Slowing growth in China has put markets in something of a panic. Factory output in August grew by 6.1% from the previous year, but that was below expectations of 6.4%. Investment in fixed assets slowed to a 15-year low of 10.9%. China has cut interest rates five times since November 2014.

Asian investors looking for a home for their wealth have certainly noticed. And their famous tolerance of risk is starting to be challenged.

“There is a sense that clients are aware of slowing economic growth in the region and are becoming more circumspect as a result,” says Arjun Panchapagesan, head of strategic advisory at BSI Singapore, a unit of Swiss private bank BSI, which has just been acquired by Brazilian bank BTG Pactual.

“The boom and bust nature of the Shanghai stock market during the year and the return of volatility in global developed equity markets have created some investor nervousness,” says Panchapagesan. He notes that Chinese authorities' interference in the local stock market in the summer, including suspending trading in 1,200 shares, was very damaging for investor confidence.

“All subsequent steps are being viewed with scepticism.”

Asian investors tend to invest locally. So with the Hang Seng down nearly 25% since June, the Straits Times Index down about 14% and the Shanghai Composite down nearly 40% in the last three and a half months, they are understandably jittery. Since June, Asia ex-Japan funds have lost a net $16.4bn in outflows, according to EPFR Global, a research firm that tracks fund flows. Chinese equity funds have recorded a net outflow of $280m since June.

The last such routs were in early 2014 and during the taper tantrum in 2013, when emerging markets sold off on news that the US was to begin reducing its quantitative easing measures.

China is seeing a particular change in mentality now, argues Raymond Cheung, vice president at Altruist Financial Group, a wealth adviser in Hong Kong that advises many mainland Chinese clients. These “have become more risk averse, especially for the A-share market," he says. "Between the slowing Chinese economy and recent market rout, some entrepreneurs are starting to face a cash flow problem."

The recent volatility is putting pressure on private banks to calm investors. That’s more easily said than done. Private banks have had to work extra hard to regain trust since 2008, when many clients, especially in Hong Kong, found themselves heavily invested in risky structured products such as Lehman mini-bonds or accumulators just as markets tanked. As markets declined, some wealthy investors were left with huge holes in their portfolios.

Since that experience, investors and private banks are treading carefully on leverage.

“I think the key lesson from 2008 for private banks and clients is to use leverage carefully, so that when market conditions turn down, assets are intact to fight another day,” says BSI’s Panchapagesan. “With leverage, the implications of a crisis can be severely magnified."

But while risky products such as accumulators might not have made a comeback, leverage is still alive and well among wealthy Asian investors — a fact that makes the current market rout all the more nail-biting. More than a quarter of Asian high net worth investments are made through credit, compared with a global average of 18.2% according to the World Wealth Report 2015 from CapGemini Wealth.

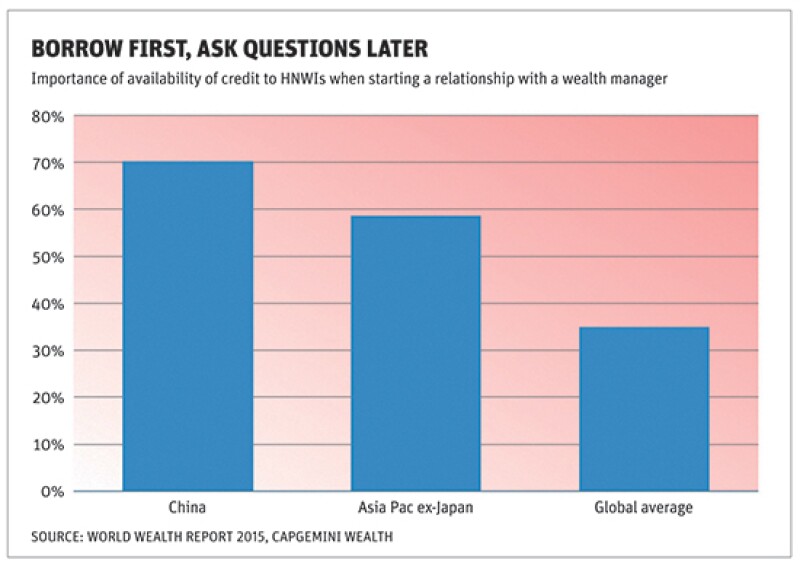

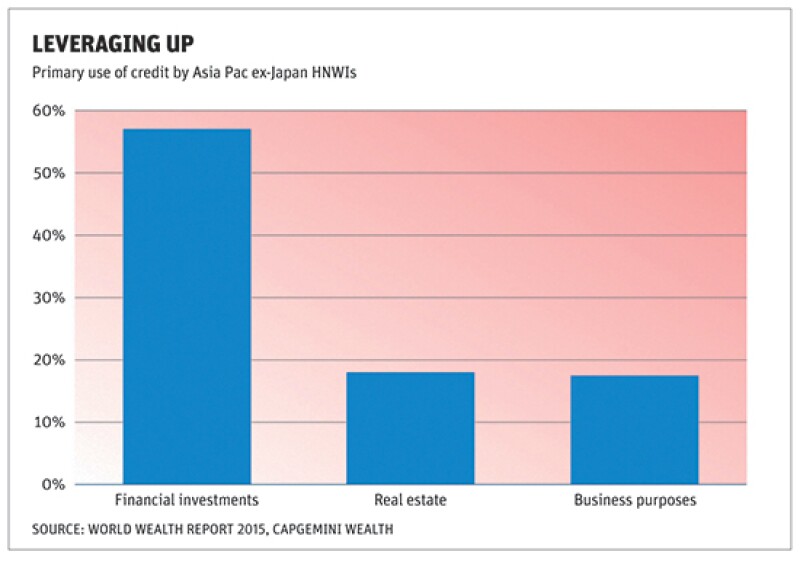

More than anywhere else in the world, Asia ex-Japan high net worth clients put a high emphasis on firms’ ability to offer credit. A majority in the region now cite that ability as important when starting a relationship with a wealth manager, CapGemini found, compared to just 35% of clients worldwide. It is a particular priority for wealthy Chinese, who like to fund securities investment with credit. In Hong Kong and Singapore, they use it to buy real estate.

Much of Asia’s private wealth is new money created by first generation entrepreneurs. Although they may be worth billions on paper, their cash is still tied up in their businesses, which are in growth mode. But many are interested in leveraging their equity to make acquisitions or to diversify their portfolios.

While there are no official figures on how much banks have lent to clients in Asia for investment purposes, lending has unquestionably been on the rise. Banks have been tripping over one another to offer lending to tycoons, and lending has become an important part of private bank revenue streams in Asia. Cerulli Associates, an asset management analytics firm, reckons that financing is the largest single contributor to private bank revenues in Asia Pacific, at 19%.

Lending is also handy for private banks because it keeps their customers more closely tied to them. CapGemini warns that firms without risk appetite or much ability to leverage their balance sheet may find themselves at a disadvantage in the region.

Say one thing, do another

Although many investors are now pulling back from the market to wait on the sidelines, private banking clients in Asia still have more appetite for risk than investors elsewhere. This propensity for risk is often at odds with stated intentions, however. A recent survey from Manulife found that investors in four out of five Asian markets put guaranteed income and capital guarantees as their top two considerations when making new investments. But they also ranked equities as their favourite.

One reason is those same first generation entrepreneurs, still focused on growing their fortunes. According to Manulife, investors in China are willing to take the most risk, holding about 44% of their portfolios in higher risk assets such as equities. This is despite the fact that almost a third of Chinese investors express concern about market volatility.

The study also ranked Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore second, third and fourth in risk appetite, respectively. More than a third of Hong Kong investors said they were worried about making the wrong investment decision, but Hong Kong investors have the strongest preference for direct investment in stocks. Similarly, almost half of investors in Taiwan said they were put off from investing in mutual funds because they were concerned about risks — but at the same time Taiwanese investors favoured penny stocks.

Altruist’s Cheung says another reason for the strong risk appetite in Asia is limited investment choice, particularly in China and other emerging markets. There is also the matter of clients being new to investing. “They do not fully understand related investment risk,” he says, emphasising that education is an important aspect of his job.

Whatever the reasons for it, the mismatch between investor risk appetite and investment intentions is a headache for private banks when markets hit the skids.

Manulife offers up the recent stock market slide in China as a cautionary tale for investors taking on too much risk. Despite speculation that Chinese equities were in a bubble, investors accumulated an additional Rmb1tr ($157bn) in debt to finance short-term investments in stocks before the market peaked in June. More than $3.4tr-equivalent in equity value evaporated during the first three weeks of the market slide alone.

Choppy waters

With various Asian markets down so much in the last three months, private banks are advising clients to hold positions or buy where appropriate. “Clients are looking for well-reasoned analysis of the situation along with some actionable ideas as to how to take advantage of the opportunities that arise,” says Simon Grose-Hodge, head of investment advisory for South Asia at the Singapore unit of LGT Bank, a private bank owned by the Liechtenstein royal family.

Grose-Hodge views current market volatility as an opportunity. While acknowledging that conditions bear no resemblance to markets in 2008, he adds that “if there was a lesson learned it was that central banks are prepared to take whatever action is necessary to stabilise markets, so when central banks step into the markets, it is a good time to follow.”

JP Morgan has noted that after recent corrections, the MSCI Emerging Markets traded at a multiple of 1.28 times price to book value, while the MSCI Asia Pacific ex Japan was at 1.34 times. The Emerging Markets index has only been cheaper 3% of the time since 1989, making further downside unlikely.

Opportunities exist elsewhere too. LGT Bank has been advising clients with excess cash to use the current sell-off to add to their developed market equity holdings, which have been “overly punished” in relation to fundamentals, Grose-Hodge says.

“Our view is that the current volatility is driven more by sentiment more than fundamentals," says Didier Duret, chief investment officer at ABN Amro Private Banking. "We have adjusted to the fact that the Chinese economy is slowing gradually." Although this has created financial instability, Duret sees two elements that will help stabilise financial markets: policymakers providing liquidity and an economic recovery in the US and Europe. Despite recent currency volatility after the devaluation of the yuan, “we do not foresee a full-blown currency war but expect continuing foreign exchange fluctuations,” he adds.

During rocky markets, diversification is key across country sectors, active and passive instruments, according to Duret. Market disruptions can provide opportunities to achieve clients’ medium-term performance goals.

BSI’s Panchapagesan takes a different tack, recommending "protective measures” such as holding higher than normal cash levels and buying equity index put options when volatility is low. The bank sees “more challenging conditions” for equity markets in autumn and wouldn’t be surprised if markets dropped even further in the fourth quarter. For now, it is underweight Asian equities and is recommending a trade finance fund that invests in short-term secured senior loans to Asian companies in the commodity supply chain.

Bargain prices

Investors with exposure to China have had to stomach a lot of ups and downs, but bankers still have favourable long-term views. Duret points out that the Shanghai Composite is still up 50% since the start of 2014. Even with the slowdown of the overall economy, exposure to the Chinese consumer economy is a sensible course for any investor, he adds.

Irene Chow, senior China and Hong Kong equity analyst at Julius Baer, another Swiss private bank, says the sell-off in China is not a cause for too much concern because there are positive drivers down the road, including the reform of state-owned enterprises. Chow cites the suspension in August of trading in the listed entities of China Shipping Group and Cosco as a hopeful sign because “this gives us some confidence that SOE reform is in the cards.”

In September both firms said that their stocks would remain suspended while matters that "may involve a reorganisation of assets" remained under discussion. A merger is widely thought to be on the cards.

Chow and others recommend buying Chinese equities in Hong Kong rather than in China because A-shares are currently trading at about a 30% premium over Hong Kong H-shares. Mainland investors can buy Hong Kong shares through the Hong Kong-Shanghai Stock Connect, although they must first convert renminbi into Hong Kong dollars, which can lead to some losses from currency conversion. The A-share premium is down from 40% back in July, but Chow doesn’t see it narrowing in the near future.

Additionally, Chinese H-shares are trading at PE multiples of about seven to eight times, which looks cheap to many. Chow says investors are best off staying put or perhaps buying more if they are underallocated. For his part, Panchapagesan says that though BSI Singapore is cautious on China, H-shares are looking more attractive as sentiment worsens and valuations decline.

Interest in commodities and gold has seen a very slight uptick. Currency concerns have given gold a boost and in late August gold funds recorded the biggest inflow since February, according to EPFR. Panchapagesan says BSI has some modest exposure to gold and agricultural commodities and can foresee increasing exposure to commodities in the near future.