Piyush Gupta has plenty of ambitions for DBS, the bank he joined as chief executive in 2009. Being global is not one of them.

Sitting down with Asiamoney in the wake of the departures of the chief executives of Barclays, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank and Standard Chartered, Gupta is in pragmatic mood — and perhaps relieved to be away from the pressures of trying to make a global business model work in an increasingly regulated industry.

"I have no desire to be a global bank. There is so much happening in our region. I'd much rather focus on growing the business where we can," he says.

"Our agenda is to be world-class, not global."

Something is certainly going right with that agenda. In August the bank posted another strong set of quarterly results, and while a little down from the record first three months of 2015, the second quarter still extended the bank's run of year-on-year quarterly earnings growth to 24 consecutive quarters.

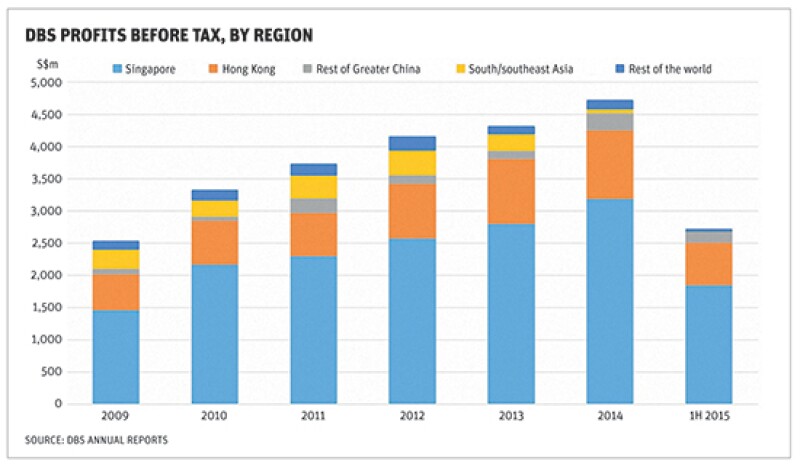

First half revenues were S$5.4bn (US$3.86bn), up 14% from the same period in 2014. Pre-tax profit rose 11% to S$2.7bn. Assets were up 6% to S$440bn.

Revenues in the first half of 2009 (Gupta took over in November of that year) were S$3.5bn, with pre-tax profit of S$1.3bn. Assets totalled S$263bn.

If DBS doesn't want to be global, what does it want to be? For Gupta, the differentiation boils down to two things: a pan-regional focus that he thinks is missing from most of his local competitors, and an ability to service the entire supply chain that he thinks is missing from the globals.

He argues that his regional competitors have mostly chosen to focus on a subsegment of Asia. He sees the likes of CIMB, Maybank and Bangkok Bank striving to be Asean banks. He doesn't see Indian banks in north Asia and nor do Taiwanese or Hong Kong banks have much traction in south or southeast Asia.

"We decided to be the only Asian bank that emulates the HSBC, Citi or StanChart approach of being in all three segments — north Asia, south Asia and southeast Asia. That's because our own view is that over 10 years that’s where the big flows are going to be and frankly already are. If you look at the big movements of capital, it's not within the subsegments, it's across the three."

Then there's product. In the corporate sector, the emphasis is on being a solid transaction bank — and that often starts with trade finance, which Gupta likes to call his "beachhead" when looking to secure new territory. This has been the bank's approach in capturing new clients in China and India in particular.

"We can distinguish ourselves from the global banks because they don't really do that entire supply chain. I'm quite happy to do the warehousing, the receivable financing, the factoring, the discounting, the supplier finance — one of my clients once told me that 'from the farm gate to the factory gate, you guys are part of that value chain'."

Couple that with a commodity risk management overlay, and Gupta reckons he has the most complete trade finance capability in the system today.

| "We can distinguish ourselves from the global banks because they don't really do the entire supply chain." |

Senior bankers at global firms in Asia often profess to care little for what even a firm like DBS thinks about them, but even they will be pleased to note that Gupta feels the bank has traditionally struggled to catch up with them in cash management.

"The globals have all the cash management capabilities that we do, but if we do a lot of good trade finance, the cash management can come as an attendant piece." He cautions, however, that getting the most out of that is going to depend on being able to leapfrog competition in e-commerce and the digital offering more broadly.

It's the first mention of a focus that Gupta will return to, and is clearly playing on his mind at the moment. Although much of his discussion with Asiamoney concerns mainstream banking, challengers are disrupting his thoughts much as they disrupt his business.

New brands and platforms — whether Alipay, the online payment system that was set up to service transactions within Alibaba but has now spread its wings much more widely, or M-Pesa, the mobile telecom money transfer service that has transformed economic life in Kenya — are shaking up traditional banking as equivalent services are in other global industries.

Gupta reckons the correct response for an incumbent is to absorb what the challengers are doing and do it better, by integrating it with the unique skills that a traditional bank can offer — chiefly in risk management.

Back in the traditional world, treasury services are another area that has been a work in progress for DBS for some time, but one that the bank thinks is now at par. It has been a long slog. DBS had a decent markets capability that predated Gupta's time at the firm, but it was very internally focused, choosing mostly to direct its efforts to prop trading and own balance sheet work. One of his priorities has been to make that skillset more available to customers in the region.

"We were already good at rates and currencies, so we added other asset classes like commodities. We think we can compete, and if I'm as good as the big guys I'll get my share of the business."

In debt capital markets, he thinks the bank's judgement to invest a couple of years ago has played out well. But he says there is much more to come, particularly with growing opportunities in renminbi, baht and rupiah, for example.

"It's an area where there is a tremendous opportunity because I think Asian debt capital markets are going to massively grow."

Gupta is also bullish on the wealth management opportunity in the region, and dismisses any suggestion that banks chasing business could be squeezed as they all scramble to service Asia's growing numbers of wealthy entrepreneurs. A hundred banks built a fairly decent business over 500 years in Switzerland, he argues, and while the dynamics have changed, he sees plenty of scope for 10 banks to make a great wealth management business in Asia.

At DBS, consumer banking and wealth management income rose 28% in the first half of 2015 to S$1.8bn, with profits rising 56% to S$650m.

"Do I have to be number one? No. Can I be top 10 and still have a fantastic business? Yes."

Gupta says he has no aspirations to knock a leading franchise like UBS off its perch. "But if I can build a really good number five or seven business which gives me a 20% CAGR and extraordinarily high ROE, what's wrong with that?"

Banking the megatrends

Gupta likes his megatrends. For Asia he boils these down to increasing domestic consumption, increasing infrastructure investment, increasing exports and increasing adoption of new technologies. These are so strong and long term that as long as an Asian banking player can put together a competitive offering and differentiate itself in certain segments, then it can build a good business.

That's the proposition that underlies DBS's entire strategy, but it's one that relies heavily on those megatrends not only playing out as predicted but also supplying plenty of business for the firm in the process. Gupta has previously noted the length of time that people have been talking about Asean market integration, for example, with not much yet to show for it.

"The strategy is based on a view of Asia — that is correct. Our general view on Asia is that if you think 10, 15, 20 years ahead, the shift of economic gravity to the region will continue. This is informed by the demographics, the infrastructure investment needs, the integration of the private sector, the technical development.

"Could any of these drivers change? Yes, but in broad terms we think these are sensible premises to be basing the strategy on."

Within that overall approach, of course, the firm has made specific bets. It made a call on renminbi internationalisation in 2009, building a capability in Hong Kong and better connecting its Singapore business to China.

| "Our view on Asia is that the shift of economic gravity to the region will continue." |

"We got that right, and we made the right bet in 2013 that the Asian bond markets would rapidly need to start building out. I think we've got good momentum on the back of that."

Some bets haven't worked. DBS has long been a cheerleader for small and medium sized enterprises, seeing the servicing of that segment as a proper part of the DNA of a firm that wants to be a regional leader. But efforts to step that up have not gone to plan.

"We made a bet that we would grow out the SME franchise in a much bigger way than we have been able to. It went off because the macro environment didn't support it."

India has also seen the bank run into headwinds, and although Gupta is excited about customer growth in China — DBS had no large corporate customers there in 2010, now it has 600 — he remains cautious about the direction there.

This is where Gupta likes to have his hands on multiple levers. Diversification brings a flexibility that allows him to cope with setbacks, he argues.

"If I have eight engines, and if this one is going slow then I can pull back on that and push the pedal down on another one.

"We've got so many engines going. There are quarters where a couple of them don't work but on balance the fact that we have now had 24 quarters of consistent year-on-year quarterly growth tells you that we have enough of those engines firing to be able to give us real growth."

That still needs work, though. Gupta wants to drive growth in China, Taiwan, Indonesia and India to balance out the geographic mix of the business. Income away from Singapore and Hong Kong doubled to S$1.4bn from 2010 to 2014, but that only represented a shift from 11% of overall group income to 15%.

In the first half of 2015, Singapore accounted for 67% of net profits, slightly up from the first half of 2014, while Hong Kong was at 25%. The contribution from the rest of Greater China and south/southeast Asia fell from 14% to 8%.

Cross-selling

Since the global financial crisis, big bank CEOs have regularly trotted out the mantra that the focus in a capital-constrained world must be on banking the clients they already have more deeply rather than scurrying around to find new ones. Cross-sell is the buzzword, and at some firms it has required a wholesale clear-out of those staff who were too wedded to the old style of product fiefdoms.

DBS has gone through that transition too, although Gupta says that the bank's performance now is built on customer acquisition in certain areas alongside a concerted effort to cross-sell.

"[Before the crisis] we were a loan shop. We had massive balance sheet out and there were large positions in syndications that we had taken out where we didn't even know the client."

What Gupta set about changing will sound familiar to those at other formerly silo-driven firms that now seek to be much more joined up in their approach to clients — not least his old shop, Citi.

"We had this tremendous opportunity because we were so far down the spectrum in terms of cross-sell. The minute we changed the KPIs of our bankers to be more customer focused, we started getting tremendous cross-sell advantage."

That also meant a reorganisation. Trade finance used to be all over the place, scattered throughout the bank's myriad areas. That was put into one single shop, cash management was built up, and treasury services were broadened from their previous prop focus.

| "We are a Goldilocks size — big enough to have some clout, but small enough to be nimble." |

So far, so familiar. Plenty of other firms profess to have become much more integrated. HSBC is notable for regularly breaking out the revenue contribution made through what it calls "collaboration" between businesses. All the collaboration in the world won't help if the individual product skills are missing, and Gupta agrees that a big part of getting the pitch right to clients was filling in the gaps in the offering.

"You have to have competitive capabilities, so that you can say to a client that here are three more things you should be doing with us. Otherwise it’s a case of 'Hey, client, you're not giving me any cross-sell', and the client saying 'But you don't know how to do cash, you're terrible at trade, so what do I give you?'"

Gupta argues that the potential for DBS is particularly promising because of its size, which makes it big enough to matter but small enough to change quickly when needed.

"We have a Goldilocks size — big enough to have some clout, being a top 50 bank globally by balance sheet and market cap, but small enough to be nimble, being focused on six or seven countries that really matter. I can run my management team like a kitchen cabinet — the 20 of us can easily get on the phone together."

One business that has benefited from this approach is private banking, where the connectivity with the retail bank and with investment banking has been stepped up. Gupta put in place what he calls a "wealth continuum", with all the wealth-related businesses brought together with consumer banking. The cost income ratio is below 60%, compared to an average in Asia of closer to 80%.

Wealth management also consults with capital markets every day to consider how distribution into wealth clients can best be used to support transactions.

Customer acquisition still matters for Gupta — not in Singapore or Hong Kong necessarily, where he probably has all the customers he wants — but in markets like China, India and Indonesia.

"We have built out an industrial-scale machinery to acquire customers and there we are talking about thousands of customers. In wealth, for example, that is not only through feet on the street but through electronic channels as well. We are doing a lot of digital customer acquisition."

Regulation is making that process harder. Know-your-customer requirements are ever more onerous and banks around the world are having to deal with legacy issues that are costing them substantial sums. HSBC, for example, has been grappling with issues stemming from the acquisition of a Swiss private banking business in 1999. A conservative jurisdiction like Singapore makes reputational issues even more challenging.

"I turn away about 90% of the European money that comes my way because I can't establish the provenance of it. But I think the power of big data today means that you will be able to establish customer identity electronically with a high degree of confidence.

"What we can know about our customers today is mindboggling. Purely on someone's bank account or history of ATM use, for example, we can know where you work, where you shop, where you eat."

| "I turn away about 90% of the European money that comes my way." |

DBS has long been known for the savviness of its connectivity with consumers based on real-time analysis of transactions, sending local promotions to a customer who has just paid for a product in a shop using a DBS card, for example. David Gledhill joined DBS as head of group technology and operations from JP Morgan in 2008 with a mandate to make such analysis possible and profitable. Gupta cites another instance of where big data analysis is bearing fruit. "We got a lift of eight times in the success of a marketing campaign by targeting a restaurant where we thought it was highly likely customers would go to in the next month."

Making life difficult

Looming over all this development is the shadow of global banking regulation. In answer to whether regulators are making his job harder, Gupta is unequivocal: "Much harder, partly because they are rethinking the whole regulatory artifice again."

After 25 years of going down the route of Basel II and Basel III, regulators are now going back to where it all started, he says.

"Basel IV is effectively Basel I.5. No one wants to recognise that apart from Dan Turullo in the US, who has basically said that Basel is not working so let's go back."

Turullo, a US Federal Reserve governor, has argued for a rethink of how regulation is approached, and has criticised the freedom big banks have to use internal models.

"Everyone else is perfuming the pig. They all want to go back but don't want to say we wasted our time," says Gupta. The result of this denial is a mish-mash of supplementary measures and floors, he argues, that will do little other than negate the Basel construct as it currently stands. Uncertainty reigns.

For DBS, that uncertainty produces a pretty straightforward impact — too much capital. DBS's core equity tier one stood at 13.4% at the end of the first half of 2015, and its total capital adequacy ratio was at 15.3%. "I think we have too much capital, and it hits returns, but I don't have a choice because the uncertainty is so high."

That's the high order impact, but there is another more immediate one for the bank and the industry as a whole — a lack of liquidity in the market. A letter to shareholders from JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon in April 2015 was one of the clearest elucidations of this regulatory consequence, but he is far from alone in identifying it.

| "I think we have too much capital, but I don't have a choice because the uncertainty is so high." |

Gupta argues that while this impact might have been most noticeable in the US, Asia has also been squeezed. He used to be comfortable with the fact that he had large stocks of govvies, US and local, because he could repo it when needed. Today it's different. "I'm going to keep $5bn of cash — I would never have done that before. I would have kept most in liquid assets, but today I'm not sure the liquidity exists for me to repo that out. I'm creating inefficiency, but I'm willing to take that because I don't want to be caught short of cash."

Not much bad happens to banks without clients sharing the pain in some form, and cash sitting idle is no different. "If I'm not making a return on it then I have to price up for a corporate client in order to make my returns," says Gupta.

That said, looking at the total return of a client relationship means that a bank can still price lending competitively if it can be sure of getting sufficient business elsewhere. Gupta returns to the theme of cross-selling, this time in reference to his previous tenure at Citi, where he began his career in 1982 and worked until he joined DBS in 2009.

The post-crisis Citi has been one of the most energetic banks for revamping the way in which it approaches the client relationship, analysing total return and share of wallet in meticulous detail. The result has been an extraordinary resurgence that has taken the firm to the ranks of the very best in Asia. But it was not always so, as Gupta recalls.

"When I was at Citi our whole focus was on ensuring ROE at transaction and product level. If that didn't work then we wouldn't do it. I used to find it very frustrating if a really good client of mine wanted to do an ECM deal or M&A and the global guys would not do it because they would say the returns were too low or the ticket was too small."

That mentality has changed, and few firms could now afford to take such a compartmentalised approach to business. For Gupta, the calculation is a fairly simple one. "It doesn't matter to me if you have done some business with the client at plus 2% or minus 2% if you can demonstrate to me the total return of the relationship is 20%. For me that's ok."

China opportunity

It helps when clients are willing to pay. "Of all the countries we operate in, the toughest market is India. Clients there hate having to pay for anything, and so it is the hardest market for cross-sell."

The Chinese market has been better, though, and is largely built on that beachhead of trade finance. Last year the bank did two dozen capital markets deals for Chinese clients. All those relationships had started with trade finance two or three years earlier.

Gupta might be cautious on China, but he sees a big opportunity for the bank in China's project to internationalise its markets and currency. "Our market share in Hong Kong is about 4%, but in offshore RMB there it is about 8%-10% in total — bonds, trade finance, options, swaps."

He notes that DBS is one of only seven foreign banks to have been granted direct access to the first phase of the incoming China International Payment System (CIPS), which promises to transform international clearing of RMB transactions. Gupta sees the chance to build a settlement and cash management capability into China on the back of it.

When it comes to renminbi internationalisation, the offshore RMB hubs that are proliferating around the world are not the big story, says Gupta. "The offshore and onshore RMB are going to be one currency in 12 months, right? Arbitrage is disappearing, there will be one curve, so it will really be an RMB story."

Banks are already being permitted to repo onshore and take the money offshore, and Gupta thinks that within six months it will be possible to do onshore unsecured borrowing and repatriate the proceeds. This is where the real action is happening.

"This whole thing about 'Am I a hub?', that isn't it. There will be some natural centres, in the same way that the US dollar has natural centres. Tokyo is one, Sydney, Hong Kong, Dubai, Zurich. And this is not because of some US dollar agenda — it is because they happen to be financial centres. And that is what will happen with the RMB."

But a few things still need to happen. For one, there need to be a lot more RMB assets available for international investors to own, says Gupta. That means deepening China's capital markets through allowing more international participation.

He also reckons that more value could be got out of the 30-odd swap lines the People's Bank of China has in place with foreign central banks, and which have almost never been used. China itself funnelled about $3bn to Hong Kong in 2010, and South Korea activated a miniscule portion a few years later. Argentina is rumoured to have drawn several billion dollars from its line.

Gupta would like to see these lines used routinely to expand liquidity. "The way they are structured is that they are only contingency facilities. I recommended to the Chinese and Singapore sides that they redo the agreement and make it a facility that could be used to pump liquidity on an ongoing basis, and that way you get RMB out into the system. You don't need to wait for a squeeze."

Dealing with disruption

Identifying DBS's biggest challenge takes Gupta back to a favourite theme — digital. "The Street is getting completely dislocated by challengers, but you have to do what they are trying to do and add the strengths you have that they don't."

That comes down to two things above all others: risk management and clearing/settlement. Companies like Alibaba are taking a lot of money and placing it out all the way up the yield curve up to five years, for example.

"That's ok when markets are liquid but what happens in a down-cycle? These companies have algo-based systems that sound very sensible but which have never been put through stress."

Clearing and settlement is another unique strength of the banks. Apple Pay, Alibaba and their ilk all come back to the banks for clearing and settlement, notes Gupta. "None of them have replicated all the pipes — the banks own that."

What banks don't have, though, is the flexibility of the challengers. Gupta doesn't see this as impossible to achieve, though, and likes the look of what China's Ping An is doing with Orange Bank, the youth-targeted internet-based direct bank that it set up in August 2014. By March 2015 it had half a million users.

"I think they're doing the right thing. You will see a lot more banks taking the strengths they have and building the digital piece.

"Banks that can get on with that will win."

Gupta sees the Goldilocks size of DBS as an advantage in this. But the danger remains that growing in size or scope makes a firm less nimble. Gupta says he worries about that all the time, although he also consoles himself with the knowledge that he can grow in existing areas without losing the ability to be flexible.

"It's about the breadth of presence that you have — I could double my size in Singapore but still be quite nimble. Doubling your balance sheet doesn't stretch you mechanically. It goes back to whether we want to be global. If I wanted to spread out and put one business into Europe and Africa, it would start to get much harder."

Shareholder pressure for returns and growth doesn't go away, but Gupta is confident that the bank can deliver without being forced to spread itself thinly. "Think about where the growth is: when China slows down it grows at 6%, so the notion that I should expand into a 1% growth region is counterintuitive. Our return targets are 12%-13% and we are getting around 11.5%-12% at the moment."

Firms based in or venturing into more exotic markets than DBS has identified will better satisfy investors looking for a different risk/reward ratio. But Gupta is more than happy to cap the ambition.

"Our shareholder proposition is for you to participate in Asia's growth in a sensible way, with double digit growth rates. We won't give you 20%-30% growth, but we will give you a sustainable return."