There is an old Chinese saying, “you cast a brick to attract a jade”, which means to use a modest spur to encourage others to come forward with more valuable opinions or contributions. Many observers reckon something like this is happening in China’s attempts to internationalise its currency, the renminbi. RMB globalisation might now have reached the jade-attracting stage.

China's push to gain greater acceptance of the redback is not a recent phenomenon, but even as recently as last year many market participants were still clearly more focused on the question of how to access China’s onshore market than anything else — either by investing through the red-hot RMB Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFII) scheme or by setting up China-incorporated branches in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (FTZ).

A shift in thinking is now taking place. More and more, the view is gaining ground both within China and outside that RMB internationalisation should be more about China going out into the world to play a bigger role, and taking more responsibility in the international market to fulfil this.

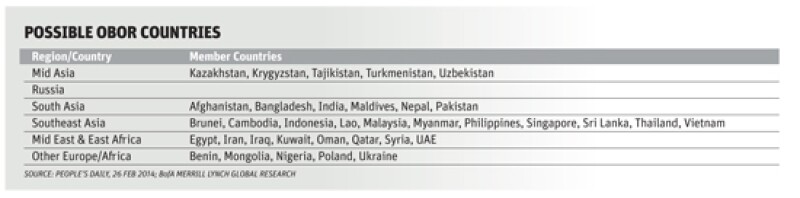

In late 2014 and so far this year, with the Chinese government starting to formalise its strategic initiatives into macro projects like the “One Belt & One Road” (OBOR) scheme, more sector-focused efforts like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), as well as specific technical initiatives like the offshore RMB clearing that will be implemented through the Cross-border Inter-bank Payment System (CIPS), the top-down change of tone in RMB internationalisation has caught investor attention.

“One Road”, a ground-based Silk Road for the modern age, aims to link China’s inland provinces with central Asia and Europe. “One Belt” is the marine equivalent and starts from China’s coastal region and goes all the way to Europe. The two are seen as closely linked with the future work of the AIIB, with many seeing that institution as the means to finance infrastructure throughout the regions encompassed by them.

It is obviously much more than that, however, since such initiatives also give China a valuable way to project its broader influence. And in all this, the opportunities for deployment of the renminbi will have big implications for the currency in the long run.

Hong Hao, managing director of research at Bank of Communications International, believes that as the AIIB has now signed up almost all the countries so far designated as offshore RMB clearing hubs (Canada is a notable exception), as well as far more other member countries than many had expected (57 members have been formally approved as founder members), it puts pressure on the post-Bretton Woods order of institutions like the World Bank Group — as well as the global primacy of the dollar.

“As the AIIB will raise some of its capital by selling RMB-denominated bonds to invest in infrastructure in the less developed areas of the world, member countries of the organisation will have the opportunity to become offshore RMB centres," says Hong. "Therefore it will increase the RMB’s prominence globally and sidestep the dollar."

Hong reckons that this, accompanied by the continuing opening of China’s capital account, will see the country gradually move away from its traditional ways of foreign exchange reserve management, mostly by buying US Treasury bonds, to investing some of its reserves in RMB in overseas infrastructure. Recent data from the US Treasury indicated that Japan was now the largest holder of US government debt, after China reduced its investments by about $49bn in the last year.

“It is a significant change," says Hong. "As the petrodollar is dying, and the dollar recycle loop from China’s current account to US Treasury bonds is about to slow, the situation for the dollar and the US Treasury appears delicate for now."

Bank of America Merrill Lynch echoed this view, noting in a March 16 report that OBOR would essentially switch a portion of China's FX reserves from US Treasuries into emerging market direct investment and debt.

And a recent survey conducted by HSBC and Central Banking Publications showed expectations of a striking rise in adoption of the RMB in central bank reserves. The average view of some 51 reserve managers responsible for $2.7tr was that the RMB might account for 10% of global reserves by 2025. The current level is not publicly known, but the same managers said that it might hit 2.9% by the end of 2015.

“Reserve managers seem to be caught between a rock and a hard place, with deep concerns about both negative rates in euro and the prospect of rising rates in the USD, a currency which by default has become increasingly pre-eminent as a reserve currency,” comments Christian Deseglise, global head of central banks and reserve managers at HSBC at the time of the survey.

The beauty of CIPS

One initiative enjoying less widespread attention but which arguably could prove to be a more magnificent tool for RMB internationalisation is China’s upcoming Cross-border Inter-bank Payment System (CIPS). According to two market sources, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) is aiming for October 8 for the system to go live.

One of those sources says that CIPS will be a parallel infrastructure alongside the existing onshore China National Advanced Payment System (CNAPS) to allow cross-border RMB payment and settlement from anywhere in the world into China.

Seven international banks — ANZ, BNP Paribas, Citi, DBS, Deutsche Bank, HSBC and Standard Chartered — are among the 19 firms to have been selected for first stage testing of CIPS. This means that, for the first time, non-Chinese banks will be allowed to have direct access to China’s onshore liquidity pool for offshore RMB transactions.

“For the foreign banks like BNP Paribas, the beauty of CIPS is that it actually creates a complete level playing field with Chinese banks within the international space,” says Julien Martin, head of the RMB Competence Centre at BNP Paribas.

Currently, the clearing bank model dominates offshore and cross-border RMB clearing, with official Chinese clearing banks in each RMB hub having direct access to CNAPS via their onshore headquarters, (except for Hong Kong's RMB clearing bank, Bank of China Hong Kong, which has its own direct access to CNAPS).

The downside for non-clearing banks is that in all hubs apart from Hong Kong — where the market is sufficiently developed to make using a correspondent banking model a viable alternative to using the clearing bank — non-clearing banks need to hand over precious data and the control of a transaction to the clearing bank.

“It means the clearing bank is concentrating all the flows from one centre into China," says a banker at an international bank. "We are effectively transferring our responsibility for payments to a third party, the clearing bank. As a result, we also completely disappear from the [clearing] statistics.”

On the surface, therefore, CIPS appears to be an example of China giving more access to overseas participants. But viewed another way it may be more aligned with China's going-out strategy. Through CIPS, all offshore RMB centres will have a uniform method of directing worldwide payments into China. But it won't stop at that.

“The way that the PBoC is segregating offshore payments [using CIPS] from the onshore ones [using CNAPS] is very smart," adds Martin. "Not only it will limit any risk that cross-border payments may bring into the local banking system, but in the long run CIPS will be set up to deal with all CNH payments, including offshore to offshore, thus allowing greater convergence between onshore and offshore markets before they eventually merge.”

By introducing CIPS to centres where a local RMB market is not yet developed, or potential hubs where there are no real flows, China is offering a more accessible system for RMB payments that will effectively use the assistance of global banks, which will be able to establish links with China wherever they have a presence. And there are important advantages for the Chinese banks, too.

“From the point of view of the current Chinese-appointed clearing banks, it does create more competition," says Martin. "But it also gives them a system that they can use everywhere and facilitates their services on their way to going global."

Some are so confident of the system's advantages that they foresee an even bigger role for CIPs in the very long term, arguing that once it is operating well and has been accepted by the market, there is no reason why it could not include clearing in other currencies.

More outbound channels

If these blueprints seem designed more to satisfy mid-to-long term targets, there are also plenty of more immediate going-out policies that have been widely implemented. A gradual but steady approach toward opening cross-border investment flows is being taken by China’s top industry regulators.

A series of moves aiming at further loosening the country’s capital account restrictions has been kicked off by the central bank. Among these was the PBoC's move in November 2014 to issue a set of rules for the RMB-denominated qualified domestic institutional investor (RQDII) scheme to facilitate offshore RMB investment activity by domestic institutional investors, in a step seen as complementary to the existing RQFII scheme.

Jeffery Peng, head of investment products and services at UBS (China), points out that as the number of China’s high net worth clients grows and as these become more sophisticated investors, the push on RQDII from the regulator will suit well their need to be more actively involved in the international capital markets.

“The fundamental motivation of investing through RQDII is the rising requirement for truly diversified asset allocation from Chinese investors,” says Peng. “They don’t only have their eye on returns but also on how to balance the investment risks. Although they can invest in different asset classes in China, at the end of the day these are still assets from the same basket.”

UBS (China) debuted in the RQDII market at the end of last year, launching a fund investing in high yield credit-linked notes issued in North America with an estimated return of around 6%. Peng notes that by being RMB-denominated, RQDII has already managed the FX risk for investors. It can therefore be a more comfortable way for investors to test the water in the overseas market without worrying about extra losses as a result of exchange rate movements.

“As the government has been allowing more CNY volatility within its daily trading band, it’s a good time to purchase products like RQDII," says Peng. "In turn, the expansion of capital out flows will further help the RMB usage globally, which is in line with the government’s continuing effort to promote RMB internationalisation."

The PBoC’s intention in encouraging more outbound investment was also reaffirmed in March 2015 by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), which released a set of guidelines for local mutual funds to participate in the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect. This meant that existing and new funds were allowed to expand their investment scope into Hong Kong stocks without having a QDII licence and quota.

The effect was rapid. Hong Kong equity indices broke records and mainland purchases of H-shares regularly exhausted the southbound daily quota of the Stock Connect.

Charles Li, chief executive of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEx), wrote on April 9 that the real and lasting meaning of the Stock Connect was to enable Chinese investors to internationalise their asset allocation in order to grow their wealth over the long term.

Lu Wenjie, H-share strategist at UBS Securities, echoes Li’s view, saying that allowing such funds to enter the Stock Connect without a QDII licence would add more diversification in China’s onshore fund products, especially for medium to small sized firms. As a result, it would entice more investors to look overseas.

Describing A-shares as "a bull market without growth" and H-shares as "a value market without liquidity", Lu reckons the additional liquidity from mainland investors could make a big difference to H-shares, given that the current daily turnover of the Hong Kong market is only one tenth of A-share volume.

Just days after CSRC's move, the China Insurance Regulatory Commission (CIRC) — watchdog of China’s insurance sector and seen as a comparatively conservative regulator — announced a set of relaxations on overseas investment rules for domestic insurance funds.

Under the new rules, CIRC not only allowed insurers to invest beyond Hong Kong and into 45 national or regional markets, but it also lowered the minimum credit rating requirement of bonds that they invest in, from BBB to BBB-. Additionally, insurance funds have also been given the green light to invest in Hong Kong's Growth Enterprise Market (GEM).

The insurance industry has benefited from expanded investment opportunities, with average yields of 6.3% in 2014 and overall profits doubling for the sector, CIRC said in January.

The principal motivations behind the changes are to encourage insurers to diversify their portfolios and also to help prepare the way for the overseas investments that will be required to finance projects under the "One Belt, One Road" initiative.

TF Cheng, head of Greater China Business at BNP Paribas Investment Partners, sees CIRC’s new move as a milestone in the journey of China’s onshore practitioners into the international stage.

“CIRC’s newly revised regulations regarding insurers’ overseas investment is in line with China’s entire go-out strategy," says Cheng. "Liberalising the rules is in order to get the onshore financial institutions ready for the potential investment opportunities that RMB internationalisation will bring with it."

Cheng notes that the move can be seen as giving a final official passport for Chinese insurers to have more interaction with the global market.

“From the massive global market, Chinese insurers may find a good match either in duration or return for their onshore long-term liabilities,” he says. “Now is a good time to invest in European assets, given that the market is expected to take off gradually due to quantitative easing. The Asian credit market in general can also be a good allocation for them.”

CIRC data shows that the total outstanding overseas investments from Chinese insurers reached $24bn by the end of December 2014. This was up almost 150% in two years, but it still only accounted for 1.44% of all insurance sector assets in China. Hong Kong was the top target market, while equities and bonds were the main investment tools, followed by real estate.