Phenomenal, fast-growing, exciting. These are just some of the words market watchers are using to describe the development of the green bond market in Asia. And if the numbers this year are anything to go by, they are not wrong in their thinking.

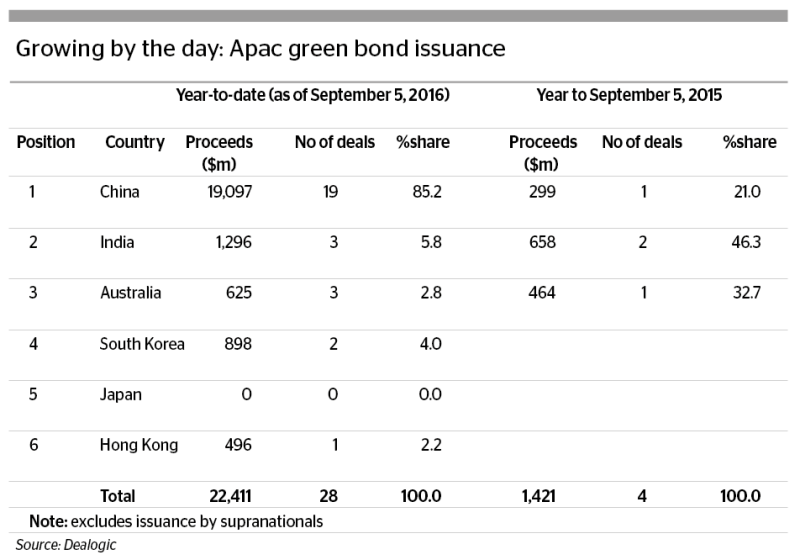

According to Dealogic, 28 green bonds have been sold in Asia Pacific this year as of September 5, 2016 — a colossal jump from the four sold during the same time in 2015. In volume terms, the numbers have risen from $1.42bn to a whopping $22.4bn.

At the heart of this growth are China and India. China accounted for $19.09bn of volumes so far in 2016, with India ranking second with $1.29bn of deals. And more green notes are widely expected from both the countries before the year is out.

“China is by far the largest regional influence on this market with India potentially matching it over time,” says Ricardo Zemella, managing director, head of DCM and syndicate for Asia at ING Bank in Singapore. “Overall, Asia’s relative high growth and need for infrastructure make the region fertile ground for green financing.”

The green market received a big fillip in early September at a meeting of the G20 members in China — an event where the most populous country in the world made the fight against climate change its core agenda. On September 4, the US and China outlined plans to expand their efforts on climate change, including formally adopting the international climate change agreement reached in Paris in December 2015, COP 21.

Bankers reckon the agreement will encourage other nations to also formally adopt the Paris pact and work towards making the environment cleaner and more sustainable — eventually leading to the sale of more green debt across the globe. But whether Asian countries will be eager to rush in remains a question.

“There are still a number of relatively poor Asian economies where many people live from one day to the other and sustainability does not score high on their priority list,” says Martin Wehling, head of debt origination for Asia Pacific at DZ Bank in Singapore. “So there are various government initiatives to push a sustainable economy and sustainable usage of resources. However, we do see a lot of changes among Asian market participants over the last 18 months, from governments, regulators, exchanges, issuers and investors alike.

Top down

Asian countries generally have taken a top-down approach to developing the green market. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) in December 2015 laid out guidelines for green debt issuance by financial institutions. At the end of last year, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), released guidelines for corporate issuance of green bonds.

India too has taken conscious steps, having set itself an ambitious objective of building 175 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity by 2022, requiring an estimated $200bn in funding. To that effect, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) put together a green bond framework in January 2016 following a public consultation.

Both countries have seen a mix of domestic and international issuance. In China, the first mover was Shanghai Pudong Development Bank, which sold a Rmb20bn ($4.3bn) onshore bond in January. Offshore, Bank of China sealed a landmark $3bn green deal in July, which was at the time the fifth largest green issuance globally and Asia’s largest international green trade.

India, meanwhile, saw the first onshore issuance from Yes Bank in February 2015. The maiden international bond, meanwhile, came from the Export-Import Bank of India (Exim Bank), which blazed the trail for other financial and corporate names to follow.

South Korea too has seen a fair bit of action this year, having seen no green issuance in 2015. The Export-Import Bank of Korea (Kexim) returned to the green market in February, having been Asia’s first green issuer in 2013. It was followed by Hyundai Capital Services this March with a $500m deal. The Japanese market, however, which last year saw two green notes worth $839m, had recorded no deals as of September 5.

The fact that a chunk of issuance has been from names in the financial sector or from policy lenders has not gone unnoticed.

“This is a normal trend and was the way the green bond market also developed in Europe,” says Wai-Shin Chan, HSBC’s Asia Pacific director for climate change strategy, based in Hong Kong. “For corporates, it is good to have a list of projects they can fund that is green. Given knowledge about green bonds is still not very high, it is easier to sell a green bond from a very credible financial institutions, rather than a corporate that people may not know.”

Elusive benefits

That’s not to say the market has not welcomed some corporates. Hong Kong’s Link Reit, China’s Zhejiang Geely Holding Group and AboitizPower Renewables from Philippines have sold green debt. In India, the likes of Greenko Power have laid the foundation for corporates.

“The green concept is relatively new for south Asia, but we are seeing lots of interest from corporates with enquiries on the format, the assets to be applied etc,” says Shyam Saraf, vice-president, capital markets group for south Asia at MUFG. “So going forward we could see a surge in issuance.”

One of the biggest challenges holding back issuance is pricing, say market watchers. On the primary front, issuers have typically sold green debt in line with their traditional bonds, driven by a couple of factors.

For starters, the majority of the Asian issuers sell their notes in Reg S format. But most of the green dedicated investors are in Europe and the US. With US accounts already shut out, that leaves European green investors. But given their assets are typically in euros, their involvement in dollar deals tends to be limited, say bankers. As a result, there is little price tension to prove beneficial to issuers.

“The benefits of pursuing a green bond remain elusive from a strict pricing perspective,” says ING’s Zemella. “A bond issuer embarking on such a path derives value from the signal it provides the market: they are investing their time and efforts in embracing sustainable financing standards and doing ‘the right thing’ towards the environment. Pricing benefits will come with time as the asset class develops and standards become more consistent across geographies.”

Under pressure

Frank Kwong, head of primary markets, Asia Pacific, at BNP Paribas in Hong Kong says he is seeing a shift to project bonds and renewable power as companies transition from using coal to cleaner energy.

“Philippines is a growth market where there will be development bank and private capital involvement to finance such projects, and this can be done using green bonds. So we are expecting a lot more supply,” he says. “We’ve been pitching green bonds to issuers as we feel that the timing is right and it makes sense to finance projects using green bonds. A lot of Asian issuers have CSR objectives which can involve green investors.”

Vicky Münzer-Jones, a Singapore-based partner at law firm Norton Rose Fulbright, reckons the interest in selling green debt — despite no pricing advantage — stems in part from a fear factor of being left behind.

“There is anecdotal evidence that there is a deeper market for green bonds; you may not be able to put a price on it, but there is a bigger pool of investors to tap and that’s the way the market is going to move,” she says.

It has not been easy to get here however and the way forward will also be a challenge. Putting the framework into place was something the market had been working on for years. And even now, the main challenge is the different approaches and thinking behind what is green and what is not.

Here, parties like the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) have come into play with the body putting together guidelines for green bonds.

ICMA’s guidelines focus on transparency and accountability, according to its Hong Kong based Asia Pacific chief representative Mushtaq Kapasi.

He says that it is about the right reporting disclosure standards and then the body gives the market the freedom and flexibility to decide how green a product it wishes to buy.

“The market is now at a stage where either issues have been ironed out or people agree to disagree about having different standards,” he adds. “And that is healthy — so long as we’re adhering to the principles, it’s up to the market to accept or not accept whether something is sufficiently green or not.”

Different shades of green

That is why the concept of getting independent third party verifiers for green bonds has gathered momentum. Meanwhile, the number of UK verifiers is growing and there is now increased competition with numerous verifiers aggressively pitching to issuers.

“There is some concern in Asia about the shades of green as there is fear that the process of getting a green tick is too easy,” says Westpac’s head of DCM and syndicate, Asia, Russell Baines. “Products may be labelled green but it raises a question of how sustainable the use of funds actually is. Feeding back into the requirement for a deeper market to get to a self-sustaining size — the hope is that the market doesn’t branch off into a little bit of green, very green etc. as we see growth in issuance.”

There is help at hand, however. Sweden’s SEB Bank and Germany’s GIZ have a strategic alliance to educate those in the green industry. Their partners in Asia include India and China.

“At the heart of the alliance is the idea that we want to provide a lot of knowledge and transfer the profound expertise our partner SEB has through technical workshops offered to key public and private stakeholders in our partner countries,” says Yannick Motz, who manages the emerging markets dialogue on green finance at GIZ in Eschborn.

This might well serve the Asian market, which still has numerous challenges to overcome if wants to grow further. The absence of green dedicated investors is a big hurdle, but is also one that is unlikely to be remedied in the near future. This is because the green bond market in Asia is caught in a chicken or egg situation — green investors will set up shop if there is more critical mass in the market but the mass can only be reached with more buy‑side activity.

“The main tangible benefits of green bonds are not in enhanced seniority or security but the use of the proceeds and transparency via additional reporting,” says Alex Struc, an executive vice-president and portfolio manager at Pimco in London. “While investment grade companies can just borrow for general corporate purposes, green bonds with specialised annual reporting offer additional transparency on how the proceeds are used.”

But Pimco has a strict policy when it comes to investing in green debt.

“Buying green bonds just because they are green is not a prudent choice,” added Struc, who also co-heads Pimco’s ESG effort. “If the cheapest to deliver happens to be other than green debts of the issuer we like, we will buy the non-green bonds and still engage with the issuer to get a better understanding of their social and sustainable footprint.”

Educating investors

The Hong Kong debt market got a boost in July with Link Reit becoming not just the first green issuer from the city, but also the first property developer to go green. The path to its trade was a long one, with the issuer first holding investor meetings in July 2015 but delaying its deal due to volatility.

“Capital markets conditions change every day,” says Hubert Chak, Link Reit’s director of finance in Hong Kong. “After Brexit and the market reaction, and then the Fed meetings minutes, it led to a situation where 10 year [US] Treasuries were at historical lows so we started to look at the market closely. Our objective was to get low cost, green bond investors and push out the overall maturity of our debt portfolio.”

Doing a green bond was something suggested by bankers close to the issuer as a way to finding a new investor pool. In addition, as a Reit, the issuer had stable income — something investors liked.

“We faced two challenges,” says Chak. “One was with educating investors. Some investors had already invested in Hong Kong and Asia and part of their mandate is to invest in companies that take efforts in sustainability — these were the light green bond investors.

“And then we had ‘dark green’, or dedicated, investors that only buy green bonds and have a check box for what is green and what is not. They are very strict on what they can invest in but they are not familiar with Asian companies. So in July 2015 and 2016 we had to educate them on our background and history.”

Its debut green outing stemmed from the fact that Link put together a sustainable framework about five or six years ago as a way to think about the community and its stakeholders.

Chak adds that there was no benefit on issuing a green bond from pricing perspective, but there was no disadvantage either. The company had to incur some documentation cost, but Chak says it was quite “immaterial” considering the amount raised.

“For companies looking to issue green bonds, it is really important to start planning early. I’m not saying that we are very forward thinking, but companies should take efforts on sustainability and energy saving, as ways to manage your projects well. It’s not something you can do within months; it’s a long-term commitment.”

It was this focus on sustainability that drove National Australia Bank (NAB) to become the first green bond issuer from Australia in 2014, selling a $300m deal.

Its head of capital financing for Asia, John Barry, says: “We attracted new to NAB debt investors and SRI investors, were able to extend the tenor of our funding mix by issuing a seven year green bond and managed to highlight our commitment to financing the transition to a low carbon economy.

“Since our inaugural deal, the Australian green bond market has continued to evolve, attracting new issuers, new investors and new green bond formats so it’s good to know that we had a role to play pioneering the development of the green bond market.”

Doing a green bond was in line with the bank’s broader ESG credentials. In 2010 NAB became the first Australian bank to be certified as carbon neutral. And in 2015 it committed to undertake low carbon financing activities of A$18bn ($13.52bn) over seven years.