When Norway’s $870bn sovereign wealth fund made headlines in August for excluding four Asian companies because of environmental concerns over their involvement in Indonesian palm oil production, it sparked talk that green or socially responsible investing might finally be getting its time in the limelight.

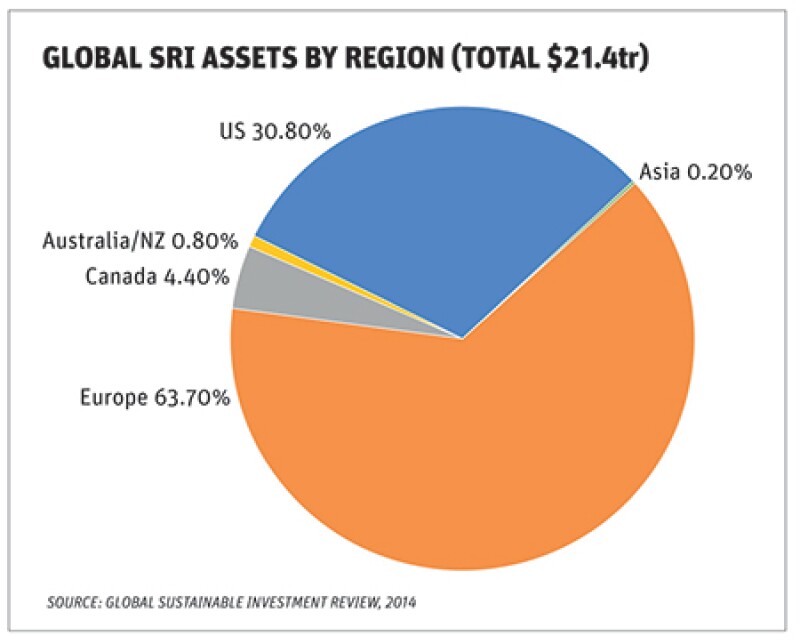

Decisions made by the fund, which also excludes 50 other companies such as Rio Tinto, Walmart and British American Tobacco, are closely watched by other participants in socially responsible or sustainable investing. The asset class has been slowly gaining traction worldwide. Assets invested based on sustainable principles have increased to $21.4tr in 2014, up from $13.3tr in 2012, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, although there is no single definition of what constitutes sustainable investing.

The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance is made up of several sustainable investment organisations around the world, including Eurosif, a leading European group. But while sustainable investing is gaining steam in Europe and North America, it is notably lagging in Asia, where only 0.8% of total invested assets are managed according to sustainable criteria, the Alliance found. That contrasts with nearly 60% in Europe.

Despite the tiny base, interest in sustainable investing is nonetheless growing in Asia. The Association for Sustainable & Responsible Investment in Asia (ASrIA), in its 2014 Asia Sustainable Investment Review, found that sustainable investments in Asia, excluding Japan, totalled $44.9bn in 2013, representing a 22% compound annual growth rate since 2011 (see table below).

Focus on returns

There are plenty of sceptics who say that green investing has too many hurdles to overcome to really become popular in Asia. That feedback is heard in the area of wealth management. Private bankers say investors in the region are singularly focused on achieving strong returns.

“People are just so focused on getting a good return. It’s not that they’re disinterested in the environment but if someone said you can invest in a regular way or in a sustainable way but with a little less return, they won’t sacrifice that return,” says Stuart Leckie of Stirling Finance in Hong Kong, an independent research and consulting firm focused on the pension fund and asset management industries.

Leckie estimates that about 50% of private banking clients in Europe invest, at least in part, in a sustainable way. He puts that level in Asia at perhaps 10%-20%.

Others agree with that broad theory. “Investors in Asia are really pragmatic. They don’t care if it’s green or yellow or orange, they just care about the returns from their funds,” says Federico Burgoni, partner and managing director at consulting firm Boston Consulting Group in Singapore. “The reality is I’ve seen all these products fail miserably,” he adds, likening green or sustainable investing to other specialty products such as Islamic or Shariah funds. Shariah funds, which cannot invest in gambling and alcohol-related businesses, for example, have failed to take off in a big way even in Muslim countries, says Burgoni. He adds that they are most popular in Bangladesh and Malaysia, where institutional investors buy into them to satisfy government requirements.

“The moment you put boundaries up you’re lowering the return, by definition. This is why I’m not so sure [green investing] will make a dent,” he says.

Baby steps

Private banking client interest in sustainable investment varies widely across Asia, however. Bankers say most of the interest is in developed economies such as Japan, Hong Kong or Singapore. Investors in developing economies are far less interested.

This seems fairly predictable; environmental concerns are frequently considered to be a luxury that not everyone can afford. “These are topics that you start to care about when you reach a certain level of wealth,” says Burgoni.

The biggest markets for sustainable investments are Malaysia, Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore, according to surveys conducted by ASrIA. The fastest growing are Indonesia, Singapore and Hong Kong.

In Indonesia and Singapore, interest is driven in part by government policy. In Indonesia, it is in fact a push towards Islamic funds that is backing a trend for socially responsible investing.

Singapore, meanwhile, is positioning itself as a centre for technology and sustainable investing. The city-state has good reason to put the environment top of its agenda. The annual smog that envelops the city every August and September caused by the burning of farmland in Indonesia to clear land for palm oil production has been worse than usual in 2015 because of the El Nino weather effect, which has created drier conditions and bigger conflagrations.

Enid Yip, chief executive of Bank J Safra Sarasin in Hong Kong, a Swiss private bank owned by the Brazilian Safra Group, says that although interest and awareness of socially responsible investing is more prevalent in developed markets, there has nonetheless been some growth in sustainable strategies worldwide, with the scope expanding dramatically.

“SRI investments now extend coverage to include not just resource-related themes but also companies that are actively involved in protecting/preserving the environment," she says. "It also used to be quite rare to see emerging-market names in these investments, but that investible universe is expanding. The concept is more globally embraced than it used to be."

50 shades of green

Socially responsible investing can take numerous forms. One of the most basic methods is simply to screen certain industries or companies, as the Norwegian Oil Fund has done by excluding companies involved in palm oil production. Another form is “ESG integration”, in which investment managers combine environmental, social and governance factors with financial analysis.

Exclusionary screening is the most common method in Europe and North America, but in Asia ESG integration is more popular, according to ASrIA, which also set up the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change. ESG integration accounts for 44% of sustainable investment assets in the region, or $23.4bn, says ASrIA. By comparison, exclusion/negative screening makes up 31%, or $16.6bn. But exclusion and negative screening, which has increased 53% since the start of 2012, is the fastest-growing strategy in Asia, followed by ESG integration, which grew 42%.

ESG screening more often than not focuses more on labour conditions. More than 70% of institutional investors surveyed by Oxfam, an international confederation of 17 organisations focused on alleviating poverty, said they were concerned about labour protection, labour and human rights in purchasing and supply management. That’s not surprising, given headlines about factory fires in Bangladesh or suicides in Chinese tech factories.

The popularity of ESG screening in Asia is leading to demand for better disclosure. Oxfam’s study, which was released this month, found that 64.2% of investors felt that the Hong Kong Stock Exchange should make ESG disclosure mandatory — by making it compulsory for companies to fully disclose information on their ESG performance, for example.

The exchange's standards are much laxer than those in Europe or New York, as it only requires companies to report on six environmental aspects and 12 social aspects — and also does not require listed companies to make disclosures related to human and labour rights in corporate supply chains. The Hong Kong Exchange is currently conducting a consultation exercise to beef this up, however.

India's Ministry of Corporate Affairs, the Philippines Securities Exchange Commission, the Vietnam State Securities Commission and the Singapore Exchange have imposed more stringent reporting requirements on companies relating to sustainable practices over the past couple of years. South Korea passed several new bills requiring listed companies to disclose ESG information.

Green bond growth

In addition to screening companies, another method of sustainable investing is actively putting money into renewable or green energy companies such as solar or wind power. “Sustainability themed investing” is the fastest growing strategy, says ASrIA, growing at CAGR of 56%.

Green bonds fall into this category, and this is one area where Asia has seen notable progress in 2015, not least because of the emergence of India and China as new markets. India saw its debut green bonds, which included a Rp3.15bn ($50m) bond from Yes Bank that was issued privately to the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which then issued the first green masala bond to back its investment.

And in September, CLP Wind Farms issued India's first corporate green bond, a Rs6bn issue that comprised three, four and five year notes.

Meanwhile, Xinjiang Goldwind Science & Technology in July issued China's first green bond, accredited by DNV, a Norwegian-German appraiser. Regulators in China are preparing official green bond issuance regulations and guidelines.

In March of this year, The Asian Development Bank (ADB) sold its first green bond, raising $500m, saying that more than 30% of the notes were sold to Asian buyers. The World Bank, meanwhile, which has issued more than 100 green bonds totalling $8.4bn since 2008, also says it has diversified its Green Growth Bonds programme to target investors in Asia this year.

The World Bank’s green bonds finance projects in member countries that meet specific criteria for low carbon and climate resilient growth through projects such as renewable energy installations, energy efficiency projects, new technologies in waste management and agriculture that reduce greenhouse gas emissions as well as financing for forest and watershed management and infrastructure.

Total issuance of green bonds worldwide reached $30.5bn in 2014, according to the ADB, double the amount in 2013. The ADB also estimated that, since 2010, total bonds issued by renewable energy companies (not necessarily green-labelled bonds) increased to $18.3bn from $5.2bn, most coming from mainland China.

Given the growing number of local issuers, it’s not surprising that some local investors are starting to take notice. Sustainable investment funds are becoming more popular. There are now more than 500 such funds in Asia, up from 404 in 2011, according to ASrIA. Hurdles still exist, though. Despite repeated talk of making more such funds available through Hong Kong’s Mandatory Provident Fund, there is only one sustainable fund there, offered by AIA, out of all the 450 funds on the MPF platform.

Untapped potential

Back to private banking, and the picture is less rosy. Many private bankers say they have seen little or no interest in socially responsible investing from their clients, but research suggests a very different picture — and that there is a lot of untapped potential.

According to the 2015 Asia-Pacific Wealth Report from CapGemini and RBC Wealth Management, Asia’s wealthy investors put more emphasis on having a more positive influence on society than wealthy investors elsewhere. Nearly a quarter, or 24.3%, of respondents throughout the region said they were seeking advice on how to achieve social impact goals, the report found.

Moreover, wealthy investors are leaning heavily on their wealth managers for advice on the topic. Of those investors getting advice on social impact, about half said they were considering their wealth managers to be their primary source of advice. There does appear to be much room for improvement, however, as 66.5% of respondents said they want more social impact support from wealth managers.

CapGemini suggests that private banks are in a good position to tap this demand. High net worth individuals are seeking ways to measure the outcomes of their investing. They are also seeking help in identifying opportunities. There could be opportunities for collaboration — the Singapore-based Impact investment Exchange Asia, for example, offers platforms for social enterprises to raise capital as well as advisory services.

Private banks are stepping up their socially responsible investing and philanthropy departments. Banks such as UBS Wealth Management and Credit Suisse Private Bank have dedicated philanthropy advisory teams.

A big part of what’s driving interest in socially responsible investing is the upcoming wealth transfer. Though many of Asia’s wealthy are still amassing their fortunes, aging entrepreneurs are starting to look to the next generation to pass on their businesses and wealth. Almost two thirds of Asia’s billionaires are now over 60 years old. Hong Kong’s ultra-wealthy are expected to transfer $375bn over the next 30 years, while in Singapore the ultra-wealthy are expected to pass on $110bn, according to a research report in January by Wealth-X and US wealth adviser National Financial Partners Corp.

That generational change could be the driver that Asian socially responsible investment needs, according to figures from CapGemini. Only 55% of high net worth individuals over 40 years old expressed an interest in social impact. For those below 40, the figure was 67%.