There was an era, not so very long so, when deregulation was de rigueur in banking. Regulators strove to break down walls harder and faster than their peers, with some seeking to be as invisible as possible, while foreign investment, notably in markets emerging from the grip of communism, was actively sought and put to good work.

Across central and eastern Europe, huge swathes of countries’ banking sector came under the control of mostly western European lenders, from Italy, Austria, Germany and the Benelux countries. In June 2018, Raiffeisen Bank noted that while the overall market share of foreign lenders was inching lower, after peaking in 2006, they still exerted an unusually high level of control across the CEE region.

At the end of 2017, according to data from the Vienna-based lender, foreign institutions collectively owned over 80% of the banking sectors of Albania, Romania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Czech Republic, while in Slovakia, the share is close to 100%. But most of the deals that saw Western lenders crowd into the region were completed long ago. It has been years — a decade, perhaps longer — since a banking sector in emerging Europe or Central Asia flung open its doors to foreign investors.

But very quietly, a question is being asked: will Uzbekistan be next? It is not such an outlandish idea. Until Islam Karimov, a dictator who jailed opponents and brooked no dissent, passed away in 2016, the country’s financial sector was all but off limits to outsiders. Few expected his successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, to be any different: after all, he was after all part of Karimov’s inner circle, having been prime minister since 2003.

New broom

Yet the new president surprised everyone by reaching out to financial investors, foreign lenders, and multilaterals. The EBRD was invited back in after a decade’s absence and quickly got to work, extending credit to local banks in order to spur private sector credit growth. Funding also flowed in from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank and its private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

In September 2017, Mirziyoyev lifted exchange restrictions on the Uzbek som, devaluing the currency by 90%. At a stroke, that eliminated a key obstacle to foreign investment, and brought the official rate in line with the prevailing rate on the black market. Capital controls were eased, albeit partially, and in February 2019, the country celebrated a much-coveted double-first, by securing its inaugural sovereign credit rating, and printing $1bn worth of Eurobonds, which it marketed and sold, with considerable success and no little fanfare, to international investors.

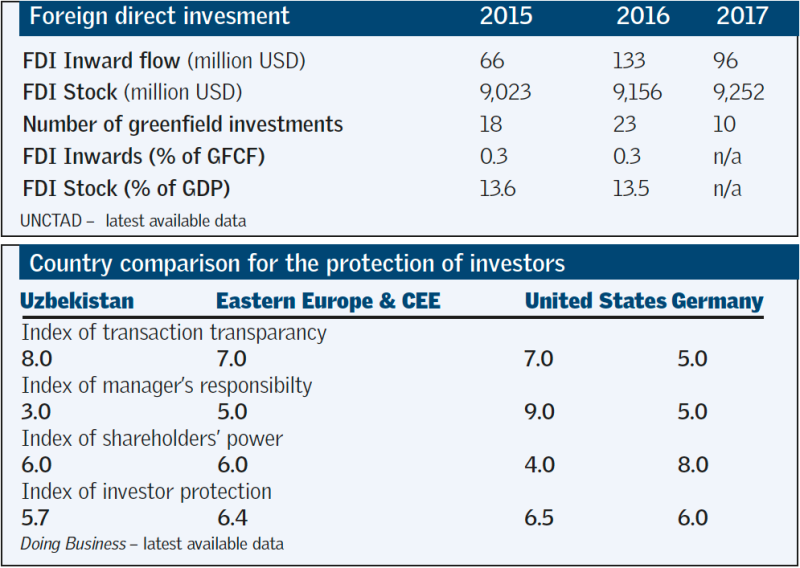

Foreign direct investment started to flow in. That process has been hesitant: some of the world’s most valued corporate brands, accustomed to posting profits in the toughest conditions and markets, have been badly burned in the past. But it seems inevitable that Uzbekistan will strike an abundance of deals in the years ahead, enabling foreign mining and energy giants from London, Melbourne, Beijing and Rio de Janeiro, to tap into its vast reserves of energy and minerals. If Uzbekistan gets it right, the partnerships it strikes will benefit everyone.

The banking sector looks set to open up too. True, the government is still “heavily involved in the economy, especially in banking”, Moody’s said in a credit opinion on the sovereign, published in February 2018. State-run banks are overwhelmingly predisposed to channelling valuable capital to state-run firms, as is the case not just in Central Asia, but in other big economies like Russia, China and India.

Meanwhile, the few local private sector lenders that do exist, while ambitious, are hamstrung by a paucity of capital and funding. Hamkorbank, the largest of its kind in Uzbekistan, a well-run outfit that focuses on SMEs and micro-lending, posted total assets of just UZS5.43bn ($640,000) at the end of 2017, its financial records show.

But there is little doubt that the sector is, slowly but surely, opening its doors to foreign investors. The ADB owns an 11.05% stake in Ipak Yuli Bank, a joint-stock commercial lender founded in 1990 that employs 1,700 staff across 16 branches. In November 2018, Ipoteka Bank asked the IFC to plan and oversee a complete overhaul of its operations and strategy. And in November 2018, Zurich-based impact investor responsAbility bought half of the IFC’s 15.4% stake in Hamkorbank.

TBC Bank, Georgia’s largest commercial lender, has also entered the fray, securing a licence to operate a mobile banking service called Space, with the aim of becoming an onshore leader in the digital space. Next up, TBC aims to open physical branches in the country’s leading cities. And in 2018, Sturgeon Capital, a London-based investment manager that specialises in buying assets in frontier markets along the New Silk Road, bought a 39.6% stake in Universal Sug’urta, an insurer that owns a little under 10% of Universal Bank, a local joint-stock lender founded in 2001.

“If you look at the overall data, it is still astonishing how little exposure foreign banks have to the country — around $4bn in total funding and loans,” says Gunter Deuber, head of economics, fixed income and foreign exchange research at Raiffeisen Bank. “It’s next to nothing. But it has changed and it continues to change. The overall exposure is increasing. This used to be an isolated market, but across the banking sector, the feeling is that Uzbekistan is really starting to open up.”