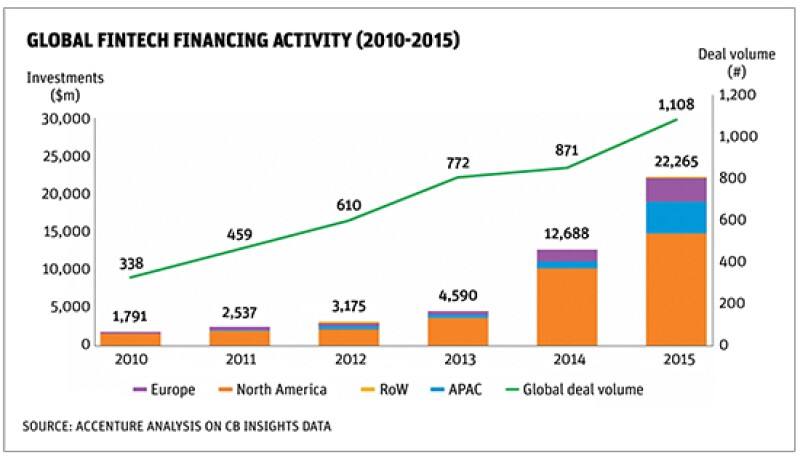

Fintech, or financial technology, has been relatively slow to gain momentum in Asia but is now seeing its moment in the sun. In a report earlier this year, consulting firm Accenture found that fintech investment in Asia more than quadrupled in 2015 to $4.3bn. During the first quarter of 2016, fintech investment in the region rose 517% making Asia the second largest region worldwide for investment into financial technology.

For the region’s banks, the surge in interest is something of a doubled edged sword. In a survey, PricewaterhouseCoopers found that 81% of banking chief executives are concerned by the pace of technological change and 70% of leaders in the industry feel the same way. Some are partnering and investing in fintech startups while others are trying to create innovation incubators internally.

“Although fintech is a global phenomenon, the impact has arguably been greatest in Asia, especially because of the scale,” said Zennon Kapron, a director at research and advisory firm Kapronasia in Shanghai.

Ripe for the picking

Nowhere has fintech’s impact been greater than in the retail consumer market. A dearth of payment options for consumers and the ubiquity of mobile internet, smartphones and e-commerce created an environment ripe for innovation.

In China, limited credit card use pushed consumers toward alternative payment systems and technology companies stepped in to fill the void. Alibaba-backed Alipay has been operating for 12 years and has become the country’s dominant provider controlling roughly half of China’s online payments market.

“Banks in China haven’t done a particularly good job [at targeting the middle class] as their focus has been elsewhere,” said Mark Young, head of Asia Pacific financial institutions group at Fitch in Singapore.

In India, where nearly half of the population does not have a bank account, firms such as One97 Communication and Freecharge are making it easy for consumers to pay for goods or for services like ordering food while firms such as Capital Float are providing an alternative source of small business loans. ASEAN countries, where banks are similarly underpenetrated, are also becoming a hotbed of fintech startup activity.

Overseas competition

Not that all the activity is homegrown. As fintech markets in Europe and the US mature, firms from those regions are eyeing Asia and its financial centres as attractive hubs for growth. In the last 12 months, a wave of fintech companies from Europe and the US have been opening up in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Recent moves into the region include Chicago-based digital payment platform Braintree which launched in Australia, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore last year. Meanwhile Dutch payments technology company, Adyen, hired PayPal’s former head of core payments for Asia Pacific, Warren Hayashi, to spearhead its expansion efforts in the region.

“The fairly advanced technology coming from the West, that is not really available here yet, will impact the financial institutions, enhance systems and improve processes” said Markus Gnirck, partner and co-founder at Tryb, a private equity investment partnership in Singapore focused on fintech.

Companies like bloq, figo and SETL, which have been successfully transforming the middle- and back-end of banks, are only just starting to enter Asia. In certain sectors such as asset management, trade finance and capital markets, more advanced business-to-business solutions have yet to mature. Analytics and security as well as new enterprise-grade platforms, such as machine learning, cognitive computing and artificial intelligence, are all underrepresented in Asia, said Tryb.

Despite their technological advantage, competition will be tough for new entrants. Foreign startups will be going up against regional and local incumbents such as Alipay, WeChat Pay, Paytm, Samsung Pay plus global giants such as Apple Pay. Regional behemoths such as Alibaba are already showing they have ambitions far beyond their own home countries. Ant Financial, an affiliate of Alibaba, said in June it would buy a 20% stake in Ascend Money, a new Thai financial services company owned by a subsidiary of conglomerate True Corp.

Banks partner up

Not to be outdone, banks have been formulating different strategies on how to deal with the wave of fintech challengers. For many of the larger banks, that has meant investing, collaborating or partnering with those firms. Some banks have also started incubators, complete with Silicon Valley-style names, in the hope of spurring innovation in-house.

For example, in March this year Standard Chartered launched the eXellerator in Singapore, an innovation lab that works with business units in the bank to explore the use of emerging technology and data science. The bank also added mobile payments system Apple Pay to its platform in May. In addition, it worked with DBS and Singapore’s Infocomm Development Authority to create a distributed ledge technology application that enhances the security of trade finance invoicing and helps to reduce duplicate invoice financing. “Fintech firms and banks actually can have a symbiotic relationship,” said Goh Beng Kim, head of transaction banking in Singapore for Standard Chartered.

Another bank investing in emerging technology is DBS, which has run its Accelerator programme in Hong Kong for the second year in a row with venture capital firm Nest. Fintech startups in the programme get funding, mentoring and networking opportunities. Employees also have opportunities to work with companies in hackathons and can pitch business ideas to DBS HotSpot, a ‘pre-Accelerator’ programme for digital startups. DBS HotSpot gives an award of S$25,000 ($18,663) and doesn’t take equity. To date, DBS has invested S$200m in fintech over three years, that’s in addition to the S$1bn that the bank has invested in strategic technology initiatives.

And it not just Singaporean banks that are taking a lead. Kuala Lumpur-headquartered CIMB started an incubator a couple years ago to fund and collaborate with fintech startups. The bank has already backed a number of companies that will launch products, either separately or as part of CIMB’s platform.

Lucas Chew, managing director of cash management and transaction banking at CIMB, emphasised that new technology helps banks be more cost efficient. The bank has been working with two fintech firms on an end-to-end cash management service that combines a point-of-sale solution, payments gateway site and accounting software. The new service is expected to come out at the end of this year or early next year.

“There is a lot of space for collaboration. They [fintech companies] can actually help us get to where we want to be while banks can back the platform that can actually allow the customer to be serviced,” Chew said.

For banks, accelerator or incubator programmes are an attractive way to source and buy new technology to increase competitiveness. “There are an infinite number of existing problems in banking as an industry that we haven't yet solved,” said Neal Cross, chief innovation officer at DBS. “We've created DBS Accelerator in the hopes that we may be able to solve some of these problems, as well as drive culture change within the bank. Bankers need to learn from these startups,”

Cross added that it’s “not simply about creating more revenue. We must also adapt ourselves. Banks and financial institutions that don't adapt will not survive.”

Looming large is the threat from internet giants such as Alibaba or Tencent.

“These companies have already acquired a massive customer base and have the platforms through which they can engage customers and test, experiment and deliver new banking services,” Cross pointed out. It makes sense to partner with fintech startups, he said, because startups face more challenges growing their customer base.

Banks have the capacity to deal with infrastructure and regulatory licensing as well as the brand, expertise, customer base, geographic spread and customer trust. In a recent study, consulting firm Accenture found that 86% of customers in North America trust banks over all other institutions to manage their personal data. Clearly, fintech firms need to build on their relationship with consumers. Partnering with banks is one way to gain that trust and attract customers. However, fintech firms need to decide what type of partnership they want to have with a bank.

“You have to be very clear in your mind whether you are an open system or one bank solution,” said Mukesh Bubna, founder and chief executive of Monexo, a peer-to-peer lender in Hong Kong. “If you become one bank solution, it’s like being tech provider to one bank. You’re not changing anything, just enabling the bank to be more efficient.” Monexo was one of several firms that were part of DBS Accelerator programme last year.

Bubna sees two types of banks: those with a venture capital arm and those with accelerator programmes. Venture capital arms, such the one owned by Citi called Citi Ventures, are not only looking to invest in technology that can be brought into the bank, they’re also open to technology that can be scaled up and expanded across the industry. Then there are banks with accelerator programmes that are just looking to buy a solution that can make their business more efficient.

Despite the potential downsides, more accelerators and partnerships between banks and fintech companies are sure to come. If banks don’t do anything, there’s a real risk that they could lose their engagement with customers, becoming just a commoditised ‘core’ for financial services, Cross said.

“The new competition is good for our industry and will ultimately help us to deliver a better service to our customers. Startups need banks. Many of them seek to sell their fintech solutions to existing players. Banks also need startups.”

Regulators play catch up

Banks sometimes say that fintech companies have an advantage because they don’t have to deal with as much regulatory red tape. But as the industry grows, regulators are looking more closely at the industry. Regulators, like banks, are playing a game of catch-up.

Mobile wallets, contactless payments and peer-to-peer payments have been in existence for a decade already. And yet, in Asia, there are no directly applicable regulations. Now a second wave of more sophisticated fintech innovation is coming to the market – blockchain, peer-to-peer insurance and cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

“Regulators have their hands full with the old processes and now they are suddenly seeing new things coming up very rapidly across the financial sector. So they are grappling with all of them,” said Monexo’s Bubna.

When Monexo launched in Hong Kong last year, the company ended up adopting the guidelines of the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) because there were no regulations in Hong Kong.

“Regulatory clarity is very important from an organisation point of view and customer point of view, said Bubna. “At the same time, there was no regulatory clarity on peer-to-peer lending in the UK from 2005 to 2014 and yet at the same time the lack of regulations did not stop people from doing things. It’s all about self-regulation; how you do business.”

But in an encouraging sign, he and other industry insiders said that Asian regulators are being proactive.

Following in the footsteps of the UK’s FCA, which opened a ‘regulatory sandbox’ in May this year, the Monetary Authority of Singapore in June introduced a proposal to start its own sandbox. Under the proposal, applicants – both banks and fintech firms – can apply to be part of the scheme and experiment with new technology under relaxed regulatory requirements if needed. The sandbox gives firms a chance to test out technology that might otherwise be stunted by regulatory uncertainty.

“The sandbox will help reduce regulatory friction and provide a safer environment for fintech experiments. We believe this will give innovations a better chance to take root,” Jacqueline Loh, deputy managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore said in a statement at the time.

Meanwhile, the Reserve Bank of India has started looking into how to deal with the unregulated peer-to-peer lending business. In a discussion paper from April, the banking regulator said it sees a role for this type of lending but that “it would be prudent to regulate the emerging industry” because it has the “potential to disrupt the financial sector and throw surprises.”

“It’s better to think of these things proactively and work with the industry to help pave the way. Being proactive means enabling entrepreneurship without the fear of law,” said Bubna.

And in Hong Kong, the government has set up a steering group including several government and regulatory officials as well as business executives and researchers to advise how the city can become a fintech hub. The group is tasked with assessing the economic and business opportunities to be gained by developing fintech in Hong Kong.

Regulators will also be looking out for the best interests of their domestic industries. In Thailand, the government has regulated the use of Tencent’s WeChat Pay, which has become a popular payment option in the country. Specifically, the Central Bank of Thailand issued warnings to domestic merchants to be careful using foreign online payment systems in order to avoid security risks.

The region’s various regulatory agencies face a tricky task balancing the need for new technology with new operational risks.

For banks, the new technology offers a chance to serve clients more efficiently in greater numbers while also reducing costs. The challenge will be staying ahead of their more nimble fintech rivals while meeting regulator demands and avoiding compromising customer safety.