What is the SDR?

The IMF defines the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) as "an interest-bearing international reserve asset". The SDR is not an IMF currency and it is not a claim that can be made on the IMF, but is instead an accounting unit created in 1969. It can be allocated to IMF member countries to give them additional liquidity at a low cost.

The original purpose of the SDR was to support liquidity within the fixed exchange rate financial system established by the Bretton Woods Conference at the end of World War II. When the US abandoned that system — where the dollar was backed by gold — the SDR largely fell out of use, until 2009. During the global financial crisis, emergency allocations of SDR182bn helped supply liquidity to member countries that required it, putting the SDR back into the spotlight.

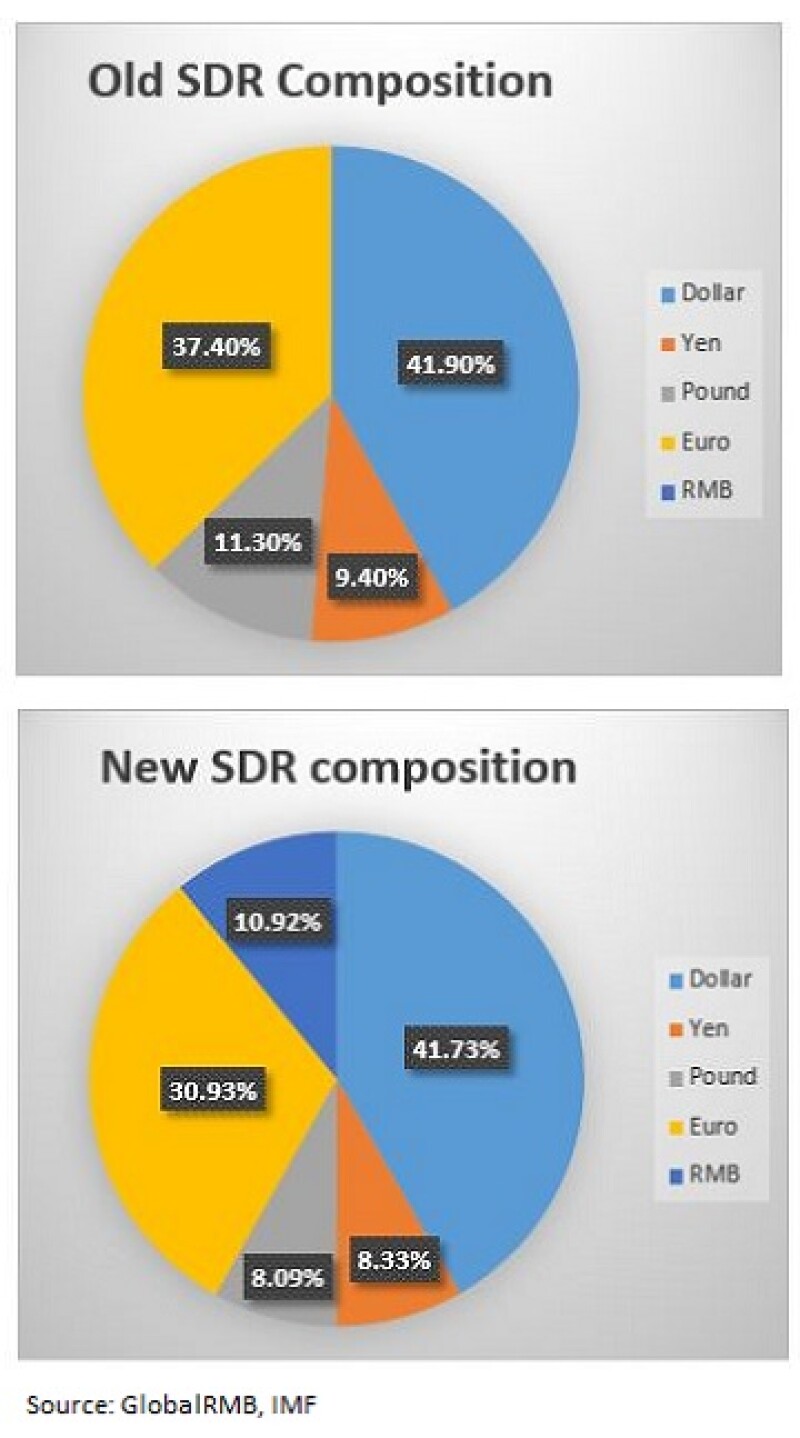

The old basket was made up of the dollar, the yen, the euro and the pound.

What has been decided?

The IMF board of directors, comprising of all member states, met on November 30, 2015 and decided to include the RMB with a weighting of 10.92% as the fifth currency in the basket. This is not really a surprise. In August, 2015 IMF staff issued a report on its review of the SDR basket that said the RMB was likely to be included with a weighting of around 10% to 14%. The RMB’s weighting is based on a mix of its relevance as both a trade and investment currency.

However the change did not happen overnight. Instead the IMF decided to give its members roughly 10 months to adjust their portfolios with the RMB’s inclusion only taking effect at the start of October 2016.

Why should you care?

Because the inclusion is a recognition of how important China has become in the global financial system, even if it does not automatically translate into the RMB becoming a serious rival to the US dollar.

China accounts for around 12% of both global GDP and trade, yet the renminbi is only used for about 2% of global payments. It is massively underrepresented at the moment and China will be hoping the inclusion will help improve the currency’s role as a reserve currency as well as in trade and investments.

What triggered the change?

The IMF reviews the SDR basket every five years regardless of whether a new currency is looking to gain entry or not. For example, the weightings of the dollar and the yen were reduced in the 2010 review. The last time a new currency was added was in January 1999 when the euro became a constituent. However that was a simpler process as the euro just replaced the currency amounts of Deutsch mark and the French franc. It was not considered a review of the basket, just a swap of two currencies for one which is why it took place outside of the five yearly review timetable.

What will be the immediate impact?

The word ‘symbolic’ to describe the RMB’s addition to the SDR has been thrown around a lot.

The inclusion is unlikely to trigger a surge of demand for RMB assets given that central banks have already had 10 months to slowly adjust their positions. And as has been widely pointed out, not all central banks track the SDR basket or use it as a yardstick for their own FX reserves composition.

For example, the dollar is 41.9% of the SDR basket, but represents more than 60% of the allocated reserves as reported to the IMF by its members. On the other hand, the pound, which is 11.3% of the basket, only accounts for 1.9% of reserves.

The RMB has been estimated to account for only about 1% of foreign reserves globally, but it is difficult to estimate how much further than that it will progress in the short term.

That being said, most estimates range from $25bn to $30bn of RMB asset-buying from central banks to adjust for the RMB’s inclusion. Most of these purchases should have already happened over the past 10 months given that China liberalised access to its bond and FX markets for official institutions starting in July 2015.

What will be the longer term impact?

There is little doubt that RMB’s inclusion into the SDR basket will be strategically important to China in the long run. This doesn’t mean SDR inclusion will definitely bring in a large volume of trade or financial transactions denominated in RMB, but there is the potential for it to have a strong influence on China’s onshore financial reforms and the future offshore engagements.

In the medium term, a more diversified set of offshore participants in China’s onshore market, both as investors and issuers, can be expected. In response, onshore firms will launch more sophisticated RMB products for them. In addition, the Chinese central bank will probably further liberalise both the FX and interest rate markets to better fit a more international currency.

Over the longer term, Chinese domestic financial institutions will start catching up with their international peers in terms of business standards and market practice to better deal with the increased competition.

Another interesting development that could happen would be the rise of SDR as an alternative to the US dollar in the global stage.

As mentioned before, the SDR was effectively covered in dust for decades before being brought back to the spotlight in 2009.

There now seems to be a stronger push to create an SDR market outside of the central bank community with the World Bank, for example, printing the first SDR bond in more than three decades in August. The word on the street is that other issuers are looking to follow suit such as China Development Bank and Standard Chartered.

What does this means for RMB internationalisation?

More than you might think. The market might view the RMB inclusion in the SDR as a symbolic move rather than a real economic game-changer, but what is clear is that the inclusion is a milestone for China on its journey to RMB internationalisation.

For the first time, it confirms the international community’s official recognition of the emergence of the RMB as a reserve currency, the global importance of China’s economy and acknowledges the country’s effort in liberalising its capital markets.

This means China will need to improve its standard so that its financial markets can reach the maturity of other developed countries, including those represented in the SDR. And this external recognition, in turn, will give the Chinese regulators the confidence and incentive to further carry out reforms. All of which should help push RMB internationalisation to its next stage.

Does this mean the renminbi is now truly a global reserve currency?

Well that depends what you mean by reserve currency. As part of the SDR basket, this should mean that global reserve managers at central banks will either start adjusting their holdings or start looking at the RMB more seriously.

Either way, the renminbi is a long way off from replacing the US dollar as the reserve currency of choice and enjoying the benefits that go along with that, including the lower cost of funding due to substantial buying of US Treasuries by foreign governments. However, this could change over time provided that China continues on its reform process and the renminbi increases its weight in the SDR basket.