Earlier this year, two men posed as a gay couple and toured the western suburbs of Sydney pretending they were house buyers. The two were actually hedge fund manager, John Hempton, chief investment officer at Bronte Capital, and economist and Variant Perception founder, Jonathan Tepper.

What they found shocked local banks, regulators and markets and has become known locally as the “Big Short” issue, in a reference to the recent film about the global financial crisis. Their conclusions were stark: Australia faces a massive housing bubble propped up by dodgy loans. It was a repeat of the disastrous US housing bubble. And when the bubble bursts, those lending Australians money to buy houses — the major banks ANZ, NAB, Westpac and Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) — will be pummelled.

Tepper predicted a doomsday scenario for Aussie banks with dividends cut entirely, forced capital raisings and stock-price crashes of 80%. The report was the latest front in a savage attack on Australia’s major banks by hedge funds and short sellers which has pushed their share prices to multi-year lows.

The world has certainly changed for Australia’s big four banks. They face slowing domestic economic and credit growth, which is expected to crimp earnings, margins and dividends.

As one senior banker who did not wish to be named told Asiamoney: “We continue to generate business, but it’s tough out there from a loans perspective and margins are falling. People aren’t borrowing like they used to across the board; there’s been a tightening up of investment loans and housing loans.”

And significant risks do remain, particularly in Australia’s overheated housing market and a regulatory crackdown that is boosting capital requirements and diluting returns on equity.

But the doomsday scenarios hedge funds tout is wide of the mark and the banks are responding to their new environment. Three of the four have appointed new style conservative CEOs who are focused on running tighter ships, with a strong domestic focus, and winding back their predecessor’s grand global ambitions.

“No one is running around panicking,” the banker said.

Stranglehold

After the global financial crisis, Australia’s major banks became market darlings as local and international investors bought them as rare high-yielding safe havens.

Offshore banks, burnt in their home markets, retreated from Australia and smaller lenders struggled to get funding. The big four banks, protected by government deposit guarantees, tightened their stranglehold on the local market. The China-driven commodities boom also kept the Australian economy and the housing market buoyant, fuelling banks’ record profits and dividends.

But around March last year, things started to change as investors reassessed the banks’ risks. The depth of the commodities slowdown had become apparent as prices for the likes of iron ore crashed when Chinese growth faltered.

CLSA bank analyst, Brian Johnson, says the four-year rally in Australian bank stocks had been fuelled by “near relentless buying from structurally underweight international institutions chasing dividends as funds have flowed into international income funds”.

But with the weakening Australian dollar, he says the banks are now being caught up in an unwinding of that “Australian dividend yield carry trade”.

Concerned about the banks’ too big to fail status, the Federal Government also hit the banks with a regulatory crackdown at the end of 2015 following a ‘root and branch’ look into the Australian financial system headed by former CBA boss David Murray. In anticipation of higher capital requirements, the major banks last year tapped markets to the tune of A$18bn ($13.6bn), diluting their return-on-equity, which according to KPMG in a report called Courage Required fell from 15.5% to 15% in 2015, with more falls likely.

Adding to the concerns, the banks’ shares crashed as hedge funds, particularly, attacked with most bank stocks falling around 35%.

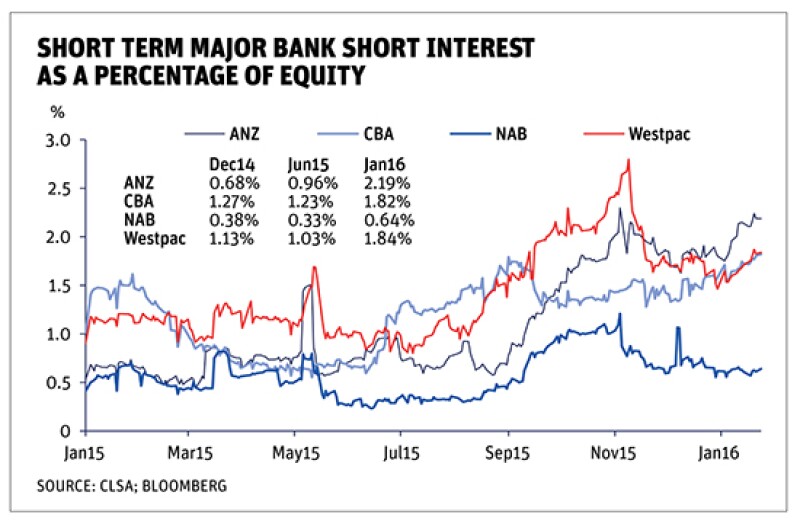

As Johnson notes, net open short positions have increased substantially for Australian banks, particularly for ANZ, CBA and Westpac (see chart below).

The banks have also been hit by a raft of scandals in trading, financial planning and insurance that has severely damaged their reputations. Earlier this year, a sacked ANZ executive claimed there was a toxic culture of sex, drugs and bullying in the dealing room of ANZ’s global markets division. In a statement at the time, ANZ said the executive making the allegations had been dismissed for serious breaches of its Code of Conduct and it would be vigorously defending the court application. Then in early March, financial regulator the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) launched legal action in the Federal Court alleging ANZ rigged interest rates.

Not that the other banks are immune. CBA has been hit by a raft of financial planning scandals, and again in early March, chief executive Ian Narev was forced to apologise after a media investigation found the bank had been using unfair and outdated methods to assess some claims from insurance customers.

New world order

But amid the dramas, the banks have been quietly adapting to the new world, changing their leadership style and scaling back ambitions.

Alphinity Investment Management’s Andrew Martin notes that three of the major banks have relatively new CEOs.

“They’re all very different characters to what came before them,” he said. “But they’re all experienced bankers and they have all been through a lot. In general, they’re reasonably conservative guys. They’ve been able to set themselves for the times and that’s probably a good thing.”

At ANZ the flamboyant Mike Smith, who drove the bank into Asia, made way for his chief financial officer, Shayne Elliott, in January.

Meanwhile, Westpac’s previous CEO, Gail Kelly, was one of the country’s great business icons, becoming the first female chief executive of one of Australia’s big four banks in 2008. In February last year, she was replaced by Brian Hartzer, a seasoned banker who had held senior roles at ANZ and was most recently chief executive of British retail for Royal Bank of Scotland.

CBA’s New Zealand-born Narev is the CEO with the longest tenure, taking over from Ralph Norris in December 2011.

One of the first things the new CEOs have done is to halt or unwind the grand global ambitions of their predecessors, and put a greater focus on domestic operations.

NAB’s Andrew Thorburn, who became CEO in August 2014, taking over from Cameron Clyne, has continued dismantling the company’s UK failed expansion, which saw the destruction of billions of dollars of shareholder funds.

Thorburn, like Elliott, typifies the new breed. When seeking to replace Clyne, Thorburn’s pitch to the NAB board centred on reorienting the bank’s culture to become more customer-centric and exiting the UK to focus on home markets. He has acted and announced a structure to leave the UK via a demerger of Clydesdale Bank.

ANZ’s Elliott has also flagged a new domestic focus, and is scaling back the bank’s Asian presence and abandoning Smith’s goal of driving 25% to 30% of ANZ’s earnings from Asia (see box).

The new CEOs are also putting their stamp on the banks through management restructures, particularly at ANZ and Westpac, with a view to greater operational efficiencies and to position certain units for sale.

The banks have already started offloading assets. NAB announced the sale of its life insurance business to Nippon Life, and ANZ sold its Esanda dealer finance business to Macquarie Group. Analysts expect more sales in the future.

The restructures are also designed to facilitate staff reductions and cost cuts. After creating a new consumer banking division last year as part of a major restructure, Westpac’s Hartzer is now overhauling Westpac’s investment banking division, Westpac Institutional Bank (WIB), which is suffering from tighter regulation and margins.

The WIB restructure is expected to see 80 jobs cut out of a total headcount of 1800. That is symptomatic of what’s been taking place across the industry. In the second half of last year the major banks are estimated to have jettisoned around 3,000 staff, but are avoiding the politically explosive, head-line grabbing mass layoffs that have tarnished their reputations in previous credit-cycle downturns.

Investor angst

But investors are fretting that the new breed of CEOs will also become tight with dividend payments with some fearing that payments will be cut.

“There is likely more pressure on dividends,” agrees Alphinity’s Martin. “While I don’t think there is going to be wholesale cuts to dividends across the banks at all unless we enter a worse than-expected credit cycle — which I just don’t see near term — we are likely to see much lower dividend growth in the foreseeable future.”

“Some banks (the business banks) are already at the top, or even above, payout ratio targets,” Martin added. “This is OK if all goes according to plan and they can grow into it, but does leave them more vulnerable to any [economic] hiccup.”

The problem with hunkering down is the banks become even more exposed to domestic economies and regulation.

According to a recent PwC survey, regulation is the greatest concern for Australian banks, ahead of macroeconomic factors. Bank regulator the Australia Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is finalising its stronger capital requirements this year in the wake of the Murray-led Financial Services Inquiry, which is expected to trigger another round of ROE-dilutive capital raisings.

And CLSA’s Johnson says there are still concerns that Australian banks are under capitalised relative to global peers even after the 2015 capital raisings.

“We estimate the four major banks are still around A$32bn short of capital,” he says. Another analyst who did not wish to be named believes the Australian banks need to raise A$40bn in total, but have raised just A$18bn.

Asiamoney asked all four major banks if they had plans to raise further capital, or to cut their dividend payments, and all declined to comment.

But it’s easy to forget the Australian banks’ enormous pricing power, particularly in the home mortgage market, and the banks have shown a willingness to use this power to protect against higher capital requirements and lower growth.

The four major banks control 80% of Australia’s owner-occupied lending market and have exposure to almost $1.2tr of mortgages, according to bank regulator APRA. The housing market is particularly important to CBA and Westpac, which have 27.2% and 23.8% of the owner-occupied lending market respectively.

CLSA’s Johnson notes that banks have been using upwards repricing of home loans to offset the dilutionary impact of capital raisings.

That pricing power has worked in a buoyant housing market, but that could change if Australia’s housing market bursts, as Hempton and Tepper predicted in the Big Short report.

In the wake of the report, the banks and regulators have vigorously defended their major banks’ lending practices. A NAB spokesperson told Asiamoney: “Home loan applications made through NAB’s branches, digital channels or mortgage broker network are considered on a case by case basis taking account of individual circumstances. We continually review our risk settings, considering a range of economic factors to manage the risk for our customers and our business.”

One senior banker at the big four said: “If there was any problem in the housing market, it would well and truly have been exposed by now”. He notes the debate that the housing market is overvalued has been going on since 2003.

Ultimately, the housing market, and the major banks, will only become vulnerable if Australia tips into recession. For now, the economy is showing surprising resilience despite the strong downturn in the resources sector, which makes a GFC-style implosion remote. Growth in the December quarter was a better-than-expected 0.6%, taking annual growth to 3%. That puts growth ahead of any other G7 country and gave banks a relief rally at the start of March.

AMP Capital’s chief economist Shane Oliver says a recession is unlikely, because while mining investment has fallen, that is being offset by stronger non-mining activity including tourism and education. “Of course if the global economy went into recession it may be a different story but that seems unlikely to, albeit the risks have increased this year,” he said.

And while households remain highly geared, which increases the risks to banks should unemployment rise, corporate Australia has successfully deleveraged and their “ability to service debt is phenomenal on average”, Martin says. “It’s hard to see how you have a serious credit cycle in that environment.”

But what is clear is that both earnings and credit growth will certainly slow. The test now for Australian banks is whether they can adapt to the new environment and how much time investors will give the new CEOs before they expect to see a meaningful improvement in share price and earnings. The challenge is only just starting.

| ANZ: Rethinking Asia Since being elevated from chief financial officer to the top job in January, new ANZ chief executive Shayne Elliott has restructured ANZ’s management and been forced to deal with a series of scandals. But investors are focused on the future of the bank’s ambitious ‘super-regional’ Asian-expansion strategy. The strategy was the brainchild of Elliott’s predecessor, Mike Smith, who sought to differentiate the bank from its less adventurous local peers.

“While we have built a strong Asian franchise in a short period of time, driving value from Asia in the foreseeable future is not about expanding and doing more. It will be about refining what we already have,” Elliott told Asiamoney. “This means that in some areas we’ll continue to grow but in others we’ll be smaller and more focused than we are today. “I cannot conceive of an ANZ where Asia is not an important part of why we offer customers, any more than I can conceive of a time where ANZ is not in New Zealand or Western Australia or Queensland,” Elliott added. ANZ watchers say Elliott couldn’t be more different from the high-profile Smith. “He’s very open,” said one person who has had significant interactions with Elliott in his role as chief financial officer. “There’s less bullshit about him.” Under Smith, ANZ’s Asian strategy was simple: grow at all costs. But CLSA’s bank analyst, Brian Johnson, says ANZ suffered from what he calls a fundamental rule of the universe: “When a new player comes into the market, their quality of new loans and business is lower than the incumbents.” Johnson says the incumbent banks don’t fight very hard to keep their bad loans and business, and ANZ was left to pick up the scraps of business left. ANZ’s timing was also bad. Johnson says massive QE stimulus saw liquidity end up in the few pockets of demand for credit growth, particularly Asia trade finance. That, inevitably, saw margins fall; and that dynamic happened to coincide with a structural fall in Asia trade finance. Alphinity Investment Management’s Andrew Martin says Australian investors have lost patience. “ANZ took a long-term view and were prepared to make lower returns than what their shareholders wanted,” he said. “But they’re competing for investment dollars with the likes of CBA and Westpac which are producing pretty good ROEs [return-on-equity] on domestic mortgages. The market could see benefits of the Asian strategy, but [ANZ] tried to do too much too soon and threw a lot of money at it.” Given the difficult market ANZ faces in Asia, Elliott’s options are limited. “It’s not like a sinking ship,” said Martin. “It’s about operating the business more prudently. The focus now is on generating better returns.” Elliott is acting. He has abandoned Smith’s goal of generating 25%-30% of earnings from Asia. “We are not focused on a number,” Elliott said. “35% or 15% – I don't really care, so long as the business is driving value for our customers and shareholders.” He’s also shaken up management, with the exit of Andrew Geczy and appointment of Farhan Faruqui as group executive of international, with responsibility for ANZ’s institutional business in Asia, Europe and America. Elliott is also scaling back operations in Asia to focus on ANZ's institutional business. The bank has closed its emerging corporate business that leant to small and medium-sized enterprises in Singapore, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Indonesia and Taiwan. Some 100 jobs were lost. And asset sales are likely with reports ANZ is trying to sell its 39% stake in Bank Pan Indonesia. “We will continue to look at the allocation of resources and capital to ensure we are getting the best return from our Asian operations,” Elliott said, declining to comment on specific sales. “While it’s no secret we are looking at some of our partnerships, these are still generating a return for shareholders so there is no need to be rushed.” CLSA’s Johnson says write downs are likely and he notes the book value of ANZ’s equity accounted Asian partnership minority investments is a staggering A$5.54bn, which he estimates is at least A$1.3bn above present market values. Elliott would not comment directly on the potential for write downs but said, “the carrying value of our partnerships has always been kept under close review”. Martin says Elliott is the right person to stabilise ANZ’s Asian presence, which will be helped by his institutional banking background. “It will be a hard slog for him,” he said. “But his rhetoric is the right rhetoric.” Still, it’s not easy to flick the switch and find a solution. “Margins are thin. That makes life tough no matter what you do. They will focus a lot on cost and the type of business they’re writing. But at the end of the day you’re in the market you are in,” said Martin. But Elliott said he remains committed. “Asia is a real differentiator for ANZ and will continue to be an important part of our future success.” |