This desire is still not fully formulated, but the West should not underestimate its strength. It has begun to shape international affairs, such as the recent expansion of the BRICS grouping from five to 11 members, with many more countries wanting to join, and the successful G20 Summit under India’s presidency in September.

The Global South is also a banner under which developing countries are trying to coordinate their international economic policies, rendering their demands more coherent.

That would strengthen their hand in negotiating reforms, especially of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank — whose annual meetings are taking place in Africa for the first time for 50 years.

Five reforms would be particularly powerful in advancing the Global South’s cause.

First, developing countries have already helped promote the G20’s roadmap for implementing the recommendations of last year’s report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Capital Adequacy Frameworks.

The report by a panel of independent experts commissioned by the G20 argued for putting climate financing at the core of the MDBs’ missions, and called on them to optimise their balance sheets, to free up $200bn over the next decade for sustainable investments in developing and low income countries (DLICs).

Developing countries should push for these improvements to be realised, and beyond that, continue to demand an actual capital increase for the MDBs, to further expand their financing capacity. Shareholders could also expand support to the MDBs in other ways, such as guarantees or hybrid capital investments.

Give us a say

Second, the Global South must strengthen its appeal for an increase and change in the distribution of quotas and voting shares at the IMF and the Bank to better reflect its increasing weight in the global economy.

This issue is under negotiation during the IMF’s 16th General Review of Quotas, scheduled to conclude by December 15.

The previous quota reform in 2010, which came into force in 2016, increased China’s voting share at the IMF from 3.8% to 6.1%. Europe lost 1.5 percentage points, while Africa’s collective vote was reduced by 0.5 percentage points and the Middle East and Turkey’s by a similar amount. The US, meanwhile, retained veto power over key decisions at 16.5%.

This time, developing countries want more profound change, with an increase in their relative voting shares.

Several major countries such as the US and Japan have said they support a proportional increase in quotas, without change in their distribution pattern, preserving the current relative voting power.

Such a proportional quota increase may come to pass, but it will not satisfy developing countries’ demand to increase their voting shares at these institutions.

Third, many developing countries have criticised the IMF as too rigid and intrusive in using its ‘open economy, free trade’ orthodoxy to set conditions for financial assistance to members in need.

Now that countries including the US, Europe and China have used trade and investment controls and industrial policy to safeguard their national security, developing countries will press the IMF to be more flexible in its policy advice and formulation of financing conditionality.

Fourth, developing countries should try harder to challenge the presumption that the US can nominate, and effectively select, the president of the World Bank and Europe the managing director of the IMF.

When these top jobs come up for renewal later this decade, developing countries need to overcome their differences and unite behind a single credible candidate, if they hope to contest the leadership of these institutions.

Lifting the burden of debt

Last but not least, developing countries have made some small steps forward in improving the framework for sovereign debt restructuring — by launching the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable, co-chaired by the IMF, World Bank and the Presidency of the G20, and reaching a restructuring deal for Zambia.

They should maintain pressure on creditors — both official and private — to grant adequate and timely relief to highly indebted DLICs. In particular, they can discuss more seriously various ideas of debt-for-climate swaps — linking substantial debt relief to climate-related projects.

They should also press the G20, IMF and World Bank to set out a roadmap containing a sequence and timeline of steps to be taken when a debtor country applies for restructuring under the Common Framework — improving the transparency of the process.

In sum, the Global South can promote reforms of the global economic and financial system to help developing countries deal with their difficult challenges.

However, while international solidarity is important, developing countries need to recognise that they themselves are responsible for their development.

Countries unable to overcome problems of autocracy, corruption and ineptitude in their governance will be unlikely to break out of the vicious circle of underdevelopment, debt and adverse global shocks which have kept many of their people in poverty — regardless of international reforms or debt restructurings.

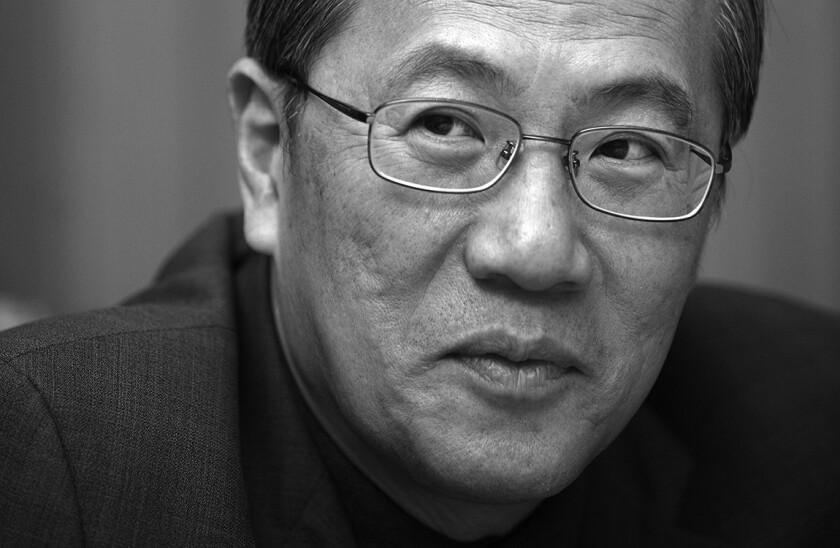

Hung Tran is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Geoeconomics Center, a former executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance and former deputy director at the International Monetary Fund