Japanese banks are back as the world’s largest international lenders, a status last attained during the doomed asset bubble of the late 1980s. As well as dominating the league tables for cross-border lending, the three Japanese megabanks have been snapping up assets from shrinking European and American rivals in a concerted drive to expand overseas.

Could it end in tears again? The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel has a chart showing foreign lending by Japanese banks rising vertiginously like the Matterhorn from 1984 to a peak of 36% of all global cross-border claims in 1989. It then plunges off a precipice, as the collapse of the asset bubble triggered a severe banking crisis in Japan, and does not hit bottom until 2007.

“The situation now is completely different to the 1980s, which was before the BIS era of tighter capital regulation,” points out Hideyasu Ban of Morgan Stanley MUFG. “Basel 1 was introduced in the early 1990s and came in response to very aggressive Japanese lending. Japanese banks didn’t care about their overseas profit margins; in the West it was called ‘kamikaze lending.’

"This time around the banks face capital constraints and limited demand in the domestic market. They are being forced to look overseas.”

Abenomics — the economic policies of prime minister Shinzo Abe’s government — has fuelled a stock market boom in Japan but only a fairly modest boost to borrowing demand, with domestic loans still accounting for only 70% of total deposits. Inflation has turned positive, which is what the Bank of Japan (BoJ) wants, but deposit growth perversely is still increasing, observes Nana Otsuki, banking analyst at Merrill Lynch Japan.

Meanwhile interest rates are barely positive, thanks to quantitative easing coupled with intense competition among the banks. “The net interest margin is really disastrous,” she remarks.

“Margins are negligible, and since plain vanilla lending is leading to low digit return on equity, the banks are trying to capture investment bank or other fee-based income,” adds Ban of Morgan Stanley MUFG. “Going overseas is really to make up for the low profitability of the domestic lending operation.”

Atul Sodhi, head of Asia Pacific loan syndication, debt optimisation and distribution at Crédit Agricole, agrees it is a rational outcome. “The immediate prospects for Japanese economic growth are still uncertain, and Japanese companies have to look offshore, either expanding organically or through acquisitions.”

It’s a similar story for the banks. “However, liquidity in Japan is very strong, partly because of the high savings rate, and partly because of the increased monetary easing by the central bank," adds Sodhi, who also chairs the Asia Pacific Loan Market Association. "So they have liquidity and appetite. Put all this together — their clients going overseas, low growth at home, strong liquidity in the home market — where do you go? You have no choice but to go overseas.”

Domestic pressure

At Mizuho Financial Group, Japan’s number two banking conglomerate, overseas operations accounted for 77% of income from customer groups in the final quarter of 2014. “The growth of our domestic lending is limited, while overseas lending is steadily expanding. It is a fact that interest-rate profit is ultra-thin,” concedes Mizuho group spokeswoman Masako Shiono.

The BoJ has more than doubled the monetary base from ¥120tr ($1tr) at the start of 2013 to ¥290tr, and next fiscal year it may exceed ¥400tr. The BoJ does this mainly by buying up vast quantities of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) from the Japanese banks and insurance houses. Mizuho alone cut its JGB holdings by one third since March 2013, to ¥20.5tr at the end of December 2014.

A large chunk of the JGB sale proceeds lies parked in excess deposit accounts at the BoJ, where it earns 0.1% interest. Japan’s three megabanks, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG), Mizuho, and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (SMFG), together had almost ¥100tr in these "Complementary Deposit Facility" accounts at the end of last year. SMFG’s balance at the BoJ exceeded its total lending to domestic corporates.

“That’s why the Bank of Japan is doing quantitative easing on such a scale, because they know the money multiplier in Japan is so low,” says Graeme Knowd of Moody’s Japan. “As long as some of the money leaks out into the real economy, that’s a good thing. The BoJ would like the banks to redeploy the money, which they are doing by putting it overseas.”

Knowd cautions against being mesmerised by the banks’ ocean of liquidity into assuming it can be readily deployed into foreign lending. “You need capital to make a loan. JGBs were zero risk-weighted. You didn't need to look at them. You can't change all of your JGBs into loans overnight; the banks don't have the capital.”

Knowd explains how BIS capital restraints can work in practice. “The banks used to hold 20% of their balance sheet in zero risk-weighted JGBs. So they held zero capital against that. If half were to go into lending, you would need to set aside at least 8% of that additional lending as extra capital.

"Let’s say you have a ¥200tr balance sheet. Ten per cent of that is ¥20tr, so you would need an extra ¥1.6tr in extra capital just to hold your capital ratio steady. Even if you find the loan outlets, you can't just switch overnight.”

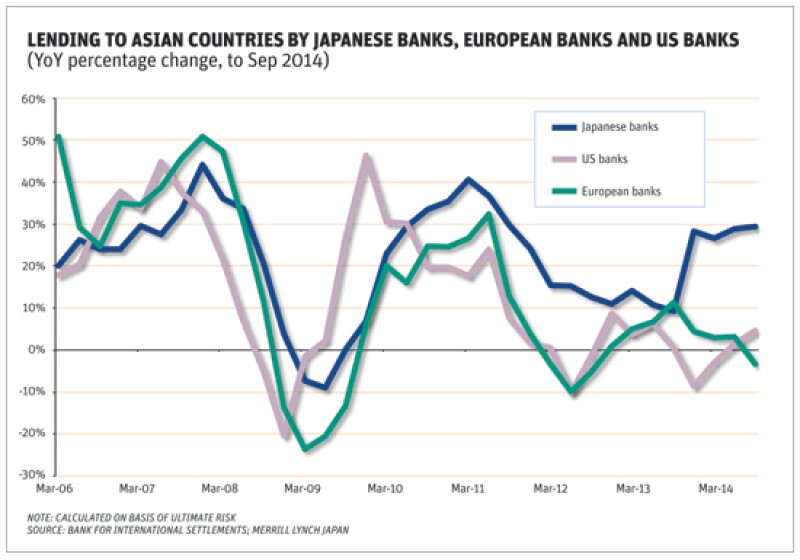

Otsuki of Merrill Lynch nevertheless points out that Japanese lending to the rest of Asia has surged since April 2013 when Haruhiko Kuroda took over as governor of the central bank. “This means that BoJ monetary loosening has clearly and significantly affected the overseas lending attitude of Japanese banks. It’s really strong at this moment in spite of the hurdle of having to swap yen into foreign currencies.”

Asia is a favoured investment destination for Japanese corporates and looms large in the strategic plans of all the megabanks.

Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, the smallest of the three, aims “to establish an Asian franchise that equals our Japanese franchise,” enthuses Kenichi Hosomi, director of planning at its international banking unit. Being “Asian-centric” is natural for SMBC, he adds, since the Asian market “is geographically and culturally close to Japan and has a great growth potential.”

Mizuho, says Shiono, is also vying to be “the top financial group” in Asia, where so many of its Japanese customers do business.

Spending spree

Japanese banks have been greatly helped in their overseas advance by the retreat of Western rivals wounded by the global financial panic of 2008 and the European sovereign debt and banking crisis that began in 2010. Both left the Japanese banks relatively unscathed. One reason why the megabanks recently reported high profits is writebacks of bad loan provisions made in the wake of 2008.

At the height of the global financial crisis, the US government came to Citigroup’s rescue with a $45bn equity investment. Soon after, Citi began selling its Japanese assets: its 64% stake in Nikko Asset Management to Sumitomo Trust & Banking for ¥75.6bn, its domestic Japan securities business Nikko Cordial to SMBC for ¥774.5bn, and NikkoCiti Trust to Nomura Trust & Banking for ¥19bn.

(American taxpayers later made a $15.5bn profit on the sale of the government's shares, and last year Citi agreed a $7bn settlement of claims related to the 2008 crisis with the US Justice Department.)

On Christmas Day 2014, SMBC said that it was buying the retail banking business of Citibank Japan for about ¥40bn and merging it with its private banking unit, SMBC Trust, the new name for Société Générale’s former Japan private banking business, which SMBC in turn had acquired from the French bank in 2013.

This April, Citi said that Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank was buying its Diners Club credit card business in Japan for about ¥40bn.

Citi’s sell-off pales beside that of Royal Bank of Scotland, 79%-owned by the UK government since a 2008/2009 rescue that ended up costing £46bn ($68.6bn). RBS has been steadily dismantling its global empire ever since.

In 2010, Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ said it would buy RBS's project finance portfolio for Europe, the Middle East and Africa for £3.3bn. Two years later, RBS agreed to sell its $7.2bn aviation leasing business to SMFG and Sumitomo Corporation.

This February, Mizuho announced it was buying a North American corporate loan book for about $3bn from RBS. April saw another trumpet blast from Mizuho, with the hiring of RBS debt capital market and corporate finance teams, about 130 bankers in all, for Mizuho’s expanding operation in New York. Mizuho’s staff haul includes Jennifer Powers, former head of DCM at RBS, and Victor Forte, who was co-head of global syndicate.

John Koudounis, CEO of Mizuho Securities USA, tells Asiamoney that Mizuho is also looking to cherry-pick RBS staff in equity capital markets (see interview). The hires from RBS received no garden leave but promptly decamped from the bank’s large North American office and trading floor in Stamford, Connecticut, to Mizuho’s offices in New York.

RBS disposals in Asia Pacific have nearly all gone to local banks. ANZ in 2009 agreed to pay $750m for RBS retail, wealth and commercial businesses in Singapore, Indonesia and Hong Kong, and RBS wealth, commercial and institutional businesses in Taiwan, the Philippines and Vietnam. One year later RBS transferred, for free, its retail and commercial portfolios for Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen to DBS of Singapore.

DBS gained 25,000 customers in three key Chinese cities as well as some RBS staff. “We didn't invest a single cent. RBS wants to exit, we want to accept, it’s just as simple as that,” the CEO of DBS in China said at the time.

CIMB of Malaysia snapped up in 2012 the cash equities businesses of RBS in mainland China, Hong Kong, India and Taiwan, and most of its ECM and mergers & acquisition operations in Australia, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand. RBS said the sale price would cover only part of the closure costs.

“Until three months ago I could see RBS in a fairly high position in the Asian league tables. Now they are closing down everything. They are selling their branches, selling their books, they are just out of here,” a senior loan banker tells Asiamoney. “In Hong Kong they may keep the licence but they will be doing close to nothing. They will just be serving companies with a UK franchise that do some business in Asia.”

Not forever

There is a notable lack of schadenfreude from Japanese banks at this favourable turn of fortune’s wheel. Instead, there is a note of sober apprehension.

“The retreat or withdrawal by European banks seems to be temporary,” says SMFG spokesman Takashi Morita. “The major European banks have raised their fully loaded common equity tier one ratios to more than 10% through reducing their risk-weighted assets and increasing capital. As a result, their financial soundness is improving.

"Although there have been business disposals, responding to recent global discussions on strengthening financial regulations, it is unlikely that European banks will face further pressure to compress their assets rapidly in the immediate future.”

Low economic growth throughout much of Europe is again pushing European banks to expand their business in growing emerging markets, Morita believes.

One chink in the Japanese armour is dependence on wholesale funding and the swap market to finance foreign currency lending. A similar funding vulnerability struck down European and American banks that engaged in reckless lending in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis.

SMFG is the most exposed of the three megabanks, with a loan-to-deposit ratio of 160% for its international business. This is what makes the pending acquisition of Citi’s loss-making retail bank in Japan so attractive. Roughly ¥1tr worth of Citibank Japan’s ¥2.44tr of total deposits are in foreign currencies. By acquiring these deposits, SMFG can lower its foreign loan-to-deposit ratio to almost the same level as Mizuho.

Interview: John Koudounis, CEO of Mizuho Securities USAPursuit of expansion at all costs is what brought 300 year old Royal Bank of Scotland to its knees in the global financial crisis. The £58bn doomed takeover of Dutch rival ABN Amro in 2007, just as global storm clouds were gathering, was arguably the worst M&A deal ever. Ironically, it prompted John Koudounis, now CEO of Mizuho Securities USA, to leave ABN Amro. Mizuho this year bought a North American corporate loan book from RBS and has been cherry-picking RBS staff in the US. Asiamoney spoke to Koudounis about the firm's strategy. What will you do with your 200 new corporate customers as a result of this acquisition? “We bought the loan book not just because we wanted more loans but because we wanted to capitalise on the assets through our already very strong capital markets business. It only started seven years ago, but especially in debt capital markets we’ve gone from a non-existent business to what at times is among the top 13, or higher, underwriters in the US. This deal puts us forward by about two years in our goal of becoming one of the top 10.” So you want to underwrite their debt? “Yes, most are potentially debt-issuing clients and they have been issuing debt with RBS in the past. Having said that, I am very familiar with the portfolio, because I also worked at ABN Amro. RBS took over ABN Amro and there is a lot of legacy, not just loans but people and DCM too. The way you monetise the asset is by doing a lot of the capital markets fees associated with the relationships of these corporates.” In a nutshell, you bought from RBS a corporate loan book for North America and hired their DCM and corporate finance teams in the US… “Amongst other things. We’re also looking at possibly hiring their equity capital markets, commercial paper and high-yield teams.” Is this part of a global drive by Mizuho to bulk up in DCM outside Japan? “I joined Mizuho seven years ago from ABN Amro, when RBS acquired it. One of the first things I started was capital markets in the Americas for the institution. We had not led a deal before I got here, and now we are leading several deals a week at times, and we’re jumping up the league tables, and it has become a very profitable area for us. "Just by leveraging the bank’s balance sheets and relationships of corporate clients that the bank has been lending to for several years. Not just Mizuho, but its predecessor banks, IBJ, Fuji and Dai-Ichi Kangyo. I am talking mainly about Fortune 100 American corporates that we lent to.” Mizuho is often considered the leading debt house in Japan. Is it DCM prowess that you want to be known for in the US? “Traditionally, that has been our strength, but we have also shown that we are capable of leading some very large transactions. We were one of three lead managers — with JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo — in financing the $66bn acquisition of [Botox maker] Allergan by Actavis. We providing a third of the $45bn bridging loan, and were the only Japanese bookrunner when Actavis issued $4.2bn of common stock and $4.2bn of convertible prefs. "We followed that a week later with a $21bn bond offering for Actavis, which was the second largest bond offering in the history of the market. So we have been active lately in both the bond market, but have also started to pick up in the equity market too. I have hired some key new people in equities, and want to hire a lot more.” Is what you are doing illustrative of how Mizuho intends to build a global investment banking business? “We’ve already shown that we’re a global player by being pretty successful in the United States. Already in certain markets we’ve entered, like debt, I think it's hard to find a global bank leaping up the league tables in the last five to ten years apart from ourselves. Most other financial institutions have been consolidating and shrinking. "I think it's a great story. In spite of what the rest of the world is doing, we’re growing, and actually doing a really good job at it, but at a steady pace.” So far Mizuho doesn't own a US deposit-taking institution… “That is something we are constantly looking at.” How is Abenomics helping your business in the US? “If you look at the market holistically, where flows are moving, Japan has to buy outside of Japan. They have to increase their yields. Where JGBs are trading there’s just no yield now, and as they continue to try get out of a deflationary environment, they are going to have to continue to reach for yield. "You are starting to see that in the new allocations for equities by the GPIF, the largest pension fund in the world. In the international equity arena the US is the biggest beneficiary of that. You see it also in what we did. We can allocate our money and purchase whatever we want. We have decided to do this as a global institution here in the Americas.” Doesn't capital limit how much Japanese banks can lend abroad? “It’s all part of the regulatory environment we live in. But the reality is they do have more cash, and they could allocate capital to the United States if they choose. A lot of what regulators are trying to do here is to ring-fence foreign banks, just in case there is another crisis. That’s a big part of all the regulatory effort here, to increase all the capital for banks doing business in the Americas. "A lot of banks, not just Japanese, are making decisions whether they want to go big or go home, in terms of doing business in the United States.” |