The Philippines has recovered the dynamism it lost in the 1970s. The economy is growing nicely, unemployment has fallen, inflation is stable, interest rates are low and the stock market is up over 70% in the last six years. What could possibly go wrong?

Well it could be the banking system if recent warnings are anything to go by. In a July report, the International Monetary Fund said it was worried about “concentration risk” in the medium term. Concentration risk is defined as ‘the probability of loss arising from heavily lopsided exposure to a particular group of counterparties’ and is markedly high in the Philippines because of the prevalence of family-controlled conglomerates.

“Any of the top five or top 10 banks probably have exposures to the top five conglomerates that is close to their single borrower limit, which is 25% of core capital,” Shanaka Jayanath Peiris, the IMF’s resident representative to the Philippines, told Asiamoney.

For public-private partnerships (PPP), which the new government of President Rodrigo Duterte is keen to harness to fund infrastructure, the single borrower limit has been upped by a further 15%.

Central bank deputy governor Nestor Espenilla went to considerable length with Asiamoney to dispel suggestions that controls on related-party lending had been relaxed. He acknowledged, however, that the conglomerate structure of Philippine banking presents special problems.

There are 17 domestic commercial banks in the Philippines and most belong to family conglomerates that control the country’s leading businesses.

BDO Unibank, by far the largest bank in the Philippines, is part of SM Group, the biggest retailer, with an empire of shopping malls, department stores and supermarkets founded by Henry Sy. Its chief rival, Bank of the Philippine Islands, is part of the Ayala family conglomerate that is the country’s biggest landowner. The jewel in the Ayala crown is their Makati estate, acquired in 1851 and home to the country’s financial hub.

Other conglomerates centred on banks have extensive interests in power supply, telecoms, food and agriculture, property, insurance, hotels, automobiles and airlines.

“When a family makes a killing in one business, chances are eventually they would like to own a bank. There’s great prestige in owning a bank in the Philippines. You’ve arrived if you own a bank here,” Alfred Dy, head of Philippine research at CLSA, told Asiamoney.

“Traditionally, banking has been profitable in the Philippines. Even now the ROEs are probably north of 10%. They used to be much higher. Then there are a lot of synergies. While there are very strict lending rules, in terms of deposit generation there are no limits.

“If I am a big conglomerate and own a bank, I could do a lot of cross-selling within the group and among the clients. So you could do a lot provided you don’t abuse the lending side.”

Buying spree

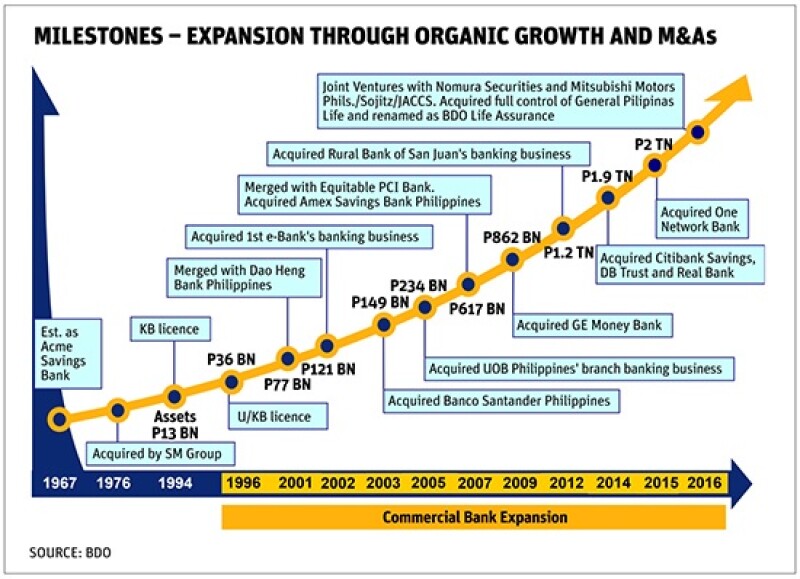

BDO started life as a tiny savings bank that Henry Sy took over in 1976 and renamed Banco de Oro. When Eduardo Francisco, president of BDO Capital, joined the bank in 1999 there were just 108 branches; now there are 1,057. This phenomenal expansion, in which assets have risen by 26 times, has been turbocharged by acquisitions. Ever since a 2001 merger with Dao Heng Bank Philippines, BDO has maintained a full-time team for M&A and banking integration. During that time, BDO has swallowed a string of local operations of foreign banks, usually as they sell up and exit the Philippines having failed to crack the consumer market.

By far BDO’s biggest grab was in 2006 of Equitable PCI Bank, the third-largest bank by assets in the Philippines. The most recent was of One Network Bank, the largest rural bank in the Philippines with more than 100 branches. One Network is based in southern Davao, the home city of Duterte.

And this June, BDO sold 40% of One Network to TPG Growth, an American private equity firm with a track record in microfinance. It is the first time Francisco can recall BDO selling off part of an acquisition.

With over 600 banks remaining, the industry would appear ripe for further consolidation. However, the vast majority are small community banks in which big players have little interest.

“Until recently, the central bank would not grant new branch licences, so the only way you could expand your branch network, which is the key to getting more deposits, and therefore to lend more, was to acquire banks,” Francisco told Asiamoney. “So we were willing to look at their balance sheet and non-performing loans just to get branches.

“Now it is easier to buy a branch licence than to do due diligence on a small bank that may have only three branches. It is too much headache for us. So I think consolidation is slowing down.”

The last of the top banks up for sale for sale was government-owned United Coconut Planters Bank. BDO was one of 12 local and foreign banks to have expressed an interest, but when they examined the books, “the hole was so big it was not worth bidding for it any more. If they split it into a good bank and a bad bank, I am sure we would be interested.”

Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ was another of the 12 potential bidders. Earlier this year, BTMU bought 20% of mid-tier Security Bank Philippines for Ps36.9bn ($793m). This represented a 69% premium to the share price, according to CLSA’s Dy.

Besides astute acquisitions, there is another, more contentious factor in BDO’s success. SM Investments, which holds a majority stake in BDO, and wholly owns its sister China Banking Corporation catering to the ethnic Chinese community, also owns 314 department stores and supermarkets, as well as 58 shopping malls. Another arm is a leading developer of commercial, residential, hotel and resort properties.

As BDO advertises in its investor presentation, this gives the bank invaluable access to SM’s customer network of “over 17,000 tenants” and “more than 9,500 suppliers”, as well as branch and ATM locations inside SM malls, “home mortgage financing for SM property projects,” SM expertise in retail, property and the middle market and last but not least, “goodwill from the SM franchise.”

Such close ties bother Alka Anbarasu of Moody’s Investors Service. “This conglomerate nature of banking ownership is something unique to the Philippines, and from our perspective we are always a bit concerned about the interconnectedness,” she told Asiamoney.

Teresita Sy, eldest granddaughter of the founder, chairs BDO’s board, although there are now four independent directors.

“Most of the seniors in the bank are professionals but the family are very involved at the board level, and we seek approval from them, particularly for strategy and directions,” Francisco said. “They trust us to run the banking side, but we keep on reporting to them. We already know what is important to them.”

BPI, the Ayala bank, declined to make anyone available for interview because this article was also going to feature BDO.

The IMF’s Peiris predicts “very gradual change” to the conglomerates, noting that “no one has changed the regulations on ownership.” Still, he is impressed by a new Philippine competition law and watchdog. “They are taking their job quite seriously. The legal framework is relatively strong compared to that of some ASEAN countries.”

One wildcard is the plan approved last year for ASEAN banking integration, of which a key component is designation of a Qualified ASEAN Bank (QAB) entitled to similar treatment as local banks in other ASEAN markets.

Some ASEAN banks, such as Maybank and CIMB, already have branches across ASEAN, and Maybank has been expanding aggressively in the Philippines.

"The Philippines is feeling peer pressure from this ASEAN process. One of the reasons why the Philippines has opened its banking market to the whole world is to have strong partners from outside ASEAN in order to compete against banks from their ASEAN neighbours,” Noritaka Akamatsu, an expert on Asian finance at the Asian Development Bank, told Asiamoney.

"One thing Philippine banks are trying to do is to become bigger. That will require capital, so partnering with a major foreign bank like BTMU would be one way. It diversifies ownership and makes the bank less reliant on its conglomerate group,” Akamatsu explained.

Partnership rather than outright ownership makes more sense to a non-southeast Asian bank because of the QAB discrimination. “If a non-ASEAN acquirer, such as BTMU, gains majority control of a bank here in the Philippines, it would no longer be considered a Philippine bank. It would be considered a Japanese bank. Then it would not be eligible for QAB status, and for the ASEAN banking passport that provides."

The Philippine government and central bank have difficulties of their own in negotiating QAB with Malaysia. Philippine banks are embarrassingly reluctant to take advantage of QAB to expand elsewhere in the region.

“Why would a Philippine bank want to go to a more competitive market where profit margins are thinner, while they have a very lucrative market at home?" Akamatsu pointed out.

The view from the regulator

Is it a concern that so many of the Philippine’s largest banks belong to non-financial conglomerates? This is not only an aberration in the Philippines. It seems to be not uncommon in Asia. Our law today, as it stands, does not prohibit this kind of arrangement. However, we recognise that there are risks that we are mindful about as a bank regulator and we have implemented a whole range of regulations that govern the nature of relationships between related parties. We have what we consider to be sufficiently prudent related-party transactions rules. There are still more than 600 banks in the Philippines yet it seems that consolidation has slowed. We have today 610 banks, and that includes 513 that are small community banks. The combined total assets of all of the 513 is only about 2% of the total banking system. That’s how tiny these are. Now, among the 610 banks we have 41 universal and commercial banks, and most of these are foreign bank branches. Only 17 are domestic commercial banks. [The ban on opening new branches] was meant to consolidate the community banks, since they were subscale and very challenging to supervise. So BSP actively encouraged their consolidation, which continues to happen. The BSP’s approach is not to mandate the marriage of entities, but to let these things be driven by the market, strategic considerations, regulatory pressure and competition. Are you in favour of mergers among the larger banks? We would be glad to see it if is a reflection of a strategic decision. The strategic considerations could again be in response to competition and opportunities, especially since we are part of the ASEAN community. There will come a time when our banks decide it is strategically in their best interest to combine, and become more competitive. Does the BSP no longer seek to protect Philippine banks from foreign competition? Our liberal foreign bank entry law of 2014 basically allows full entry of foreign banks that are of good quality. The only control left is the limit of 40% for the total assets of foreign banks in the Philippines, but that is not a binding constraint because today that total is only around 14%. So there is a lot of room for additional players. Foreign banks appear to have given up trying to establish retail businesses in the Philippines. Domestic banks have proven themselves to be quite competitive in the retail space. The foreign banks have mostly withdrawn or sold off their retail businesses. We now have nine foreign banks, mostly branches, that service niche markets. They focus on investment banking, institutional banking and also advisory business. Do you believe that more investment by foreign banks will help the local banking industry? We encourage our banks to consider strategic partnerships with foreign banks as part of their growth strategy. A recent example is Security Bank, a middle-tier universal bank in the Philippines, taking on a strategic investment by BTMU. Such arrangements do a couple of things. One is it injects additional capital that allows a domestic bank to gain bigger scale more quickly. Secondly, we are of the view that the entry of major banks as strategic investors in a local bank can improve corporate governance, and in a way dilute the influence of conglomerate structures, since there are now other pairs of eyes looking into the activities of a bank. We come back to the issue of conglomerates and family control. Yes, it is allowed by law, but as a regulator it is a risk area that we are extremely conscious about, which is why we have prudential regulations and corporate governance-related regulations to try to manage the risk. Part of that management is to allow strategic foreign investors into the bank so that the relationships can be more diluted and therefore be even more arm’s length. So it helps the regulatory environment that we have this kind of strategic partnership. There is a third angle. We think that strategic foreign investment can also bring improved knowhow, whether that be in digital technology, in organisation or in marketing contacts. That also improves the competitiveness of banks. Such as BDO’s sale of 40% of One Network Bank to this American private equity firm? BDO says it gives them access to superior American knowhow, especially in fintech, while others claim it just shows that BDO’s capital is stretched. The first explanation makes sense, at least to us. One Network Bank is but a rural bank subsidiary of BDO, and it basically just gave up 40%, not control, of that rural bank subsidiary, although it happens to be the biggest rural bank in the Philippines. The way they explain it is they are developing a target market, so they don’t want to use their flagship brand, BDO, because it is already an established player at the institutional and high-end market. Certainly if you look at the Philippine financial environment today there are a lot of unbanked communities, and the vehicle for trying to target that market is through their subsidiary which they are now tapping through a partnership with someone they have identified to have knowledge ... In microfinance... Right, in Indonesia. This is an example of what I am saying. They are bringing in knowhow that they feel they don’t have and quickly ramping up their operations, so it is a progressive move. Is not the goal of PE to improve performance, then bring the company to market and exit with a large profit? That’s the nature of private equity. If it results in a better organisation, then I guess it’s natural there is a market reward. |

All in the family

“In essence, the Philippines is a family conglomerate-controlled based economy, and that characteristic is not easily going to go away,” said Shanaka Jayanath Peiris of the IMF.

And at the heart of each family conglomerate sits a bank ...

BDO Unibank: The Philippines largest bank by assets, loans, deposits and AUM is 54% owned by SM Investments, holding company for the family of Henry Sy. His daughter Teresita is chairperson of BDO. China Banking Corporation, ranked 6th in terms of assets, loans and deposits and 4th for AUM, is 100% owned by SM. Retailing magnate Sy is the richest man in the Philippines.

Bank of the Philippine Islands: The oldest bank in the Philippines and 2nd in size of loans, deposits and AUM. Ayala family interests own 48.3% of BPI and 8.3% is held by the Roman Catholic archbishop of Manila. Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala is chairman of BPI and his brother is vice chairman. Ayala Land owns 950 hectares of Makati and is the largest property developer in the Philippines.

Metropolitan Bank & Trust: Ranked 2nd by assets and 3rd by loans, deposits and AUM, Metrobank is majority owned by the family of its founder, George SK Ty. The chairman, Arthur Ty, is his eldest son, while director Alfred Ty is Arthur’s brother. GT Capital, the family conglomerate, also has interests in property, power generation, insurance and automobile assembly, import, distribution and financing.

Philippine National Bank: Formerly state-owned, PNB was taken over by a group of shareholders led by Lucio Tan in 2000. It is the 5th largest bank by assets, loans and deposits, and 6th by AUM. As of last year, 78.97% of PNB was held either by the Lucio Tan Group, by Lucio Tan himself or his associates. Tan and two other members of his family sit on the board of PNB, one of the weakest of the major Philippine banks and often cited as a possible M&A target. The Lucio Tan Group also controls Philippine Airlines, the national flag carrier, of which Tan is chairman and CEO.

Rizal Commercial Banking Corp: A flagship of the Yuchengco Group, one of the oldest conglomerates in the Philippines, RCBC is the 8th largest bank by assets and deposits, 7th in customer loans and 5th in AUM. The Yuchengco empire began when Yu Taio Qui and his son Yu Cheng migrated to Manila from their home in Fujian province. Taiwan’s Cathay Life Insurance also owns 22.71% of RCBC.

Union Bank of the Philippines: The Philippines’ 9th largest bank by loans and deposits is majority owned by Aboitiz Equity Ventures, the conglomerate of the Aboitiz family. Like the Ayala clan, the Aboitiz originated in the Basque region of Spain; patriarch Paulino Aboitiz, a Basque mariner, landed in the Philippines in 1870. Aboitiz interests span power generation and distribution, finance, food and agriculture, property and construction. An Aboitiz is vice chairman of Union Bank and three other family members are directors.

East West Banking Corp: East West is part of the Filinvest conglomerate which also has interests in property, sugar, hotels and power generation. Almost 90% of Filinvest is owned by the holding company of Andrew Gotianun, a Chinese-Filipino who began by salvaging ships at the end of WWII. Gotianun’s son is chairman of East West and his wife and daughter are directors.

Robinsons Bank: John Gokongwei is the second-richest entrepreneur in the Philippines, after Henry Sy. His JG Summit conglomerate wholly owns Robinsons Bank, which in 2010 bought the Philippine business of Royal Bank of Scotland. Gokongwei’s other businesses include food and beverage companies, a budget airline, property development, petrochemicals, telecoms and electricity distribution. He is a distant cousin of Andrew Gotianun.