One could be forgiven for being unimpressed with Japan’s green bond market, given the size of the country’s bond markets in general, and its retail investors’ pioneering efforts as the first regular buyers of socially responsible investment (SRI) bonds.

Not only have just a handful of Japanese issuers sold SRI bonds in the international capital markets, tapping European and US institutional investors for funding, but domestic issuance has been sluggish outside of the retail-focused Uridashi market.

But now interest in the country’s SRI bonds is growing among both its borrowers and investors.

Development Bank of Japan (DBJ) was the first Japanese issuer to sell a green bond in the euro market in 2014, with a €250m bond that financed green real estate assets.

Following that debut, as DBJ sought to expand its SRI financing programme, it created a sustainability bond in 2015 to finance its Environmentally Rated Loan Programme, lending mainly to Japanese manufacturers, which the agency started in 2004.

Ryohei Matsumoto, assistant director in the treasury department at DBJ, says green and sustainability bonds are a way of attracting a broader range of investors, both domestic and international, to the issuer’s bond programme.

“We have only recently started issuing non-government guaranteed bonds, so we need a ‘hook’ to appeal to investors,” he says. “The plan has been successful. In the latest sustainability bond transaction, we issued our first benchmark non-government guaranteed international bonds and the demand was over threefold.”

Matsumoto makes it clear that opening new lines with overseas investors is a key aim for DBJ’s green bond programme, given the scarcity of Japanese versions of the product in international markets.

“We are committed to continuous issuance in international markets, which is still relatively rare, and I hope this makes our bonds attractive to international investors,” he says.

But the agency also wants to tap into growing domestic demand, and it is not the only issuer looking to do so as Japanese institutional investors bring more muscle to the SRI bond market.

Life insurance companies in particular are understood to be committing larger portions of their investment portfolio to green and SRI bonds. Matsumoto says that some of those institutions have been involved in green private placement transactions, while some are understood to have been involved in international deals in recent years.

Masanori Kazama, vice-president in debt capital markets at Nomura says the drive is coming from increasing numbers in Japanese insurance companies looking to demonstrate their environmental, social and governance (ESG) credentials to investors in a landscape featuring few dedicated green bond funds.

While DBJ targeted European investors with its initial SRI prints, attracting Scandinavian pension funds and corporate treasuries, for its second sustainability bond in 2016, DBJ switched currencies from euros to dollars, to attract more Japanese investors.

“Issuing in dollars is more friendly to Japanese buyers,” says Matsumoto. “They are increasingly aware of the importance of SRI investment, but their budget for investment in euros is more limited.”

Local bonds for local people

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government also wants to tie its new municipal green bond programme to the domestic investor base.

Last year it said it would establish a Tokyo Green Bond programme to support the financing of environmental projects in the city. The programme would be the first municipal green bond programme in the country.

Speaking at the launch of the programme in October 2016, city governor Yuriko Koike pointed out the involvement of Japanese life insurance companies in green bonds issued in international capital markets, and said she wanted to make use of this money to target environmental measures at home.

There are a host of environmental projects to finance as the city prepares to host the 2020 Olympic Games, including smart energy development, improvements to public parks, sewerage pipes and storm-surge defences.

It plans to issue ¥20bn of Tokyo Green Bonds in the 2017 fiscal year. The city will sell these to both institutional investors in yen, and to retail investors in various currencies — but only Tokyo residents will be eligible to buy the retail-focused bonds.

Eiki Ohashi, deputy director in the foreign bond team of Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG), says the local government is not aiming to target overseas institutional buyers with the bonds in the coming fiscal year, but says that if they have the capability to buy yen products, “they can buy it”.

More Japanese investors are considering green investments, he says. “Many investors are expected — or need — to consider green investment because of growing environmental consciousness,” he says, as a result of the Paris climate change agreement, which was ratified in October 2016.

The TMG’s issuance policy talks of the importance of creating a flow between domestic funds and local environmental projects, and “awakening a sense of ownership among Toyko residents” of environmental projects by offering them investment opportunities in the schemes.

In 2016, Tokyo floated a test balloon in the form of Tokyo Environmental Supporter Bonds, which complied with the Green Bond Principles — the International Capital Markets Association’s (ICMA) framework for green issuance — but did not obtain third party verification. The local government raised A$125m, selling the bonds to retail investors.

Ohashi says that the government has not yet decided which banks will be hired to structure the new transactions, but as they will be issued in yen and are expected to be sold predominantly to Japanese institutions, it is “highly probable” that Japanese banks will lead the programme.

Potential catalyst

Through the Tokyo Green Bond programme, according to a plan released by the government in early February this year, the city hopes to invigorate the green bond market and encourage other issuers to launch similar programmes, creating a flow between domestic funds and local environmental measures across the country.

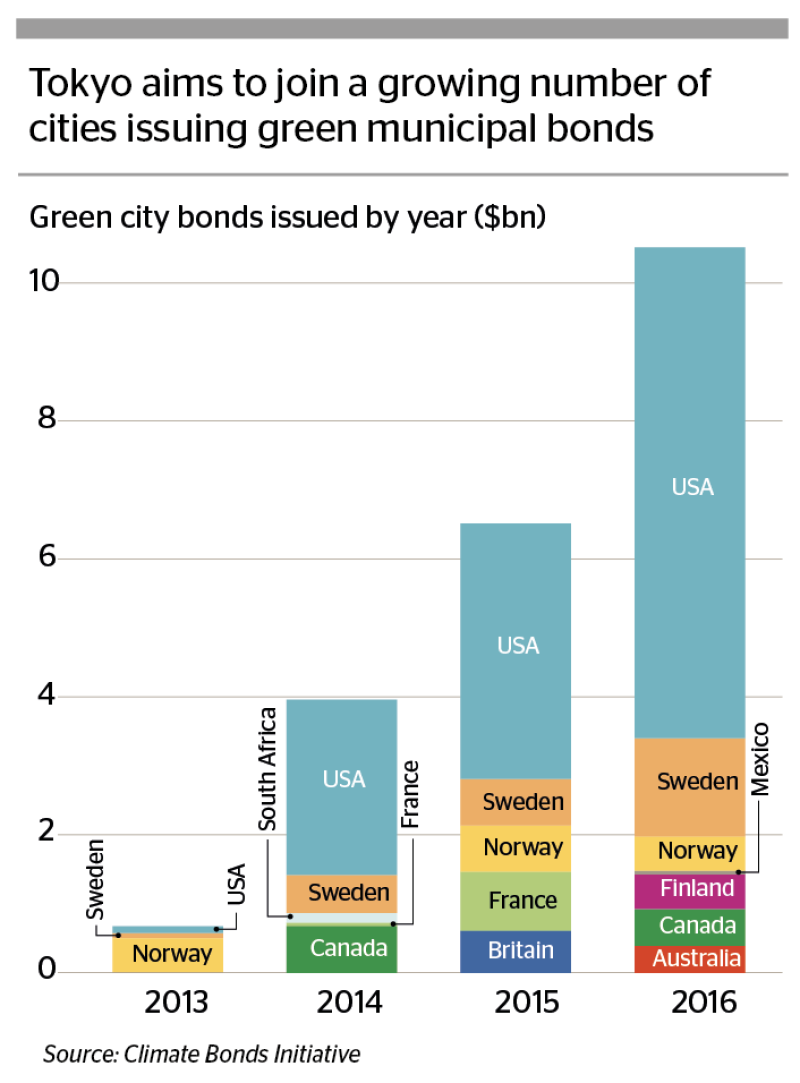

The programme could “kick-start” the country’s green bond market, according to Sean Kidney, chief executive of the Climate Bonds Initiative, who forecasts a breakout year for Japanese bonds in 2018.

“The scale of the Japanese green bond market is quite small, considering the size of the overall domestic bond market, so compared to some others we think Japan is quite late to the party. However, when the market does move, it will move at scale,” he says.

“We expect to see large slabs of green issuance coming. 2018 could be a huge year of growth for Japanese green bonds, in the way that 2016 was a year of strong growth in China.”

The size of the domestic market, however, might be limited by the availability of projects to finance in what is a geographically small and already environmentally friendly country.

“Individual projects might only be small size because Japan, and its manufacturing industry, has already achieved high levels of progress in reducing carbon emissions, so there is only narrow room for further reductions,” says Matsumoto. “As a small country it’s also difficult to construct large scale solar or wind turbine projects. Potential issuers often don’t have the volume of assets they would need to issue a benchmark deal.”

Kidney says that while solar and wind power assets are often the first and easiest assets to finance with green bonds, his organisation sees the most potential in the Japanese property market as a source of green investment projects.

“We’ve been trying to promote a focus on building emissions in Tokyo because robust performance data is available,” he says. “Japanese office buildings are relatively efficient compared to most markets but they’re still not efficient enough, considering the technology and solutions the country has.”

Other obstacles for issuers to enter the green bond market remain high however, according to Kazama, in terms of the cost and complexity of bringing a deal to the market — specifically the need for third party verification of the borrower’s green claims.

“It’s not just the extra work to justify the green credentials of the bond but a language barrier exists, in that most of the second opinion providers are not Japanese which is certainly an obstacle for many domestic issuers,” he says.

Efforts are underway to make this hurdle easier for Japanese issuers to overcome. The country’s environment ministry is working on plans to produce its own set of green bond principles, which are understood to be close to ICMA’s.

Having a set of principals in Japanese would improve the architecture of the market, says Kidney, although the lack of guidelines isn’t preventing the market from developing.

“For bigger issuers and investors, clear definitions of the principles aren’t a huge challenge to overcome but to grow the market to a wider range of participants, definitions are useful,” he says.

Some issuers, such as DBJ, seem concerned about the evolution of green bond principles and whether making the definitions tighter might strangle the development of the market.

“The guidelines seem to grow stricter each year and my concern is that such developments will make potential issuers hesitant to issue new bonds,” says Matsumoto. “That might kill the market.”