research and digital services.”

In trying to grow non-oil sectors like tourism, ICT and conferences, Qatar is in competition with its neighbours — most of which are pursuing growth in the same industries.

But Qatar faces less pressure to diversify as quickly as possible. This is where its relatively small size and population — under 3 million — act in its favour. Saudi Arabia’s population is over 35 million and even Oman and Kuwait have roughly twice as many people as Qatar.

More significantly, Qatar’s neighbours have a far larger share of citizens in the total population — the volume of new jobs that needs to be created to ensure political stability is proportionally higher.

“In Qatar, the estimates are that the local population constitues anywhere from 10% to 15% of the population and only around 6% of the labour force,” says Perjéssy. “That compares with north of 60% in Saudi Arabia, over 55% in Oman and more than 30% in Kuwait.”

Qatar’s public and private sectors are in a much better place to absorb the new cohorts of citizen graduates entering the labour force.

Loan growth moderates

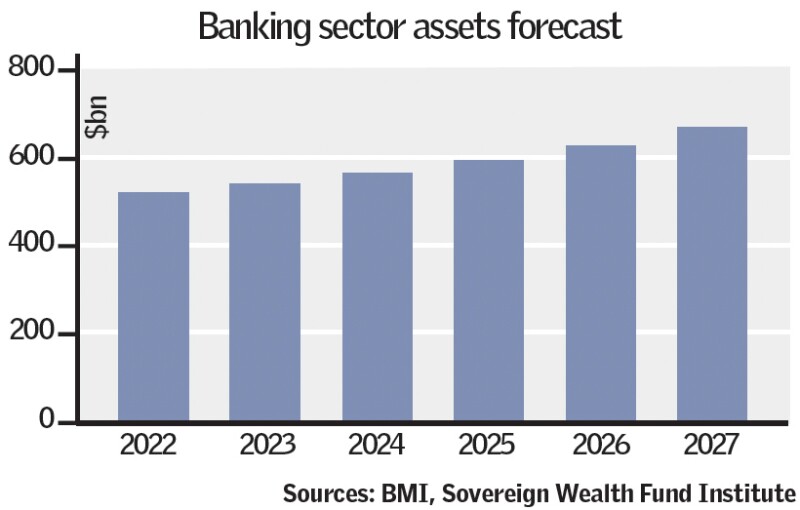

A growing private sector needs a strong banking sector. Qatar’s lenders — with their large balance sheets, impressive profitability and solid capital ratios — are well placed to support firms, from small and medium-sized enterprises to major corporations.

Loan growth, however, has been lacklustre recently. At the end of 2023, aggregate loan growth across the banking sector fell to a historic low of 2.8%, according to Fitch.

This is partly to do with the unique make-up of Qatar’s economy. When LNG prices rise — as they did sharply after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — so do government revenues. The government has used some of this increase in revenue to pay back bank loans. At the same time, the frenetic economic activity that heralded the World Cup has tailed off.

But analysts are expecting loan growth to rise. Francesca Paolino, lead analyst for banks at Moody’s Ratings in Dubai, says Moody’s forecasts loan growth of 3% to 4% in 2024 and 2025. Fitch expects 4% credit growth in 2024 and 5% in 2025.

Paolino says loan expansion will come mainly from projects associated with the increase in LNG production capacity, but also from sporting events, business exhibitions and other related economic activities.

The Formula 1 Qatar Airways Qatar Grand Prix, Artistic Gymnastics World Cup and the final of the Beach Volleyball World Pro Tour are just a few of the events taking place this year.

Nor is slower loan growth necessarily a problem. A more modest increase in credit to a broader range of economic sectors is far more welcome than a more rapid expansion of lending concentrated in a single, high risk sector.

Managing banking risks

Unsurprisingly, in a country as small as Qatar there is large concentrated exposure to certain sectors and individual borrowers. This in turn exposes banks to unexpected shocks, particularly if these sectors are relatively illiquid. One in particular keeps analysts awake at night — real estate. They foresee slight — but not serious — weakening in loan performance due to overcapacity. The main culprits are shopping malls and office buildings.

“In Qatar, the recent weakening in loan performance is mainly attributed to overcapacity in the real estate sector — shopping malls and office buildings — and in the service sector, mainly hotels.

A more severe weakness in the real estate market will have a significant impact on the banking sector because of the concentration — real estate and contractors represent one-fifth of the Qatari banking system’s aggregate loan portfolio,” Paolino says. “At the same time, we do see the regulator very actively moving to address that issue. They have issued new policy measures that should help monitor and mitigate the high risks in this sector.”

Another perennial issue for Qatar’s banking sector is reliance on external funding. Net foreign liabilities increased very substantially between the end of 2017 and mid-2021, when the central bank tightened regulation. These liabilities have declined, but are still sizable.

“Qatar banks’ overreliance on confidence-sensitive foreign funding has been declining following implementation of prudential regulations, but the level still remains high — 33% of total liabilities as of June 2024,” Paolino says.

Analysts, however, take comfort from the fact that the government has access to large foreign currency reserves and liquid assets, held at the sovereign wealth fund, the Qatar Investment Authority.

As the government demonstrated during its blockade by other Arab states in 2017, these sources can be called upon to close both a gap in the banking sector’s balance sheet and any balance of payments shortfall that might put pressure on the currency.

The central bank has also taken steps to force banks to lengthen the maturities of their external liabilities. That at once reduces the risk of capital flight and makes its possible impact on the financial sector less severe. Ultimately, the regulator will make sure banks’ external liabilities decline and lengthen.

Risks recede

This is salient because the main risk to Qatar’s macro-economic stability is geopolitical. There is a possibility — however slight — that events might make it difficult or impossible for Qatar to transport its LNG to its customers in Asia and increasingly in western Europe.

Qatar shares this risk with many of its neighbours in the Gulf Cooperation Council, which export oil and gas through a single choke point — the Strait of Hormuz. Nor does Qatar have — as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates do — any pipelines that bypass the strait, which Iran has threatned to close many times in the past.

The four year blockade that began in 2017 when several of Qatar’s neighbours tried to pressure it into a series of political concessions also looms large in the memory.

But analysts say the GCC and its rulers have gained a great deal of experience since the blockade — which failed to prompt any policy change in Qatar.

Gulf leaders have to chose carefully between their long term economic goals and short term geopolitical priorities. There is a sense that the heads of the various countries believe regional confrontation will not generate results. “The risk of a blockade as in 2017 is very low,” says Berry at Fitch. “It seems that everyone is much more focused on business than brinkmanship.”