Private and investment banks in firms which have both have traditionally existed independent of, and sometimes despite each other, given the deep differences in culture and competition for clientele.

Those differences are fading as banks pivot to becoming a so-called ‘one bank’, an approach characterised by a desire to increase the share of wallet from clients and further entrench them into the bank.

In the past, issues such as deal size were a stumbling block, said Josie Ling, head of private wealth management at recruiter Eban. Because investment banking fees are tied to the size of a deal, bankers were reluctant to share their resources with the private bank, where trades are often smaller or less profitable than with institutional clients.

Transactions of less than $150m, for example, may not make sense from a cost and resources perspective for investment banks, said Rahul Sen, head of private wealth management at search firm The Omerta Group.

Culture also plays a part. For private bankers, the client relationship, nurtured over years or decades, is paramount. Investment banks, however, see clients primarily as a source of transactions.

Those notions are being upended as investment banks, squeezed by regulation and competitive pressure, but equally enthralled by the opportunity to generate business from their wealth divisions, look toward private banks. The Swiss banks have been at the forefront of this trend, though they are hardly alone in embracing it.

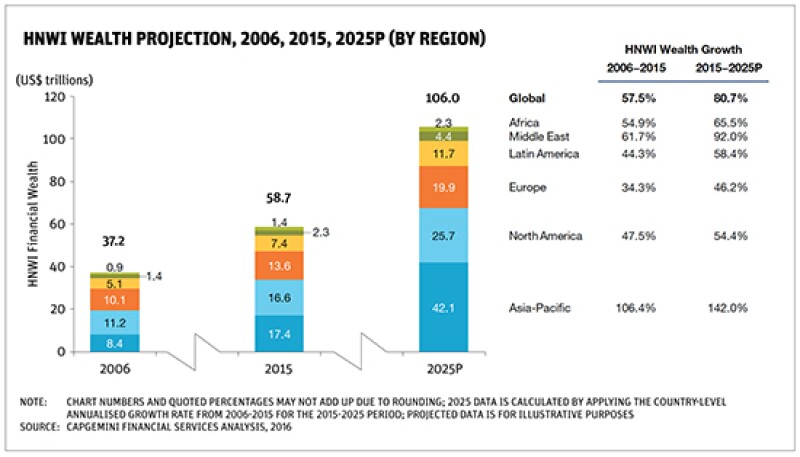

And banks would be remiss not to. In 2015, the Asia Pacific region overtook North America by both HNWI wealth and population for the first time ever, according to the World Wealth Report 2016 released on June 23 by consultancy Capgemini. That makes Asia Pacific the biggest market for wealth managers globally.

The region’s HNWI saw their wealth increase 10% last year, the highest in the world, said Capgemini. Wealth in Asia Pacific is projected to be $42.1tr in 2025, versus $106tr for global HNWI assets (see chart opposite).

Wealth creation In Asia, it is no secret that entrepreneurs hold the keys to the kingdom for the wealth management industry. Unlike in Europe, the focus of Asia’s rich is on wealth creation, not simply wealth preservation. So catering to this segment with a full suite of private as well as investment banking services is crucial for any bank.

“We know that entrepreneurship is the most significant source of HNW wealth across key markets in Asia – in fact, as much as 46% in China,” said Stephen Richards Evans, global head of UHNW proposition, private banking, at Standard Chartered.

And as these entrepreneurs grow their business and personal wealth, they become more aware of the need to work with professional advisers to carry the family’s prosperity into future generations.

“In particular, active entrepreneurs need access to investment banking style services and look to the sophisticated use of leverage to realise both their personal and corporate growth ambitions and retain business control within the family,” said Richards Evans.

Yet the one bank approach is a relatively recent phenomenon, according to Pathik Gupta, head of wealth management, Asia Pacific at McLagan, a consultancy. Only a decade ago private and investment banking were largely separate businesses.

The global financial crisis, coupled with growth in entrepreneur wealth, have changed these dynamics. Similarly, bankers have moved on from being fixated on pushing individual products and hoarding bonuses to, as one banker put it, “playing nice in the sandpit.”

“Banks today are very open about encouraging collaboration and are offering different products and solutions to increase the overall share of wallet they can capture from a client,” Gupta said.

Still, this collaboration would be for naught without the appropriate monetary rewards. Bankers on both sides require what Gupta calls a “clear line of sight” on their financial incentives from the get-go.

“In the past, many banks lacked the proper incentives like fees and mutual recognition in the profit and loss for work done that involved both the private and investment bank,” said Jonathan Hollands, managing director of executive search firm Carraway Group.

Banks need to incentivise collaborative behaviour via revenue sharing and by matching pay and bonuses with the ability to cross-sell between the private and investment banks. But those efforts must not stop at financial rewards. To fundamentally change behaviour, senior management has to lead the way, said Hollands.

The lack of a proper rewards system has given private bankers good reasons to be territorial, especially if clients start interacting with multiple touch points inside the bank. Relationship managers are hired for their ability to attract client assets, but this is harder to do if those clients becomes institutionalised within the bank.

Banks have certainly not been blind to this. Francis Liu, UBS’s regional market manager for UHNW Greater China, believes that the winning formula is to “share the harvest”. In addition to staff rewards, banks have also tweaked their management information systems to better recognise profits derived from collaboration.

Superior client experience

The benefits of building an integrated bank are easy to see. Standard Chartered’s Richards Evans believes universal banks that have both private and investment banking capabilities offer a distinctly superior client experience in terms of a “straight through train”.

This means identifying client needs and crafting solutions and execution, all without the need for multiple handshakes in the process or outsourcing elements of the analysis or execution.

Serving clients on a private and corporate basis also gives universal banks a level of intimacy that is not enjoyed by the pure play private banks, even when they work with a third-party investment bank.

“I like to think of it as a relationship where the private bank is the general practitioner who diagnoses the patient and recommends the specialist, and our investment banking counterparts – or in our case, the product teams with the investment banking capabilities that sit within our corporate and institutional banking segment – as the surgeons doing the actual operation,” Richards Evans said.

The private banks with the strongest support from their investment banks, including Credit Suisse and UBS, have wealth management at the heart of their strategy. That support has helped bolster both banks’ dominant positions in Asia. They clinched the third and first spots, respectively, in Asian Private Banker’s 2015 league table, with assets under management of $151bn and $274bn.

UBS started the “gradual evolutionary process” of establishing its one bank strategy more than a decade ago, according to Liu.

The key to its success has been the creation of an intermediary to bridge the gap between the private and investment bank, a unit called financing, risk and corporate solutions (FRCS).

The department, which has been developed over the past six years and was recently renamed from institutional solutions group, is staffed by some 15 former bankers in Asia Pacific. Its mandate is to source, structure and execute transactions for UBS’s wealth management clients, working closely with the investment bank.

Today, FRCS is not only responsible for its own P&L but is also a highly profitable part of UBS’s operations in Asia.

“Streamlining our operations this way reduces the silo mentality between the different parts of the bank as well as helps optimise resources and balance sheet risks for the group,” Liu said.

Crucially, FRCS is staffed by bankers who used to hold senior roles in departments ranging from investment banking and private equity to structured finance and trading. That approach is essential, said Liu, as private bankers are not always familiar with “what is on the other side of the fence” and may miss opportunities.

One notable deal the bank sealed this year in which FRCS played a big role was when it facilitated a cornerstone investment and structured finance solution for a financial institution in Asia to support an upcoming IPO worth more than $8bn. The challenge was not simply one of financing, but going a step further to look for strategic investors that would be the right fit for the IPO, said Liu.

To further integrate its private and investment bank, UBS has put out a guidebook of references that shows how to provide holistic banking coverage from a country, product and solution perspective. Its annual Apac President Awards also recognises cross-divisional efforts that produce the best integrated solutions.

Strategic shift

Still, analysts say the implementation of the one bank model has been patchy. Universal banks, for one, have been criticised for not doing enough to maximise client relationships. Many commercial banks in Asia can call up an impressive list of small and medium enterprise customers, yet few have the private bank assets to match. HSBC is not one of those banks. It ranked fourth in Asian Private Banker’s league table last year, raking in assets under management of $112bn. And a big part of that was down to its commercial bank.

The private bank underwent a strategic shift some years ago when it decided to align much more closely with the corporate and investment banks, according to Bernard Rennell, head of global private banking for Asia Pacific. Underpinning this shift were HSBC’s huge commercial banking business and the recognition that many of its clients are family-owned or controlled.

“We already possessed a natural client base that was just waiting to be tapped,” Rennell said. “Gordon (French, HSBC head of global banking and markets Asia Pacific) and I work very closely on an ongoing basis to discuss client needs, whether it’s an IPO or merger and acquisition, corporate banking or high yield bond, or structuring the financing for private equity, hedge fund, or asset management.”

In HSBC’s case, the ability to provide bread and butter products via the commercial bank paves the way for event opportunities.

“It’s not just about being able to bag the big event mandates, but also servicing the day-to-day needs of the client, whether that be payments and cash management, forex or trade finance,” said French. “The event opportunity is just the icing on the cake.”

There are drawbacks to being integrated, of course. Brand damage is just one of the risks, said Keith Pogson, senior partner for financial services, Asia Pacific at consulting firm EY. For example, some clients may find it hard to place their trust in integrated banks after some were caught up in scandals like the 2008 Libor rigging.

Banks also need to think about compliance at every step of the relationship and watch out for potential conflicts of interest situations. “If a bank sells a particular bond to a client but its trading desk happens to be shorting it, then the client could end up on the wrong side of the trade,” explained Pogson.

Those dangers are not lost on the banks. While there are risks, having a joint coverage model helps to mitigate them. HSBC, for example, has its various sides represented in deal teams to prevent conflicts.

UBS too applies an integrated compliance model to ensure consistent compliance standards across the investment bank and wealth management. “Transparency and disclosure requirements under today's regulatory framework have helped financial institutions minimise such issues,” UBS’s Liu said.

Truly integrated

As for Credit Suisse, its journey towards integration was cemented by the bank’s reorganisation last October, when Asia Pacific became a standalone unit and the P&L of the private and investment bank were unified.

The bank has been one of the most vocal about its ambitions for Asia, announcing this year that it intends to boost its relationship managers in the region to 800 by 2018 from 600 at the end of 2015.

A key positioning of Credit Suisse’s private bank is to also be the investment banker to the private individual and entrepreneur, said Francois Monnet, head of Greater China private banking, Asia Pacific.

To enable this, Credit Suisse has moved a number of top investment banking executives into critical management positions. In November, it promoted then Asia Pacific head of investment banking department Vikram Malhotra to executive vice-chairman and to head a new unit focusing on UHNW entrepreneurs.

Then in February, Carsten Stoehr, a long-time Credit Suisse banker, rejoined the firm in the newly created role of head of financing group Asia Pacific. The unit was created to bring Credit Suisse’s various capabilities, including emerging markets financing, equity share backed lending and structured lending, under one roof.

The Apac financing group is the focal point for structuring, risk management and syndication of UHNW entrepreneur clients’ co-investments that fall outside of existing market trading. By being integrated, the team says it can address the entire spectrum of financing activities, from recourse to non-recourse, equity and pre-IPO, share backed financing, structured corporate risk and corporate loans. “As volumes across various products have dropped, we need to be able to look at our one unit of resource, whether that’s capital or balance sheet, and how to deliver returns that are relevant to the client strategy based on those resources,” said Stoehr.

The ability to co-ordinate financing is a crucial piece of the puzzle. It is not enough to have the lending and structuring capacity – banks also need to syndicate those credit risks out of the P&L.

The financing group has three key components. First, trading and risk management have oversight of the balance sheet and capital utilisation. Second, the structuring arm works with investment banking coverage and private bankers to find the best way to structure deals, and with trading and risk management to mitigate risk.

Finally, the task falls to syndication to de-risk, hedge and sell down to bring velocity into the balance sheet. This can take the form of single or pooled assets, using liquidity from other banks, private bank clients or institutional investors, via structured credit solutions or a portfolio approach in the primary and secondary markets.

While still a relatively new unit, the financing group has a big part to play as Credit Suisse homes in on its richest clients in Asia. About 60% of client assets in its private bank are ultra-high net worth and the remaining 40% high net worth. The bank’s two-pronged strategy is to asset manage high net worth clients but asset manage and “IB manage” the ultra-high net worth segment, according to Monnet.

All that would not be possible without the high degree of integration at Credit Suisse, and if Asia was not run as its own vertical.

“If you talk about integration, very few banks have a division in Asia like Credit Suisse with this level of accountability and autonomy,” said Monnet. “We are closer to our clients and better understand their needs, while having a faster decision-making process.”

The fact that the bank set the ball rolling a decade ago by introducing and tracking collaboration revenues is also significant.

“This was important because it came from the top,” Monnet said. “The next thing you need is an organisation that is obsessed with making this collaboration happen. Once you have the strategic intent from the top, with a dedicated team in place to activate the process of collaboration, as well as the appropriate incentives system, then you have a truly integrated bank.”

Those efforts have borne fruit. This year the private bank originated the HK$742m ($96m) Hong Kong IPO of Union Medical Healthcare, a relationship it nurtured for several years until the client was ripe for a listing. On the debt side, Credit Suisse was a bookrunner on Changchun Urban Development & Investment Holdings’ $400m bond.

Work in progress

It is clear, though, that the one bank is not for everyone. Small or mid-sized private banks trying to emulate the model will probably find it tough going to generate enough flow for the investment bank.

“An integrated solution requires not only willingness and ability, but also resources,” reckoned UBS’s Liu. “For example, the wealth management unit has to have sufficient scale in client and deal flow or it would be hard to justify splitting bankers’ time and attention.”

In addition, a set up like this does not come cheap. UBS’s FRCS, for example, is manned by former heads of department. “It isn’t easy to hire the people with the right know how, and the compensation has to be attractive enough,” Liu added.

There is also no magic number for sharing fees. “The reality of profit sharing is always difficult to simplify,” said Pogson. “You have individual and team performance, cross-selling and whole of firm performance. Most schemes depend on the overall performance of the house. People allocate this in different ways.”

And even after years of striving to be integrated, the one bank model is still a work in progress. “Getting everyone on board is a continuous challenge,” said a private banker with a Swiss bank in Asia.

That is why the likes of Credit Suisse have training programmes for their relationship managers to help them build networks with the other parts of the firm such as investment banking and asset management.

Antoinette Hoon, private banking advisory services partner at PwC Hong Kong, sums it up by saying there is no right or wrong approach when it comes to fostering collaboration between private and investment banks. “It all depends on the business model of the bank and the culture it wants to cultivate,” she said.

To be sure, what was once a wall between the private and investment bank is quickly being torn down, and bankers agree that the trend of integration is one that the industry will increasingly adopt.

Not everyone has successfully cracked the model of the one bank, and a few will rise to the top. But if the early adopters are anything to go by, the one bank approach is here to stay.