A period of strong growth in the 1980s and 1990s saw Taiwan's burgeoning manufacturing industry propel it to be one of the most developed economies in Asia, alongside Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea — the other Asian Dragons.

Its outperformance saw a dip at the turn of the millennium, when the rest of Asia, in particular China, started catching up with its own run of economic growth. But Taiwan has since successfully transformed itself in the face of the heightened competition.

Gone are the labour intensive factories. In their place have come high-tech wafer fabrication plants, making Taiwan one of the world’s leading semiconductor manufacturers.

“Taiwan is one of the higher rated countries in Asia. Its economy is strong, quite open and also relatively competitive,” said Steffen Dyck, senior analyst in the sovereign risk group at Moody’s. “While it lacks the global brands that countries like South Korea possess, it has a very specialised manufacturing industry that caters specifically to technology giants such as Apple, which has so far proven to be very successful.”

The country’s economy grew around 3.7% in 2014 and is expected to hit more or less the same figure in 2015, according to Taiwan’s statistical bureau. That is a far cry from the 1990s, when it grew on average 6%-8% per year, but Dyck said it is still impressive given that Taiwan's GDP per capita is one of the highest in Asia — and even trumps several developed countries in Europe. Taiwan’s 2014 GDP per capita was $22,631 and is expected to reach $22,823 in 2015.

Political headwinds

Most importantly, those numbers were achieved despite considerable headwinds from China, with which Taiwan enjoys an improved, but still uneasy, relationship. While similar export-driven economies such as Singapore and Hong Kong have benefited immensely from China’s rise to power, Taiwan has been unable to do so fully.

One example of the challenges faced is the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), an agreement signed in 2013, which will open up Chinese and Taiwanese service industries such as banking, healthcare, tourism and telecommunications to investments from both sides.

However, the CSSTA has yet to be ratified by the Taiwanese legislature and attempts to push it through in 2014 led to large scale student-led demonstrations known as the Sunflower Student Movement.

“The demonstrations were triggered by how the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party tried to force the issue without fully consulting with the legislature,” said a Taiwan based syndicated loans banker. “But the underlying cause is still the fear that China will be able to exert control on Taiwan economically, and also how domestic business will be forced out of the reckoning in the face of competition from across the Strait.”

But the banker pointed out that shunning China will only do more harm than good because the domestic market is in need of fresh impetus.

“Taiwan’s domestic market is too small and China is too big to ignore,” the loans banker said. “In Taiwan, all the infrastructure has already been built and the economy is fully developed. There’s little room to grow domestically, so the only way left is to go overseas or attract foreign investment.”

Too many cooks

With an average annual return on assets of 0.42% over the past 10 years, Taiwan's banks, for example, are one industry that has been struggling in a limited domestic market. The low returns are a result of too many banks fighting over too few names to fill their loan books.

Many have now turned their attention overseas in a bid to overcome a scarcity of opportunities at home. Offshore lending, of which most is to Chinese companies, has grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21% since 2010. By comparison, domestic lending only grew at a CAGR of 4% over the same period of time.

That kind of growth makes regulators jumpy. Fearing overexposure to China, the Taiwanese authorities have imposed a cap on how much Taiwanese banks can lend to Chinese corporates. That cap is set at the net worth of the lender and most have already reached the limit.

“The rules are created with good intentions in mind, because having too much exposure to a single country is never a good thing," said the loans banker. "If something goes wrong in that particular country then you’re bust. We understand that, but it doesn’t change the fact it has severely restricted us from lending to the most capital hungry country in the world.”

Another Taiwan based debt origination banker agreed that the cap has not been helpful. While he would like the cap removed or at least increased to 200% of net assets, he conceded that such a move was unlikely to happen considering the increased political sensitivity towards China since the 2014 protests.

“Increasing the limit now when everyone is talking about overexposure to China is political suicide,” the origination banker said. “The authorities will never make that move, especially with presidential elections coming up [in 2016].”

As a result, Taiwanese banks have had to turn their attention still further overseas. Many are now improving their portfolio mix by lending to southeast Asia, a move that neatly follows the migration of manufacturing bases from China to the likes of Cambodia and Vietnam.

While the ASEAN region could well become an important source of income, expensive acquisitions of local franchises will have to be made in order to get a proper footprint in the region, something that smaller Taiwanese lenders will have trouble doing. One way to tackle this, according to the debt origination banker, would be to consolidate Taiwan's banks into bigger entities. These would naturally be in a much stronger financial position, which would allow them to expand overseas much easily.

It could also solve the problem of a crowded sector at home, and that should mean better margins. “If the pie isn’t getting bigger, then we should aim for bigger slices,” the banker said.

Taiwan’s Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) has made tentative steps over the past year to set the stage for consolidation. It has already selected state banks such as Mega International Commercial Bank and First Bank as potential acquirers, but labour issues have meant that progress is slow.

ECM sluggish

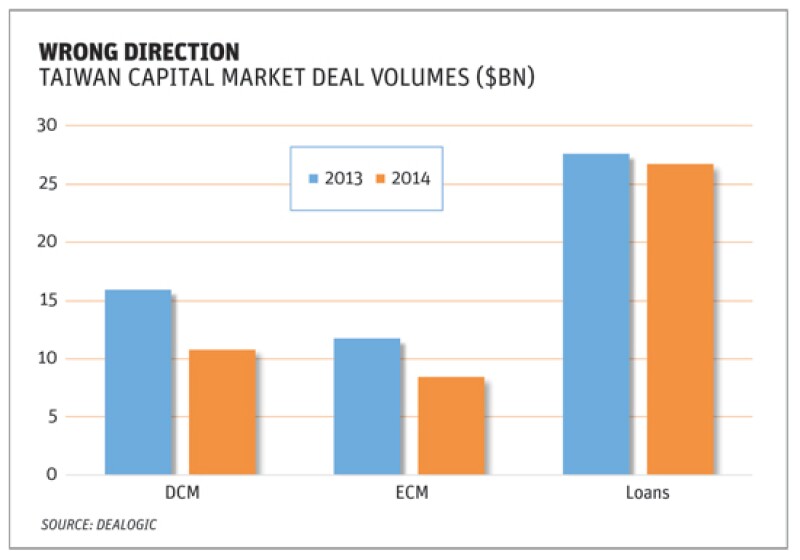

With the loans market stuck in the doldrums, things are not looking any better in the equity capital markets. Volumes are declining, thanks, once again, to a limited domestic market. ECM volumes were just $8.4bn in 2014, a 28.2% drop from 2013, according to Dealogic. And there were only seven IPOs amounting to a paltry $237m.

“ECM activity is triggered by mostly either acquisitions or restructurings,” says a Hong Kong based head of ECM of a bulge bracket firm. “But neither of those is happening in Taiwan because the market is already saturated.” He points out that most of the big companies were already publicly traded and the ones that have not listed are too small to do so — and are unlikely to be able to grow much.

With the pool of domestic companies capable of listing shrinking by the day, the next best option would be to try and attract foreign companies to Taiwan's bourses.

But the likeliest candidates would be mostly from China, and the bigger names would prefer Hong Kong or the US, where companies enjoy much deeper markets and more publicity. Tech giant Alibaba, for example, landed on the New York Stock Exchange for a record-breaking $25bn last year.

In any case, for now Chinese names are largely prohibited from listing in Taiwan, although Alex Chiang, a Taipei based senior consultant for law firm Baker & McKenzie, notes that an amendment to listing rules in 2008 allows Chinese companies that are majority controlled by Taiwanese entities to float on the Taiwan Stock Exchange or the GreTai Securities Market.

“It’s a hot topic in Taiwan right now and good because it’s helping to increase the market cap of the stock exchanges in Taiwan, and creating new exit avenues for the vast amount of floating money in the market,” Chiang said. “It won’t be a major trend but definitely helpful nonetheless.”

An over-reliance on Chinese exposure is something Taiwan has been actively trying to balance. On the equity market side, this has included collaboration with other countries. It recently signed a cross-trading link with the Singapore Exchange, which allows investors to trade stocks on both bourses, starting on July 2015 — in a similar way to the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect. The exchange is also in talks with the Tokyo Stock Exchange to have investors in both countries freely trade exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

“We’ve seen first-hand [through the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect] how valuable such trading links could have in terms of boosting liquidity in a stock market, so I’m hopeful all these agreements could have a similar impact on the Taiwanese market,” says one Taiwanese ECM banker.

Hong Kong’s benchmark Hang Seng index, for example, has gone up by more than 17% since the start of the year to close at 27,653 on April 17, close to a seven year high. The stock market’s buoyant performance was the result of a surge of liquidity from China, with southbound volume, or investor traffic from China buying into Hong Kong stocks, reaching HK$8.13bn ($1.05bn) on April 17 alone.

But in the eyes of the ECM banker, simply boosting liquidity in the Taiwan market is not good enough. He thinks that what Taiwan needs to do is to change the composition of its equity investor base, which currently consists mostly of retail accounts.

The trading links, however, do not rectify this problem — and in fact could serve to make it worse, since retail investors are the ones that are restricted from buying stocks on overseas exchanges. Institutional investors already have access to most markets, so the trading links are unlikely to have an impact on them.

Going international

Unlike in loans and ECM, market observers are a lot more optimistic about the prospects of the country’s debt capital markets even though volumes declined in 2014. The $10.8bn raised was a decline of more than 30% from 2013.

The figures do hide some positive trends, however. Taiwanese issuers have been much less active, but so far in 2015 this has been compensated for by an influx of international credits issuing Formosa bonds, renminbi-denominated bonds listed on the GreTai. Formosa bond volumes have already passed Rmb13.35bn since the beginning of 2015, more than six times the volume seen in the same period last year.

Two reasons are driving this. First is a favourable CNH-USD cross currency swap, which allows issuers to enjoy lower borrowing costs when swapping the proceeds back to dollars. International names such as Goldman Sachs and Export-Import Bank of Korea (Kexim) are just some of the borrowers to have tapped the Formosa market this year, with most issuers being able to shave 5bp-10bp off their borrowing cost compared to printing in dollars.

Second is the activity of Taiwanese insurance companies, which have become the main source of buyers of Formosa bonds. Before June 2014, these cash-rich investors were limited in their ability to buy Formosas because of a 45% foreign investment limit. But a regulatory change that now defines Formosa bonds as domestic investments has released them from that cap, opening deals up to a much deeper investor base.

At about Rmb320bn, Taiwan's offshore renminbi deposit base is the second largest in the world (after Hong Kong). But a lack of investable products in the past means that most of it is sitting in banks earning perhaps 1%-2%. Formosa bonds, on the other hand, can yield around 5%.

“If you look at the entire capital market development of Taiwan, this [Formosa bonds] is by far the most successful because we are able to benefit from China [in the form of RMB investment] without adding to the risk of overexposure,” says a business development manager at the GreTai.

“By tweaking the rules slightly, we were able to take advantage of the country’s huge RMB deposits and give both the buy and sellside what they want.”