Since South Korea issued the first sovereign Panda bond — bonds from foreign issuers sold onshore in China — in 2015, plenty of borrowers have followed.

The Canadian province of British Columbia issued two Pandas totalling Rmb4bn ($600m) in 2016 and 2017. Hungary visited the market twice in 2017, raising Rmb3bn. Poland and the Emirate of Sharjah brought deals last year.

Now, Italy is said to be looking to price its own Panda debut as it courts the Belt and Road Initiative — China’s international trade and infrastructure development programme.

But other than raising a pot of renminbi for the borrower, what do these deals achieve?

In many cases, sovereign and sub or quasi-sovereign Pandas look like souvenirs following high-level state visits.

One example is the lesser spotted Panama Panda. The deal was announced in November 2017, after Panama’s president, Juan Carlos Varela, met with Chen Siqing, chairman of Bank of China. Four months later, Dulcidio De La Guardia, the finance minister, said that a $500m Panda would be launched by the end of 2018.

But so far the Panama Panda has proved appropriately elusive, the deal suspended because of diplomatic hurdles, GlobalCapital understands.

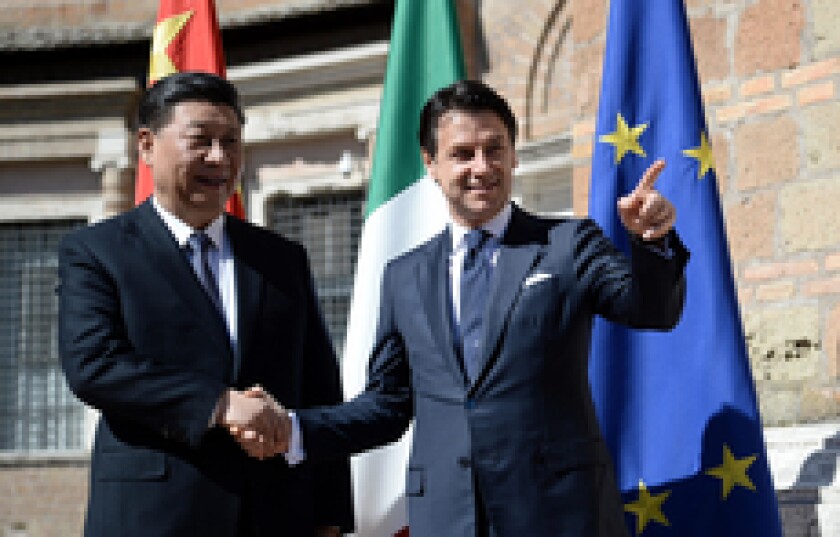

Panama is not the only issuer to have volunteered a deadline for issuing a Panda bond. Italy on March 20, following the state visit of Chinese president Xi Jinping, promised its state investment bank Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP) would issue a Rmb5bn ($745m) Panda “in the coming weeks”.

“Good luck with that,” was the response from one onshore debt capital markets banker on hearing the news.

Sovereign Pandas are not the sort of deals that do what government bonds do in many other markets: set a benchmark to attract more issuance from that country’s corporate issuers.

Sovereigns care more about their relationship with China than the timing of a deal it seems. But corporate borrowers looking for a benchmark need reliability of execution. When bilateral relationships with China cool, it appears Pandas hibernate. Corporates need a sovereign that is out in all weathers.

But even those sovereign Panda deals that do make it do not seem to open the door for corporates from the issuing country. Or if they do, the corporates do not seem to pass through it.

None of the five sovereign, quasi or sub-sovereign Panda issuers has attracted compatriot companies to follow their paw prints.

Conversely, issuers such as Air Liquide of France, Rusal of Russia and Germany’s Daimler have not needed to track a sovereign deal to price their own.

Bamboo-zling bonds

The sovereign bonds that have come have not succeeded in educating Chinese investors about their countries or the way international credit rating works either.

For example, Baa3/BBB/BBB rated Hungary priced its most recent Rmb2bn three year Panda at 4.3% in December. But A3/BBB+/- rated Emirate of Sharjah had to sell a Panda of the same size and tenor at 5.8% back in February 2018, simply because the emirate is not as well-known a name among Chinese investors. Both are rated AAA by domestic credit rating agencies.

A source at one of those agencies admitted that some Belt and Road countries pondering a Panda print do not have “pretty enough” international ratings. The domestic ratings, always above AA, are there to comfort onshore investors.

A boost for foreign corporate issuers would be for their governments to nurture good relationships with the Chinese Ministry of Finance, it has been said.

Another sticking point for corporates, that sovereigns do not have to endure, is the requirement to match Chinese accounting standards. This has proved a tricky negotiation with China’s Ministry of Finance for international issuers.

The Panda market has not flourished as a source of capital for most corporate issuers even though many are likely to have a growing need for Rmb in the coming years as China opens up its economy.

If China wants its Panda bond market to blossom into a genuine global funding alternative it must find ways to boost its fertility for borrowers. This means making market access easier for corporates among other things, but also it means ensuring that sovereign Panda bonds become reliable benchmarks.

Or to put it another way, that they offer more than something that might look appealing but that would have died out were it not for governments whose primary purpose was making friends with each other.