When a group of leaders collectively seem incapable of organising a bunch of ducks to come flocking for bread — let alone getting them in a row — the respect they may once have commanded starts to crumble away.

How could Andrea Orcel, Ana Botín and Axel Weber have let it come to this?

The famed FIG dealmaker, admired chairman of Santander and über-steady former Bundesbank president have, respectively, lost a dream job, her personal pick for CEO, and the head of UBS’s investment bank — as well as, potentially, one of the bank’s best clients.

Should Orcel have known Santander could not realistically pay him €50m to compensate him for losing his restricted UBS stock, when he accepted Botín’s job offer? Did Botín miscalculate in thinking Weber would let Orcel keep some of the stock, since he was going to a top client? Should Orcel have moved more slowly, or sacrificed some millions to secure his next A-list job — and preserve his reputation as a deal Midas?

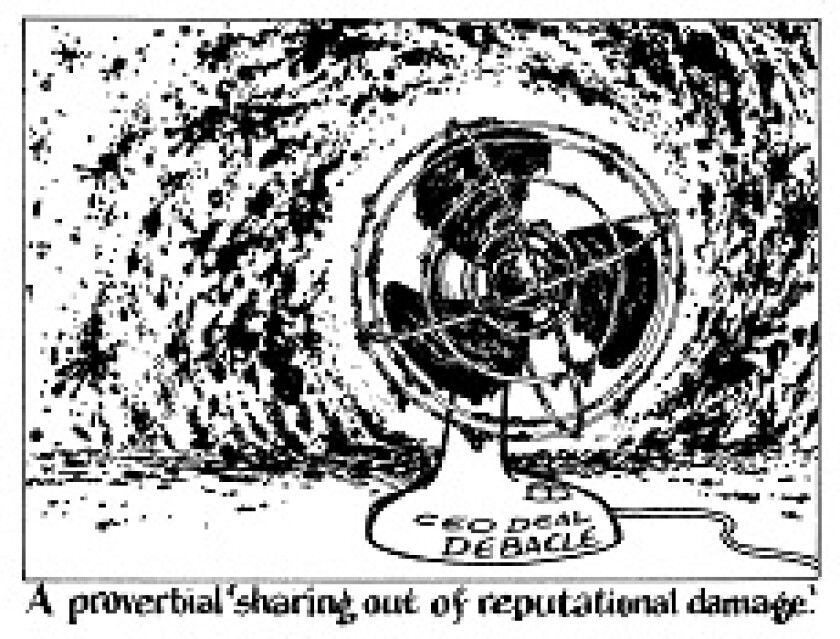

Observers will share out the reputational damage differently, but damage there certainly is.

The system also deserves a knock. Restricted stock awards make sense as a way to claw back rewards from bankers whose deals go sour later. Non-compete clauses that bar bankers receiving this delayed pay, just because they move to a competitor, serve no one. The right staff need to be able to move to the right jobs. People who are chained to their jobs are unlikely to be the best at motivating others.