The Indian rupee has depreciated about 12% against the dollar in 2022, with pundits expecting further falls in the coming months.

That is rekindling interest in the Masala bond market — rupee deals issued outside of India. GlobalCapital Asia understands one local bond house is flooded with queries from borrowers exploring the potential to print Masala bonds.

Issuers take no FX risk when they issue Masala bonds as although they are denominated in rupees, they settle in dollars, representing a currency play for investors.

And it is amid such a currency fluctuation that the Masala market was born. The market took off in the aftermath of the 'taper tantrum' in 2013, when the threat of the US Federal Reserve unwinding quantitative easing sent markets into a tailspin. The flight of foreign investors from India's domestic market left its currency and FX reserves under pressure.

Masala bonds were designed to deepen the rupee bond market to protect borrowers from unnecessary FX swings, with the International Finance Corporation printing the first bond in the format in 2014.

The market's potential remains unlocked. According to the London Stock Exchange, where most Masala bonds are listed, $7.16bn-equivalent has been raised through Masala bonds by 13 issuers across 48 deals.

By contrast, the offshore renminbi market, which admittedly started in 2007, has about $60bn of bonds outstanding.

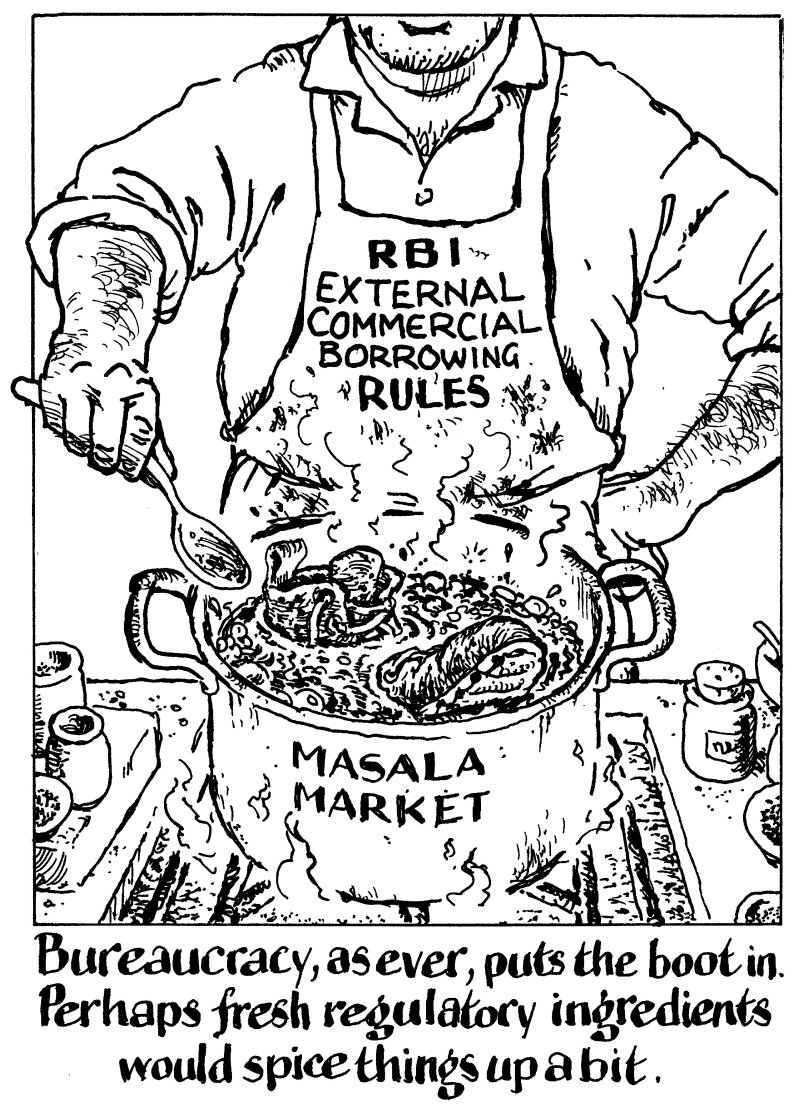

Bureaucracy is to blame. The Chinese government has taken steps to internationalise the renmimbi but Masala issuance is covered in red tape.

For instance, Masala bonds are issued under the Reserve Bank of India’s external commercial borrowing (ECB) rules which has its own set of restrictions on maturities, pricing caps and use of proceeds.

For Masala offerings exceeding $50m-equivalent, the bond maturity has to be longer than five years. Three year tenors are permitted for deals less than $50m. Such inflexibility during volatile markets is a big hurdle to clear. Global investors have been looking at shorter duration bonds than this as they try to park money.

Proceeds can be used for refinancing, working capital and affordable housing projects but the RBI prohibits the funds to be used for the purchase of land, making equity investment or on-lending.

Easing such restrictions will go a long way in attracting issuers and investors, some of which are eagerly awaiting the inclusion of India in the global benchmark indices in the coming months.

Inclusion in key global bond indices translates into FX inflows and that could help stabilise the rupee. There are also many other benefits for encouraging use of rupee outside India.

It would reduce the currency risk and put less pressure on depleting FX reserves. Less pressure on FX reserves would mean a stable currency and that also has a bearing on the ease of doing business. Indeed, Indian central bank officials have been vocal about internationalising the rupee themselves.

A thriving Masala market Masala can be a good alternative to meeting other key funding requirements. India would be able to raise billions of dollars to meet its infrastructure financing and climate change needs. Its local rupee market is not yet deep enough with most issuance still restricted to triple-A or double-A rated borrowers.

Masala bonds shouldn’t remain a mere play on the currency. With the Masala-hungry eager for deals, it is time the RBI cooked up the perfect regulatory recipe to feed them.