2024 was the year when Egypt pulled itself back from the brink.

The financial and economic crisis that had struck in early 2022 was by no means entirely of its own making. Russia’s war against Ukraine sent food and fuel prices spiralling, at a time when Egypt was only just recovering from the Covid pandemic.

But at its core, the crisis was due largely to Egypt’s determination to keep its currency overvalued by using fixed exchange rates. As foreign direct investment fell, support from partner countries in the Gulf dwindled and remittances declined, this became untenable.

To their credit, the authorities have stepped up and done what was necessary. Egypt’s pound — long pegged at E£30 to the dollar — was freed, and sank to E£50 almost overnight. To contain inflation, the central bank has steadily hiked its overnight deposit rate to 27.5% — up from 16.25% at the start of 2023. The government has promised to privatise a string of state-owned companies and create a level playing field for a neglected private sector.

These are all things Egypt’s multilateral and bilateral donors not just wanted — but needed — to hear.

The days when financial support could be obtained without a credible commitment to reform are gone. In February, the government announced a $35bn agreement with the United Arab Emirates, of which $29bn is for the right to develop Ras al-Hikma as a resort on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast.

But no one thinks the UAE would have signed the deal if it did not believe Egypt was serious about privatisation and currency reform.

A few weeks later in March, the long-awaited devaluation paved the way for an expanded programme with the International Monetary Fund, increasing its support to $8bn.

“Egypt’s investment landscape has witnessed significant improvements, with large inflows of external funding,” says Islam Zekry, group chief financial officer at CIB. “The authorities have demonstrated their steadfast commitment towards enhancing Egypt’s economy.”

Policy makers are adamant that the devaluation signals a new era for monetary policy, in which the market — not ministers — will set the exchange rate.

Some six months later, the market is still in charge. Analysts at BMI say the spread between the black market and official FX rates averaged E£0.6 in July, and rose only slightly to just over E£1 in August.

Investors have also been heartened to see the government retain and promote economic officials with real skill and expertise. In July, Ahmed Kouchouk was made finance minister, having been vice-minister for fiscal policies and institutional reform and the country’s chief negotiator with the IMF since 2016.

In August, President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi extended Hassan Abdalla’s appointment as acting central bank governor for a third year. Abdalla was originally appointed for a single year in August 2022, which was extended in 2023. “The central bank and Ministry of Finance teams are very good,” says Angus Blair, CEO of Cairo-based thinktank the Signet Institute.

Positive impact

The benefits of these changes for facets of the economy have been undeniable. Remittances are Egypt’s main source of foreign currency and a barometer of the health of the economy.

The $29bn Ras al-Hikma development deal might seem colossal, but remittances to Egypt in 2021 were over $31bn.

The massive gap between the official and black market exchange rates — along with worries about the fundamental future of the Egyptian economy — had sent remittances spiralling down.

In the second half of 2023, less than $10bn was sent back to Egypt. But remittances have surged back, totalling $7.5bn in the second quarter of this year — a 60% increase on the same quarter in 2023.

This recovery should help narrow the current account deficit — or at least, stop it getting wider. This is where Egypt is at the mercy of geopolitical volatility. In the second quarter of this year, Egypt made a $3.7bn deficit. Analysts noted that Suez canal receipts were only $870m — down from $2.5bn in the same quarter last year.

This is largely due to Yemen-based Houthis launching attacks on Red Sea shipping — ostensibly to protest against the war in Gaza. Suez Canal receipts are another source of foreign currency. International tensions also spook foreign portfolio investors, which BMI analysts note now hold almost half of all Egyptian T-bills with maturities of 12 months or less.

An end to the war in Gaza might allow an increase in commercial shipping through Suez and open the door for Egyptian companies to engage in reconstruction work.

But should regional conflict worsen, it could drive foreign investors away, weakening the pound and pushing up inflation. Tourism — another vital source of FX — would also be affected.

So far, it has held up well despite the political turmoil. Tourism minister Ahmed Issa said earlier this year that 3.6m tourists had visited in the last quarter of 2023 — the second highest figure for the fourth quarter.

“Egypt’s tourism sector has recovered significantly from the Covid-19 pandemic downturn, recording over 7m visitors in the first half of 2024,” says Zekry at CIB. “This sector is regarded as the main source of national income and positively contributes to job generation and enhancing the country’s foreign exchange reserve.”

Egypt aims to attract 30m tourists a year by 2028. The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities is rolling out policies to hit yearly growth rates ranging from 25% to 30%.

GDP recovers

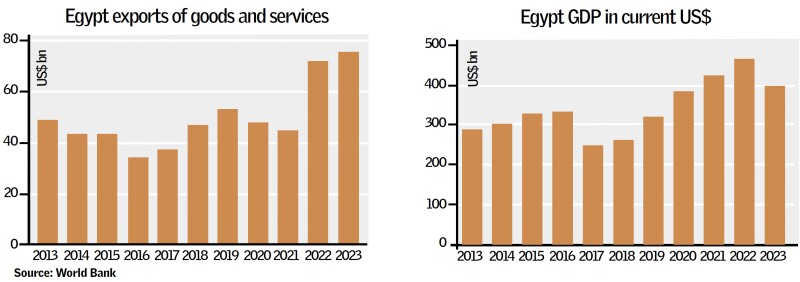

All this has lifted GDP forecasts. BMI analysts are expecting growth in Egypt to hit 4.2% in 2024-25 — although this assumes an end to the war in Gaza by the close of 2024.

S&P Global economists have a similar projection for 2024, but see growth rising to 5% in 2025 and 2026. The main domestic drivers are likely to be an increase in investment and a strengthening manufacturing sector.

“Adjustments in the exchange rate, alongside FDI, have significantly reduced foreign currency market dislocations and injected fresh investor confidence and growth,” says Zekry.

Improving short term investor confidence is one thing. But reforming the economy to create a prolonged surge of FDI into higher value-added sectors is quite another.

Still, Zekry says the Egyptian government understands the importance of FDI in addressing economic challenges. “The government has implemented numerous regulatory and legal reforms to enhance the country’s business climate,” he says, pointing to a programme to reduce the state’s involvement and boost private sector investment. “These reforms aim to enhance investors’ ability to conduct financial transactions, obtain legal residence, establish duty-free zones, develop investment incentives for certain investment projects and eradicate preferential taxes for the majority of state-owned businesses.”

The authorities have created new investment incentives and extended a ‘golden licence’ programme to help launch new infrastructure and industrial projects aligned with specific criteria.

“The golden licence tackles the full process of establishing a project and includes managing and operating the project, allocating the land and building licences,” says Zekry.

Rania Al-Mashat, Egypt’s Minister of International Cooperation, says that improvements in the balance of payments, bolstered by structural reforms and a recovery in net portfolio investments, all signal increased economic stability and predictability. “These are key factors that encourage long-term capital,” she says. “Egypt’s recent macroeconomic achievements will significantly improve its investment landscape by creating a more stable and attractive environment for both domestic and foreign investors.”

Certain sectors are getting a regulatory overhaul. The country has a new mining law that applies to commercial discoveries made across an area of almost 3,000km2. Gold miners Centamin and Barrick Gold and consultants Wood Mackenzie helped Egypt draft the legislation, to overhaul an out of date system of oil and gas-style concessions.

Centamin CEO Martin Horgan has spoken approvingly of the new regime that — with a 5% royalty, 22.5% tax rate and 15% government free-carry — mirrors those in most other countries.

As well as significant gold deposits, Egypt has major stores of other valuable minerals like iron ore, phosphates and tantalum — used in computers and laboratories. But the data show that investment in mining exploration is hardly growing.

Mining industry figures expect the new law to help attract more foreign firms to Egypt and create a more developed ecosystem of supply chains and service providers.

Top: The central business district of the New Administrative Capital east of Cairo

Bottom: Hamama gold exploration site deep in the desert east of Luxor; Extending the Mediterranean harbour with a new port terminal, Alexandria

Progress on privatisation

Another plaudit for Egypt’s authorities is for progress on privatisation. In mid-2023, the government announced it would sell holdings in a range of state-owned firms.

Investors, however, have heard statements like this before. Some of the planned asset sales have been in the works for decades. “With a few exceptions, the privatisation programme has been in all but stasis,” says Angus Blair. “But now there is very significant pressure from the IMF, other global interlocutors such as the EBRD, and from investors.”

In December last year, the prime minister announced that Egypt had raised $5.6bn from selling stakes in 14 companies, in sectors including industry, tourism and energy.

Ben Fishman, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, noted in May this year that most of the buyers were Emirati entities and private Egyptian firms close to the government that focused on acquiring hotels. “For now, the most valuable state-owned companies remain unsold, including banks and insurance firms,” he said.

Egypt has also revised downward its target for asset sales in 2024 and 2025, after the inflow of funding from the UAE. It was originally aiming to raise $6.5bn, but now intends to sell only $2.5bn.

Still, recent media reports suggest the government is in the advanced stages of selling its remaining 20% stake in the Bank of Alexandria to Italian lender Intesa Sanpaolo, which already owns the other 80%.

In September, Egypt announced the sale of 100% of microfinance lender Tamweely to a consortium of investors consisting of SPE Capital, Egyptian firm Tanmiya Capital Ventures, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and British International Investment.

Wind turbines at Lekela wind power station, near the Red Sea city Ras Ghareb

At the margin, these privatisations will bolster investor confidence that this time really is different. But proof is going to be far more important than promises. Markets have been waiting for Banque du Caire’s privatisation for over 10 years.

This is where pressure from Gulf investors could help ensure a level playing field. In September, the Egyptian government said Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had instructed the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) to direct $5bn of investment funding to Egypt, as a “first stage”.

Egypt watchers noted that on a previous visit to Riyadh, Egypt’s prime minister had had to explain to investors and the Egyptian-Saudi Business Council the progress made by a special unit designed to resolve complaints from Saudi investors in Egypt. Gulf states like Saudi are happy to invest — but they now need assurances that they will be treated fairly.

Export potential

Another feature of the government’s economic reform plan is expanding exports. Egypt is committed to investing in industrial development to encourage local production and increase the competitiveness of Egyptian products.

Zekry argues the country’s geographic location, climate, population and diverse economic landscape provide tremendous export opportunities. “These factors are augmented by a cost-competitive labour force as well as cost-competitive university graduate population,” he says.

For years, Egypt’s economy has been held back by the dominance — some would say interference — of state-owned firms. But there are still industries that hold huge potential for the private sector. Car manufacturing is one. Egypt might lack the financial resources of a Saudi Arabia — which has successfully attracted original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to set up production facilities. But it is still making headway after some false starts.

Various projects to launch local

electric vehicle manufacturing in Egypt were announced in 2020 and 2021 but were subsequently cancelled. Currency movements and the high price of imports likely played a role in these failures.

The Benban Solar Energy Park in Aswan

“Global OEMs reduced or stopped exporting to Egypt due to concerns about payment and a preference for exporting to countries with lower financial risk,” says Michel Jacinto, a senior associate analyst in S&P’s Global Mobility business. Economic volatility sent demand for new cars in Egypt plummeting — by more than 35% in 2022 and almost 50% in 2023.

With a new era of economic reform ahead, there are signs of fresh attempts at EV offerings. GV Auto, a subsidiary of Egypt’s GV Investment Group, announced in May that it would partner with Chinese manufacturer FAW Group to start producing EVs in 2025. Not only does GV Auto hope to use a large proportion of local components, but it wants to establish a platform for exports.

“Through the Automotive Industry Development Plan, Egyptian authorities aim to position [the country] as a significant assembler in the African market,” says Mieko Hongu, a senior research analyst for S&P Global Mobility.

But she notes this transition will largely depend on regulatory developments across African markets, which lag behind global trends. “Before transitioning to electrification, Egypt must develop a robust automotive production environment, enhance its supply chain, and achieve greater scale,” she adds.

In the MENA region, Morocco is an example of a country well positioned in many essential stages of the automotive value chain, from raw materials to manufacturing and supply. But this does not mean Egypt cannot follow suit — its population is three times the size of Morocco’s and scale is a crucial factor.

“Services, such as tourism and transport, medical services, technology and communications, as well as outsourcing all have export potential,” says Zekry. “By deliberately investing in the above sectors, Egypt can boost its export prospects and aggregate economic growth.”

Building out export potential in turn necessitates improvements in skills and productivity. Al-Mashat at the MIC notes that Egypt’s continued fiscal consolidation is expected to enable further investments in human capital and industrial development. This in turn will enhance productivity — a key driver of sustainable economic growth.

“The government’s ongoing implementation of reforms and the focus on strengthening public investment governance are paving the way for more private sector engagement,” she says.

For its part, the MIC is focussed on formulating data-driven and evidence-based economic development policy. “The ministry is committed to fostering informed discussions on the needs and opportunities in key areas such as human capital, industrial development, SMEs, technology, entrepreneurship, and green investments among others,” says Al-Mashat. “We will continue to implement structural reforms aimed at increasing competitiveness, enhancing macro-fiscal resilience, and supporting Egypt’s green transition.”

Banking sector ready to help

Zekry notes that Egypt’s banking sector — one of the best run and best regulated parts of the economy — is well placed to help the authorities encourage investment and exports.

“Egyptian banks have provided tailored financial and non-financial solutions to support Egyptian exports,” he says. “Banks are designing services and initiatives to assist small and medium-sized enterprise exporters through access to credit and business support. Egyptian banks are partnering with export credit agencies to insure exporters’ products, in case foreign buyers do not fulfil payment obligations. In addition, banks are investing in digitising export-related dealings, to ease financial transactions and instantly manage exports.”

In August, CIB partnered with The Chemical and Fertilizers Export Council (CEC) to complement the country’s strategic vision of boosting Egyptian exports to $100bn.

The chemicals and fertiliser sector achieved around $8bn of exports in 2023. With about 2,000 export members, CEC is one of the largest export councils and provides vital services to Egyptian manufacturers, exporters and investors.

“The partnership hosted a series of workshops and meetings with companies and members from CIB’s staff to discuss prospective collaboration and support,” says Zekry. “Due to the bank’s strong presence in the global market, especially Kenya, CIB can provide exporters with a variety of benefits ranging from cross-border banking operations, expanding exports to Kenya’s market and East Africa’s region, and financial relations with prominent international institutions.”

CIB will also provide the council’s members with financing solutions, including short and medium-term credit facilities, documentary credit, competitive credit limits and letters of guarantee to current and new manufacturers and exporters.

“Industries operating in this sector can utilise CIB’s sustainable finance programme to reduce their carbon footprints and accelerate the transition towards a green economy,” says Zekry.

Egypt’s leading private sector bank has a history of supporting exports. In 2023, it became the Food Export Council’s official banking sponsor. Through CIB’s diverse financial offerings, the bank provided exporters with various benefits ranging between financial and non-financial services and products.

Energy expands

Cheap green power would be a boon to Egypt’s export community. The government has developed attractive investment packages to draw foreign investors into projects in green hydrogen, wind and solar power, sustainable transport, water desalination, smart cities, electric vehicles and sustainable building materials.

“They also introduced a set of incentives to bolster investment in the renewable energy sector, including tax and custom duty reliefs,” Zekry says.

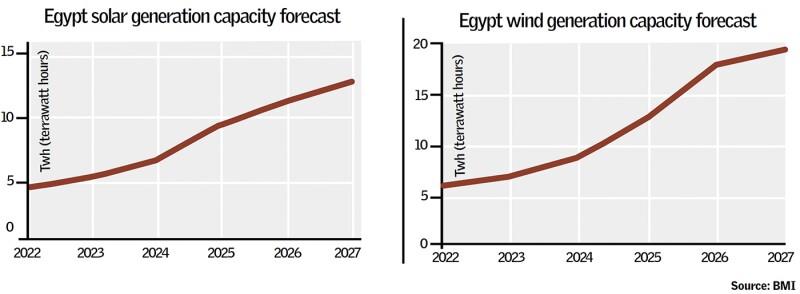

Egypt’s Integrated Sustainable Energy Strategy has set an ambitious target for its power sector of just over 40% renewable energy by 2030. This is challenging but not impossible.

BMI analysts expect a significant ramp-up of over 80% across wind and solar capacity over the next decade — providing more than 20GW of new capacity.

Egypt might be associated more with sun than wind, but at present wind provides more power. The Gulf of Suez is a windy place, and the authorities have had great success in attracting international investment.

In 2023, Maersk International signed an agreement to acquire 51% of the Zaafarana complex wind farms. Egyptian contractor Orascom Construction, Engie and Japan’s Toyota Tsusho Corp have acquired land for a 3GW wind energy project in Egypt’s West Sohag region. In May this year, it was announced that Norwegian energy firm Scatec and a consortium led by Orascom Construction had secured land for two massive wind power projects that would add 8GW and provide $9bn in FDI. That same month, flagship UAE developer Masdar, Infinity Power and Hassan Allam Utilities signed a land access agreement for a colossal 10GW mega-project — one of the largest wind farm developments in the world.

The agreement with Masdar was followed by a strategic agreement between the UAE and Egypt to add 4GW of renewable energy capacity to Egypt’s grid, starting in summer 2025. Masdar is also part of a consortium that includes UK energy group BP, which has signed an agreement with the Egyptian government to develop a multi-phase green hydrogen project.

Wind may be the main renewable source at present, but that is going to change. The Egyptian Solar Plan aims to install 3.5GW of solar power by 2027, of which two thirds will come from private investment. Well designed auctions, incentive schemes and abundant sunlight have made Egypt a highly attractive destination for solar developers.

In September, the Egyptian Electricity Holding Co signed a 25 year agreement to buy power from the country’s first solar-plus-storage project, to be built by Scatec — a 1GW solar and 200MW battery storage facility.

As with its aspiration to become a car producer for the African market, Egypt is expanding to provide power projects across the region. Egyptian multinational Elsewedy Electric is helping build the Djermaya solar PV complex in Chad.

Egypt also has significant potential to become a green energy exporter. Egypt’s grid is connected to Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Turkiye, Libya and Sudan. Initiatives with other African countries are under way, to construct new interconnectors under the Nile Basin, linking Egypt to the Eastern Africa Power Pool. Huge Egypt-Saudi and EuroAfrica interconnector projects are also being mounted.

New El Alamein city spans more than 20,000 hectares and is planned to accommodate more than 3m people by 2030. Work has begun on Phase II of the megaproject, accomodating 3 universities, 15 skyscrapers and 10,000 hotel rooms

Hope versus belief

It is relatively simple to create a positive picture of Egypt’s future. There is huge economic potential and a clear set of policy prescriptions for how to realise that potential.

The problem is that investors, company owners and business executives have seen all this play out in Egypt time and time again. Economic pressure leads to currency depreciation, then promises of reform. Currency pressure eases and investors return. Reform falters and the cycle repeats.

As one macroeconomic analyst puts it: the best guide to future behaviour is past behaviour. Egypt has a long and deeply problematic history of poor economic decision making.

Institutional investors and foreign direct investors want to be assured and reassured that there are real and true fundamental changes that will take place to create a level playing field for the private sector in Egypt. They want to see that the decisions being made are being made to create long term sustainable growth and not for short term political expediency.

Competition policy frameworks need to be improved and enhanced. There is much red tape that could be removed to help private sector businesses thrive. Trade is held back by inefficient ports and customs regulation.

There are still — to put it simply — a lot of basic improvements that need to happen for the private sector to get more involved. It is up to Egypt’s authorities to demonstrate that they can follow through and unshackle the economy. Investors have hope, but not yet belief.

“Egypt has a chance to prove that it’s on a new path, because we have been here before a number of times,” says Blair. “The new finance ministry and still relatively new central bank teams are really good and are doing the right things. But it calls for the wider authorities to prove that they can break this cycle and introduce real change.”