Watching China attempt the manifold manoeuvres required to create a fully functioning and modern financial economy is like watching a juggler at work. Instead of balls or clubs, though, Beijing is employing a dizzying array of measures designed to open its capital account, boost the global use of its currency, the renminbi, and channel more local and foreign capital into debt products and equity offerings.

Each of these overlaps and interlinks. And as long as all the balls are in the air, everything runs seamlessly. But with one slip, the entire show could come crashing down.

To the current crop of Party leaders, opening the capital account more fully while boosting the flow of RMB in global trade is deemed vital to long term economic credibility and the nation’s self-esteem.

“China's financial and capital markets reforms are one of the [country’s] top agendas, and will continue in order to achieve the ultimate goal of capital account liberalisation and full RMB convertibility,” says Candy Ho, global head of RMB business development at HSBC.

Jonathan Anderson, a partner at Hong Kong-based consultancy Emerging Advisors Group and a former global emerging market economist at UBS, believes that having an international currency is deemed internally vital to China’s meteoric rise. “After the financial crisis, they realised that holding so many US dollars just added more risk and external exposure,” he says.

SDR appeal

How fast and how fully these ambitions can be achieved is open to debate. Take the opening of the capital account, a subject seen as central to the Party’s aim of reforming still-underdeveloped financial markets. In its Asia Economics Monthly report published on April 16, Deutsche Bank pointed to a government pledge to make the currency convertible in 2015.

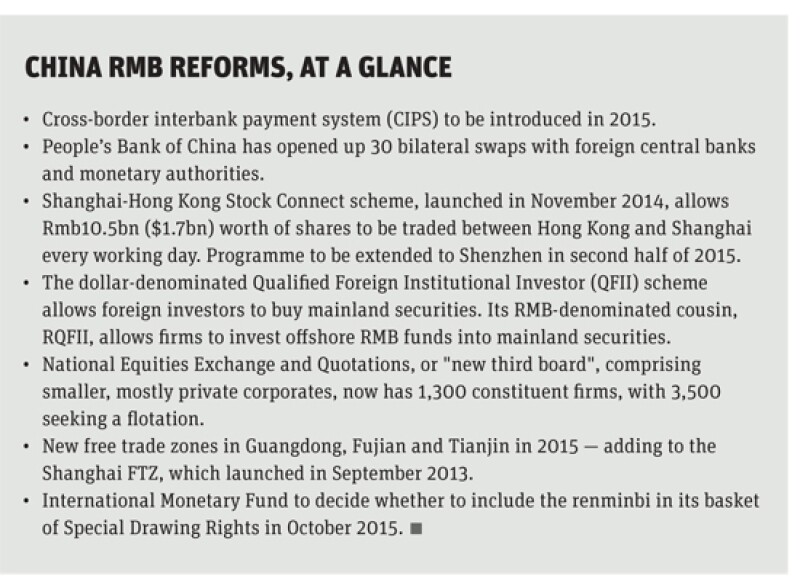

To those that only see the RMB becoming fully convertible years down the line, this may seem unlikely. Yet from one perspective, this stated ambition makes good sense. In October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) will decide whether to include the RMB for the first time in its basket of Special Drawing Rights (SDR). The review will not take place again this decade, and the Party clearly does not want to wait another five years.

Inclusion of the RMB in the SDR basket alongside the likes of the US dollar, euro and Japanese yen would give IMF member states greater exposure to China's currency in their reserves. “Demand for the RMB and for RMB-denominated investment products would likely increase, and drive further the opening of the onshore capital markets for reserve asset accumulation,” notes HSBC’s Ho.

Shiming Tan, Asia Pacific head of renminbi products at Citi, said he believed inclusion in the SDR basket would “establish the RMB as an important reserve currency. It will help convince global central banks to add the RMB to their portfolios, which will mean a step-up in global recognition of the currency.”

In its April report, Deutsche Bank pointed to a number of significant reforms expected in the second and third quarters of 2015, paving the way for inclusion in the basket. These, it said, would be likely to include revised regulations on exchange controls, greater liberalisation of the bond markets, and permitting individual investors in China and overseas to make cross-border investments.

Membership of the SDR offers practical advantages, but also guarantees Beijing some bragging rights. As well as smoothing China's integration path with global capital markets, it would, in Beijing’s eyes, amount to wider recognition of China's development and its importance to the international financial system.

Yet the currency isn’t in the IMF’s basket of elite currencies just yet, and its inclusion is far from a foregone conclusion. To secure access, a country must be integral to all aspects of global trade, while possessing a currency already deemed widely traded or, to use the IMF’s language, "freely usable".

“China easily passes the first criterion, as it ranks second in global goods and services exports, but the second is debatable,” notes Donna Kwok, senior China economist at UBS.

Many, however, expect the IMF to massage its rules and to make an exception for China. The world’s coming economy has already fostered a host of offshore RMB centres, from Hong Kong and Singapore to London and Frankfurt. Foreign corporates have raised debt in the currency, while institutional investors' appetite for assets held onshore in RMB grows by the year.

“China has made great strides in ticking the second box in the past five years,” adds UBS’s Kwok. The renminbi recently ranked as the world’s second largest trade financing tender, according to data from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (Swift), and the most commonly used transaction currency.

Intricate links

Others wonder whether the push to become an official SDR currency is as important as it seems. Beijing’s love of misdirection means that when a specific reform is trumpeted, the real one is often happening elsewhere. China’s leaders also like to draw attention to a simple target (the basket being a prime example), in order to camouflage the complexity of their ambitions. This may well be happening here.

To many, the RMB’s inclusion in the SDR is merely a catalyst for a series of interlinked financial-sector reforms, including interest-rate liberalisation and the opening of the capital account. The governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), Zhou Xiaochuan, has talked recently and openly about the importance of liberalising the capital account and potentially eliminating deposit-rate controls.

Indeed, the PBoC has, after years of accretive development, become one of the country’s most radical institutions, opening up bilateral swaps with more than 30 central banks and monetary authorities. The central bank has spoken of its desire to launch a cross-border interbank payment system this year, designed to improve the efficiency of transnational RMB payments, while making the currency more competitiveness in terms of trading time, language, risk and liquidity management.

A bolder and more expansive regulatory environment is also designed to help mainland lenders in their own efforts to internationalise, and to support the global ambitions of Chinese firms, from conglomerates to insurers and infrastructure specialists to industrial giants.

“Chinese banks have aggressive expansion plans overseas, as [rising] cross-border loans net outflows showed in 2014,” said HSBC’s Ho. “Banks are also now encouraged to go abroad to seek new avenues of growth and support Chinese companies’ overseas expansion.” As use of the currency grows, with local and foreign firms extending loans and issuing bonds denominated in renminbi, hedging costs should decline, along with the spectre of foreign exchange mismatches and financial risk.

Thus, the opening of China’s capital account, while important, is a single moving part in a far larger and more complex reform picture. For it to work seamlessly, all the other pieces need to operate precisely as planned.

“Progress in one area of financial reform dovetails intricately with progress in other areas of financial reform,” says UBS’ Kwok. “Many, including those in the PBoC, believe that these reforms are critical to increasing capital allocation efficiency, and that opening up the financial sector could intensify pressures to accelerate domestic reforms.”

True intentions

Two further questions arise, which will come to define how the world views China over the next 20 to 30 years; does Beijing actually want a fully open capital account, or indeed a truly global currency?

Here, opinions diverge widely. To UBS’s Kwok, “China’s goal is eventual full capital account convertibility, which one day will see the full convergence of the onshore and offshore RMB market.”

Others aren’t quite so sure. Emerging Advisors Group’s Anderson comments: “From a pure macro point of view, China isn’t quite sure that it wants a fully open capital account. The capital account isn’t quite as closed as it used to be but it’s still pretty closed. I don’t think anyone in China is that interested in a full opening while they are trying to deleverage the economy.”

Beijing’s true intent, he argues, is to increase foreign investment in the domestic equity market, while triumphantly securing admittance to the SDR basket.

Others wonder whether China’s leaders are willing to embrace the sort of volatility that usually accompanies a switch from a closed to an open capital account. Anderson points to the travails of Russia, which has one of the most open capital accounts in the emerging world.

“Every few years the oil price tumbles, Russia’s economy collapses, and everyone sends their money overseas, draining central bank resources,” he notes. “Even Switzerland has moved away a little from having too much capital account flexibility.”

Then there’s China’s currency itself. Many remain in the dark about the renminbi’s long-term prospects. At present, the assumed narrative is that in time, the current, divided onshore (CNY) and offshore (CNH) currencies will merge, creating a single unified Chinese tender available to use, trade, and settle, from Beijing to Bogota.

Analysts and media willingly perpetuate this view. When a European capital announces the formation of a new RMB hub or a central bank in Africa or Asia rolls out a bilateral currency swap, it makes a splash on the business pages. And there’s no doubting China’s determination to encourage the use of its currency to settle cross-border trades. To Citi’s Tan, the benefits of a stronger international currency include “reducing reliance on the dollar, helping carry forward China’s financial development agenda, and further integrating the RMB into the global monetary system … increasing China’s presence on the global stage.”

Yet the currency remains something of an afterthought in key arenas such as the global bond markets, and is unlikely to challenge the US dollar (or even the euro or yen) any time soon. “We are still quite a few years away from the Rmb becoming the world's reserve currency,” says Jonathan Woetzel, a director and China expert at McKinsey Global Institute.

Global or not?

Others wonder whether Beijing is indeed serious about disseminating its tender across the globe. The idea of Chairman Mao’s face in the wallet of every global traveller, oil trader or portfolio investor may inflate the ego of any patriotic mainland national, and hand Party leaders more control over its own economy and that of the world. But that would spawn greater responsibility, raising the question of whether China really wants a currency that it has to share with the world (and which it may not entirely be able to control).

Many in power in Beijing still associate the national dream with the creation of a currency used solely onshore (a Chinese currency for the Chinese people), and view the prospect of a truly international renminbi with deep suspicion.

“There is no long-term plan to have a globalised currency,” says Anne Stevenson-Yang, co-founder of independent Beijing-based consultancy J Capital Research. “Rather, there is a long-term plan to continue the investment-driven expansion, and this is one way to accomplish that now. Don't think for a moment that trade surpluses would be sacrificed to currency globalisation.”

Besides, for the time being, most investors are interested in far less abstract musings. The past year has seen a slew of major reforms by Chinese financial and securities regulators. The Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect scheme — which allows certain Hong Kong listed stocks to be traded in Shanghai and vice versa — now allows up to Rmb10.5bn ($1.7bn) worth of shares to be traded between Hong Kong and Shanghai every working day.

The programme began slowly in November 2014, but picked up pace in March and April, pushing both Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index and the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index to seven year highs. A similar two-way trading link tying Hong Kong with the southern city of Shenzhen, home to China’s second bourse, is set for launch in the second half of the year.

Other reforms are also helping boost stock prices across greater China. The RMB Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFII) scheme allows foreign investors to buy mainland-listed securities. Beijing is also pushing forward with the formation of three new free trade zones in Guangdong, Fujian and Tianjin, following the launch of the Shanghai FTZ in 2013. In March 2015, CCB International Asset Management, a unit of state-run China Construction Bank, launched a London-listed exchange-traded fund, the first European ETF to invest directly in China’s money market.

There is also the National Equities Exchange and Quotations (NEEQ) index, also known as the "new third board", which is set up to suck local and foreign capital into smaller, fast-growing and mostly privately owned mainland corporates. More than 1,300 firms, many without audited financials or a profitable track record, had listed on the over-the-counter equity exchange by the end of 2014, with another 3,500 seeking a flotation, mostly with the aim of listing over time in Shanghai or on Shenzhen’s Nasdaq-style Growth Enterprise Market.

“The key now is to open up domestic markets to the rest of the world in order to increase two-way portfolio investment flows,” notes HSBC’s Ho. That is likely to generate more volatility, forcing regulators to implement key foreign exchange reforms, from widening the daily US dollar-renminbi trading band, to making dual-currency mechanisms more market-oriented and transparent.

“All these schemes,” says UBS’ Kwok, “are part and parcel of China’s toolkit for gradually opening up its capital account with the outside world, [and] making its onshore capital markets increasingly linked to offshore capital and financial markets.”

Home help

This more welcoming approach to international capital is no mere accident. Beijing rarely makes such decisions without an end in mind. For the renminbi to be used internationally to settle transactions, global traders and investors must be able to gain access to broad range of financial assets denominated in that currency. Hence the push to drive more foreign institutional capital into blue-chip and smaller mainland securities, and onshore-listed debt products.

To create a more readily used currency in the international arena, notes Citi’s Tan, a country “must have broad, deep, and liquid financial markets. I expect that China will continue to further promote two-way capital account flows.”

It is, of course, possibe to take a more sceptical view. Just as Beijing rarely pursues a fuzzy objective, it tends to make decisions that act to the system’s best benefit. To some, the opening-up of China’s securities markets reflects the Party’s desperation to inject more capital into the more productive corners of a flagging economy, create new funding avenues for capital-starved corporates, and deal with the nation’s mounting debt problem.

In a March 23 report entitled "China’s Currency Conundrum", analysts at J Capital wrote: “The authorities are doing everything in their power to engineer a sustained bull market and to formalise local-government debt, by allowing local authorities to issue public bonds. Chinese regulators are also trying mightily to redirect investment capital into the [domestic] A-share market.”

Each of the moving parts of this picture, from boosting the use of a still largely unknown and unused offshore currency, to reforms designed to turn foreign investors into avid collectors of Chinese stock, would be tricky for any emerging market, whatever its size and clout, to keep track of. Perhaps only a country that remains in many ways financially isolated from the rest of the world could hope to pull it off.