By the time Martin Winterkorn, the former Volkswagen CEO, arrived at his office on September 21, 2015, his company had lost 20% of its market value. By the end of the next day, VW had lost a further 17%.

The reason for this value shock was the news that the company’s software had misrepresented emissions on roughly 11 million cars worldwide. A governance flaw was revealed with titanic consequences. Governance gaps, or flaws, pervade the global corporate environment, which is why investors have been demanding more transparency and improved governance practices for decades.

Unfortunately, the case of VW is no anomaly. Instead, VW is only the most recent example of a global company to have fallen from grace as a result of internal (also known as endogenous) risks playing out. Some of the most infamous corporate shocks have come from underpriced internal risks which can range from rogue trading and accounting fraud to disgruntled or misguided employees in research and development. For example, over 30% of cyber breaches are committed by employees and internal sources, according to an IBM report from 2014.

These flaws have brought down the biggest, oldest and most reputable companies including AIG, Enron and Lehman Brothers.

No forewarning

Regulators such as the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Bank for International Settlements are aware of the problem and so have set out detailed guidelines on how companies should report their internal and external risks. Some companies, such as airlines and oil companies, have to detail 10-15 risk types in their publicly available risk reports. Yet there is no mechanism to forewarn investors or to financially quantify these risks. When bad news hits, markets are unprepared and investors push the sell button.

More is being done. Countless non-governmental organisations such as Coso (Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission) and auditing firms, including PricewaterhouseCoopers, have published frameworks to improve companies' risk management. Most involve improved oversight processes and a more active role for board committees such as the audit committee. This is having some impact as a March survey by PwC of 1400 bank CEOs shows that 64% intend to restructure their risk management. In addition, two thirds see cyber risk — a major internal risk —as a barrier to growth.

Yet investors, and probably most executives, cannot monitor growing internal risk, much less factor it into their required rate of return of the equity or debt of a company. This is because investors still use old models, such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model, which largely only quantifies the risk of fluctuations in stock prices and benchmarks but omits internal risk factors.

Global complexity

What makes the internal risk issue so acute today?

One contributing factor to skyrocketing internal risk is the long bull market. Since the beginning of co-ordinated QE action by central banks policies, equity markets have risen steadily producing the second longest bull market in history. As a result, companies have been focused on growth and not limiting risks.

Another factor is the complexity of global operations. A 2015 study by the National Association of Corporate Directors of global companies with total assets of over $16tr lists oversight of risk factors as among the prime challenges for directors. With 55% of global growth to come from emerging economies by 2019, the differences in regulations, governance and culture make controlling risks tough across international operations.

Reputation risk is a further threat. Eighty four per cent of S&P500 company values are intangible assets, which include elements such as intellectual property and reputation, according IP specialists Ocean Tomo. Yet these areas are particularly vulnerable to mood swings which are intensified by social media and jittery investors. The case of Arthur Andersen — the accounting firm which failed following the publicity linked to its role as Enron’s auditor — reveals how fast revenues can dry up in the light of reputational collapses.

The problem with internal risk is that it's hidden and not factored into company valuations. Internal risk is often misunderstood and inevitably underestimated and therefore, mispriced. Calculations by Management & Excellence (M&E), estimate that the internal risk is normally between 2x and 5x the current discount rate. This means that investors are massively overpricing their investments in companies and are not getting nearly the returns they should in view of these high risk levels.

Its most perfidious characteristic is that institutional investors rarely understand, let alone attempt to quantify, these value-bombs nor their explosive consequences. It's like an iceberg which is largely underwater and can sink a big ship. The implications for investors are clear. Simply stated it leads to an over valuation of asset prices and underestimation of internal risks. An investor buying company paper with a weighted average cost of capital of 15% might really be entering into a risk of 50%.

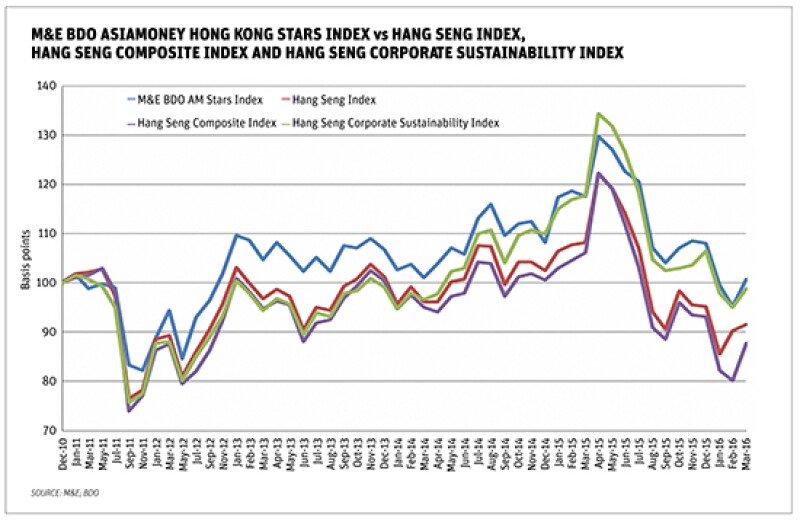

The table above shows M&E's estimates of discount rates reflecting embedded risk in 10 of Hong Kong's leading blue chips. These estimates are based on public information that is available to all investors. Internal audits of these companies would certainly yield more accurate internal risk discount rates. It’s worth noting that the relatively weak transparency of HK and Chinese companies is likely to skew these estimates more than in the case of US, European or even Brazilian listed firms.

M&E's calculations show that companies with top governance scores and records generally incur only a third of the internal risks of poorly governed companies.

William Cox is CEO of Management & Excellence (M&E) and received his PhD from the London School of Economics. Mathew Garver is President of M&E and received his graduate finance degree from Oxford. Vivian Chow is Senior Manager in the Risk Advisory Services at BDO Financial Services, Hong Kong and graduated from the University of California. M&E and BDO co-operate in Asia in offering RoI of intangibles services.