On Thursday July 23, at the Melbourne annual general meeting of Victorian electricity company AusNet Services, shareholders blocked an equity raising.

That equity raising was to have funded a possible bid for electricity assets being sold as part of the New South Wales Government’s A$20bn ($14.8bn) privatisation of three electricity businesses.

The shareholders also voted independent director Tony Iannello off the AusNet board. Iannello had been publicly championing AusNet’s planned bid for NSW’s transmission business, TransGrid, the first of the three assets to be sold.

The twist is that the combined vote of two companies – Singapore Power and China’s State Grid Corporation – triggered the sacking of Iannello and the blocking of the equity raising. Singapore Power owns 21% of AusNet and State Grid holds 20%.

The shareholder machinations came at a sensitive time: up to seven consortia had just lodged expressions of interest for TransGrid. Among those were State Grid Corporation, which is reportedly partnering with Australian investment bank Macquarie Group. Singapore Power was also believed to have looked at bidding alone or becoming part of a consortium.

There is no suggestion that Singapore Power or State Grid combined their votes to get rid of Iannello and block the raising, or that it was linked to the TransGrid privatisation. But AusNet will now struggle to bid; a competitor for TransGrid has been removed and the chances of a successful bid by State Grid, which analysts believe is favourite to win TransGrid, have increased further.

The corporate powerplays by Asian operations highlight the global importance and attractiveness of Australia’s power assets. The TransGrid sale is attracting global players seeking strong assets in stable economic environment.

“They all see Australia as an attractive place to invest with lower sovereign risk than other places,” says Mark Coughlin, Australian utilities leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers, a consultancy. “They are good assets and there is a lot of interest in Australia from a risk-return point of view.”

A successful NSW electricity privatisation could also pave the way for energy privatisations in the state of Western Australia. And it could reignite the sale of Queensland’s electricity assets that was rejected by voters earlier this year. Both Queensland and Western Australia’s governments are grappling with surging debt loads and a serious shortfall in infrastructure spending.

Back in the 1990s, the controversial Premier of the state of Victoria, Jeff Kennett, sold off the state’s electricity assets. The privatisation was lauded as one of Australia’s most successful. It let to a more efficient electricity sector and helped boost the economy. The state of South Australia sold off its electricity assets in 1998.

Then there was a pause. NSW, Queensland and Western Australia held onto their power assets. But in recent years, state government debts have surged. Queensland’s is forecast to surge to A$100bn by 2018/2019. At the same time, states face greater infrastructure spending requirements for things like roads.

So the spotlight has again turned to the prospect of selling multi-billion-dollar power assets.

Tale of two states

In 2013, Queensland’s then Premier, conservative Campbell Newman, appointed advisers to look at selling its electricity transmission and distribution sector, which is entirely government-owned. It was a prospective fee bonanza for investment banks, with the sale expected to reap A$40bn-A$48bn.

Meanwhile, NSW moved to offload TransGrid, Ausgrid and Endeavour Energy as part of a A$20bn "poles and wires" privatisation.

But privatisation in Australia has been a political flashpoint, and in state elections in 2015 both Newman and NSW's Mike Baird sought an electoral mandate to sell the assets. They were to have vastly different outcomes.

Newman in particular took a powerful position to the election. In 2012 the former Lord Mayor of Queensland’s capital, Brisbane, had demolished his rival Labor Party, reducing it to a rump of seven seats against the 78 of his Liberal National Party (LNP).

But when he took power Newman’s popularity slumped. Many expected him to lose his own seat in the 2015 election. But most, particularly the bankers working on the energy privatisation and the bidders circling, expected the LNP to retain government with a reduced majority.

What happened on January 31 was a shock. Newman not only lost his own seat, but a massive swing to Labor resulted in a hung Parliament. Labor’s leader, Annastacia Palaszczuk, who opposed privatisation, formed a government with the help of an independent MP. The privatisation was dead.

Over in New South Wales, the story was a different one. Baird won his election and received a mandate to privatise. Newman had been deemed too aggressive and dictatorial, but 47-year-old Baird, the son of NSW’s former Olympics Minister, is seen as the nice guy of Australian politics. Until entering politics in 2007, he had worked in banking for 18 years, latterly as head of institutional banking for HSBC in Australia and New Zealand.

Baird had taken over as Premier in April 2014 when Barry O’Farrell became embroiled in an expenses scandal. He started his push for privatisation of NSW’s power assets, and he wanted approval from voters.

But just before this year’s March election his privatisation plan hit trouble. Global investment banks Deutsche Bank and UBS had been hired to advise the government.

On March 17, just a fortnight before the election, two UBS analysts issued a report on the privatisation. It was titled "Bad for the budget, good for the state". The report said that lost revenue from the privatised electricity assets would "likely have a negative impact on state finances in the long run".

The report was shortly reissued with a new title that read simply "Good for the state" and had a more positive view on the sale.

The opponents of privatisation, including the opposition Labor Party, seized on the note as evidence that privatisation would damage the state’s finances. They also accused the Baird government of pressuring UBS to alter the original report.

A NSW Parliamentary Inquiry is examining the events. Australia’s financial regulator, The Australian Securities and Investments Commission, has also been looking into the situation.

Baird nonetheless stuck by UBS as his advisers, and the incident didn’t affect the outcome of the election. That nice-guy image seemed to soften voters' view on asset privatisations and he was re-elected on March 28. The sale was on.

What’s up for grabs?

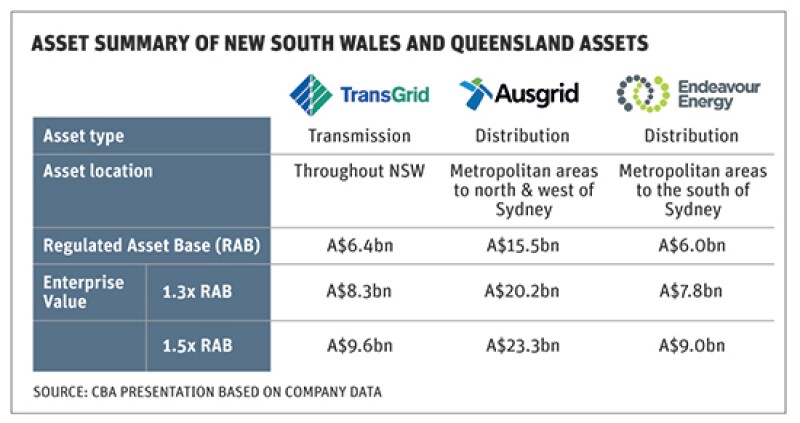

NSW is selling three businesses: a 100% lease of its transmission business, TransGrid; and 51% leases of two distribution operations, Ausgrid and Endeavour Energy.

According to Commonwealth Bank of Australia utilities analyst William Allott, listed Australian utility infrastructure stocks are currently trading on multiples of 1.3 to 1.4 times RAB (regulated asset base). That values TransGrid at A$9.6bn, Ausgrid at A$23.3bn and Endeavour at A$9bn at the upper end of multiples.

He says that suggests total proceeds for the NSW Government of A$18bn-A$21bn.

Allott says the assets are very attractive to a number of players, despite some recent tough regulatory decisions.

“Assets of this size and quality rarely come to market, and while there are question marks surrounding both the returns being achieved and the true value of the asset bases on which they are being achieved, we believe that international interest is likely to be very high.”

NSW decided to sell TransGrid first, followed by the other two assets. Because it was a 100%, the TransGrid sale “was more straightforward”, says one banker, who did not wish to be named but who is advising the NSW government on the privatisations.

No official announcement has been made about who is bidding and the exact formation of each consortium. But the investment banker advising the NSW government told Asiamoney that local media reports of the bidders were accurate.

The interested parties are divided into about seven consortia of large pension funds, Australian infrastructure players and a series of Asian players. Any foreign bidder will require approval for the purchase from Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board.

“There has been strong global interest,” the banker said. “We’ve had strong global interest, including from Asia. I wouldn’t limit that just to China.”

One consortium includes: major pension groups, such as Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, which has been investing in Australian infrastructure in recent years; global infrastructure investor Borealis, which is backed by one of Canada’s largest pension plans, OMERS; and AustralianSuper, the country’s largest superannuation fund.

A local Australian consortium is believed to combine Queensland Investment Corporation with IFM Investors, an infrastructure investor owned by a number of Australian superannuation funds.

Another global consortium includes Hastings Funds Management, ASX-listed Spark Infrastructure Group, Quebec’s Caisse de Depot, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and Wren House, the infrastructure arm of the Kuwait Investment Authority.

But perhaps the most interesting participants have been the Asian players, with billionaire Li Ka Shing’s Cheung Kong Infrastructure believed to be bidding.

One reported consortium includes China Southern Grid, China Investment Corp and Global Infrastructure Partners. China’s giant China State Grid is also believed to have teamed up with a unit of Australian investment bank, Macquarie Group. Other bidders reportedly include Singapore Power.

One bidder that had been public about its intentions was ASX-listed AusNet Services, which operates three energy networks in Victoria. As mentioned, Singapore Power owns 21% of AusNet and State Grid holds 20%.

The NSW Government called for expressions of interest in TransGrid in late June. The banker advising the government said that in late July the NSW government and its advisers were informing those who had been shortlisted and were asking for initial bids to be lodged. He would not comment on who had been shortlisted or the price.

A few days later, however, Singapore Power and China State Grid blocked the AusNet equity raising and forced independent director and TransGrid bid champion Tony Iannello from the board. Reports suggest the AusNet bid is in tatters.

'Unique' M&A

Neither AusNet nor Singapore Power replied to Asiamoney. In a statement to the Australian Financial Review, Singapore Power said: “There have been no arrangements for understandings between Singapore Power and State Grid on any of the resolutions put forward at AusNet’s AGM.” It also said Singapore Power did not submit an expression of interest in TransGrid.

But there is no doubt that State Grid will bid, and from a position of greater strength if AusNet has indeed been removed from the fray. One analyst who did not wish to be named said State Grid was favourite to secure TransGrid. “I’m not sure how you can expect them to miss out on an asset like this,” he said.

The analyst said State Grid wanted to deploy massive amounts of cash outside China. “They can also take a much longer time horizon in respect to turning a profit so they probably have an advantage over the listed guys."

Meanwhile, the consortia are busy talking to a range of banks, including global banks from North America, Asia and Europe, and the top four Australian banks, ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac.

One banker close to the possible raisings said that across the three NSW assets some A$20bn of debt will need to be raised. “These are very exciting times. There is a massive requirement of debt raising to be made across the three entities.”

The banker says it is a “unique M&A transaction” because all of TransGrid, Ausgrid and Endeavour’s debt is funded through the NSW State Government. “There is no third-party private sector debt into those entities,” he says.

He says all bidders are looking at debt packages and forming bank syndicates. “The structure still has to be decided. There is definitely a lot of engagement between banks and bidders at the moment.”

The acquisition will be financed by bank debt first “then pretty soon after the acquisition, the bidders will go out and raise long-term debt in global debt markets.”

Most will be trying to structure investment-grade financing, the banker says, given the volume of the debt and the future requirement to access global debt markets.

The TransGrid sales should be completed this calendar year, and the sale of Ausgrid and Endeavour would begin this year.

Despite the AusNet and UBS dramas, the outcome of the sales should be positive. Australia is an attractive place to do business with a stable economy. It is rare that three large electricity assets come on the market at the same time, which has allowed bidders to concentrate their resources in Australia.

A successful outcome in NSW is likely to add momentum to a privatisation of Western Australia’s energy assets. One banker said WA was already exploring privatisation.

“It’s pretty obvious,” he says. “They’re trying to work out what to do with their debt. There are probably not too many other solutions.”

It could also reignite interest in the Queensland privatisation down the track. In recent media reports the LNP’s new leader there, Lawrence Springborg, did not rule out a future privatisation if voters were comfortable with it.

“I think it is also fair to say that everyone will be watching with interest what happens in NSW in the future,” he said. “But I don’t see this returning to the agenda unless Queenslanders are comfortable with it. So as far as we’re concerned, we’re not taking that particular proposal to the next state election.”

The banker noted that in five years' time Victoria’s assets will have been privatised for 20 years, and South Australia’s for 15 years. NSW will have been finished and Western Australia is likely to have been done too. That will ratchet up the pressure on Queensland.

“They’ve got no option at the end of the day," said the investment banker close to the NSW process. "They’ll have to approach it differently with voters; but ultimately they’ll have to do it.”