Any illusion of calm was shattered just days into 2016 when China, just like it did in the summer of 2015, became the epicentre of another global rout in financial markets. On trading floors around the world, market participants looked on in horror as stocks dove headlong into a downward spiral.

If the turmoil of 2015 was caused by China’s devaluation of the renminbi, then in January it was the disastrous introduction of a circuit breaker that sent markets into a tailspin.

The instrument halted trading on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges twice just four trading days into 2016 before being scrapped. But that would not be the last time markets went into panic mode this year, as global macro events such as the UK’s decision to leave the European Union, or Brexit, and Trump’s win triggered similar instances of terror.

“January was a period that we would not only like to forget, but remove from history altogether,” said a senior equity capital markets banker at a US firm.

“We had to reset expectations for 2016 right off the bat. But even after January, there were a handful of surprises that the market was either not set up for or had responded to in the extreme. All those events put investors on the defensive, and we had to dig ourselves out of that hole and get their confidence back.”

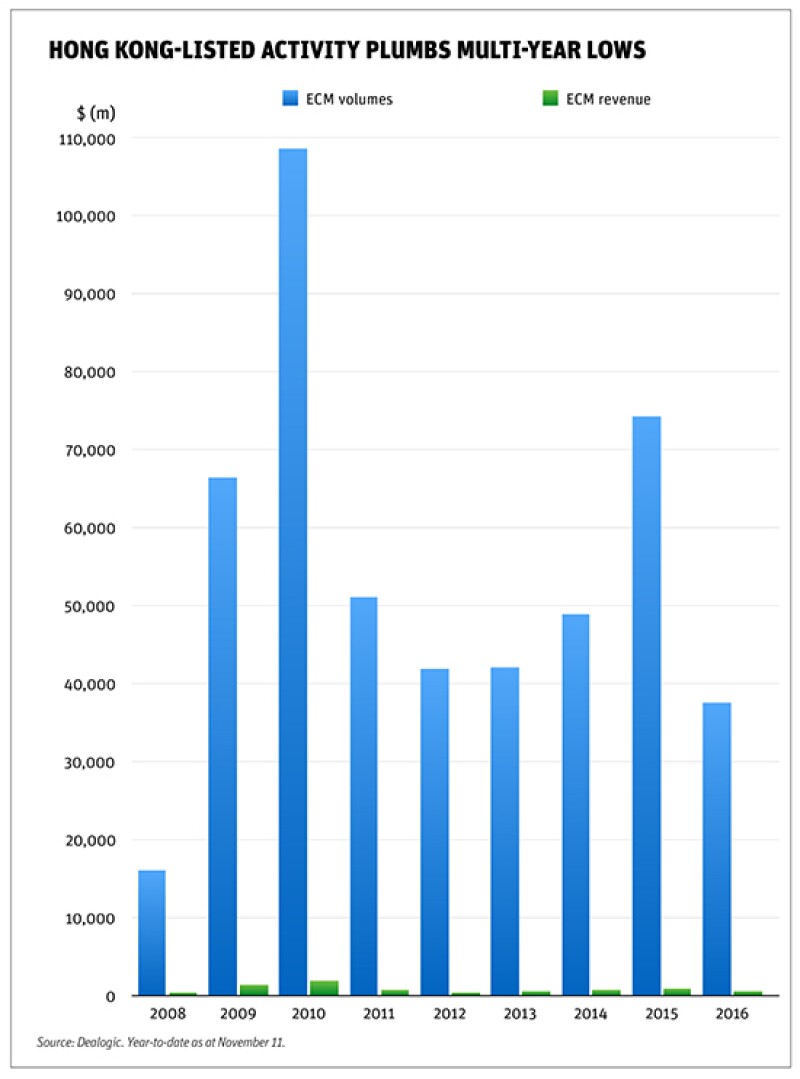

Those early months saw ECM bankers couching their head in their hands. Some feared the worst as investors complained of ever-dwindling returns, banking jobs were cut and share sales were pulled. Many of the deals that made it across the line in the first half did so only with extraordinary support from Chinese investors. “We had thought that after 2015, this year would be quiet, but we didn’t expect it to be this quiet, especially in the first half,” said Citic CLSA Securities’ head of Greater China corporate finance and capital markets Wang Changhong.

“Despite China’s expected growth of more than 6%, investors were concerned about the quality of growth and whether it was too reliant on government stimulus. On top of that, rising bad debt ratios in the banking sector and the drop in private sector investment made investors hesitant.”

All in the family

That hesitance among global funds led to cornerstone investors, especially Mainland corporates, soaking up a record amount of stock in Hong Kong IPOs. As at November 11, they had bought 55% of all share debuts in the city versus 41% for all of 2015, according to Dealogic.

This prompted a head of ECM at a bulge bracket in Hong Kong to call 2016 the year of friends and family. “It had to be this way due to valuation issues,” he said, referring to China’s ban on sales of state-owned assets for less than book value.

Ada Wat, a member of UBS’s ECM syndicate in Hong Kong, said that banks have had to double down on efforts to de-risk trades. In addition to courting investors during bookbuilding, this year syndicate desks have put just as much emphasis on the pre-launch stages of an IPO securing orders from cornerstone and anchor accounts, Wat said.

The cautious sentiment that prevailed for much of the year made it essential for deals to launch with a covered book. And nowhere was Mainland investors’ strength in numbers more evident than in the behemoth HK$57.6bn ($7.4bn) Hong Kong IPO of Postal Savings Bank of China, the largest listing globally since Alibaba Group raised $25bn in 2014.

Postal Savings Bank tucked away some 76% of its shares with cornerstone investors, mostly Chinese state-owned firms, allowing it to rank second only to China Development Bank Financial Leasing Co in terms of Hong Kong listings of above $500m with the highest cornerstone tranche.

“Cornerstone investors provide certainty in a tough environment,” said Citic CLSA’s Wang. “But it’s important to pick the right investors. If they can establish a strategic relationship with the issuer and are willing to be locked up for six months to show long-term commitment, then this sends a message of confidence to other investors.”

The turmoil at the beginning of the year led to share sales being shelved for the second and third quarters. Despite their waiting, issuers still had to navigate fundraising windows that snapped shut whenever investors decided to capitulate.

Just as calm was starting to return, markets were again jolted by Trump’s triumph in the US presidential elections on November 8. Market watchers say there is no way to predict what comes next, although several things became certain in the weeks following the vote: US monetary tightening, a stronger dollar and weaker emerging market currencies.

The surge in the dollar at the end of November prompted outflows from Asia, forcing central banks to defend their currencies as the rupee, rupiah, ringgit and peso all took a beating.

Yet for all of Trump’s anti-China rhetoric, market observers do not believe he will act to the detriment of US-China relations. Issuers, at least, seemed not to care – deals in Asia started printing the day after the election result.

Rays of hope

Bankers too expressed hope that ECM would return to form. In the H-share IPO pipeline for 2017 are offerings from the FIG space and healthcare, but the most anticipated of them will be fintech.

“After some large deals priced this year, we’re expecting momentum to pick up,” said UBS’s Wat. “This is a cyclical industry and we are past the trough. It remains to be seen if the path will be smooth, but the worst is behind us.”

“We have a healthy pipeline of high quality issuers going into 2017 for a number of large IPOs. To some degree, things seem to have turned a corner and we could see volumes begin to normalise next year,” said Jason Cox, co-head of Asia Pacific ECM at Deutsche Bank.

Kefei Li, who is co-head with Cox, said FIG would continue to drive volumes in 2017, as selected Chinese banks, insurers, asset management companies and leasing companies head down the IPO route.

“FIG was a big theme this year because a lot of Mainland brokerages were racing to build up their capital bases and expand overseas, giving them the impetus to list in Hong Kong,” said Li.

With better stability coming through in the fourth quarter, Citi’s co-head of Greater China ECM and vice chairman of Japan capital markets origination, Bruce Wu, said there could be more execution-friendly windows for issuers and less acute price sensitivity from investors.

“When investors are less preoccupied by macro-driven market movements, they have more bandwidth to focus on company and industry fundamentals,” he said.

Credit Suisse’s head of ECM for Asia Pacific Johnson Chui also points to the tailwinds lifting the market into the year-end and 2017. “We expect to see new concept plays and other traditional sector companies tapping into disruptive technologies next year, such as in the fintech space,” he said. “Investors are seeking out deals and have the risk appetite for them. The issue this year has not so much been a lack of demand, but a lack of supply.”

Even as names like Ant Financial, Lufax and Zhong An Online P&C Insurance are expected to add plenty of excitement to the market next year, questions are being asked about whether the regulatory landscape is ready to receive them.

Market watchers say there have been serious discussions on how Hong Kong can continue to be attractive for listings. Many believe the regime is in need of a shake-up if the city’s exchange wants to be relevant to technology issuers.

“There’s a disconnect between what the regulations allow and natural business cycles,” said, Allan Yee, a partner at law firm Norton Rose Fulbright.

“Unlike the US, the Hong Kong main board doesn’t allow smaller sized companies with no profit track record to list, but private equity or venture capital investors have a finite investment horizon and many won’t wait until their investee companies turn a profit before exiting.”

The big picture in China, however, remains one of improving fundamentals. Key to this has been the stability of the renminbi, which has helped draw a line under the A-share panic in January, reckon equity analysts and strategists.

Erwin Sanft, head of China strategy at Macquarie Securities Group, calls 2016 a year of recovery for China, attributing this partly to the government’s infrastructure spending initiatives.

DBS equity strategist Joanne Goh agrees, saying that the renminbi has been one of the biggest surprises this year, defying expectations that it would fall up to 7%. “Pressure on the currency has decreased because of its inclusion in the special drawing right basket,” she added.

Sanft thinks the People’s Bank of China will take the necessary steps to dampen depreciation expectations, with Macquarie forecasting a mild appreciation in the renminbi.

Bottoming out

But even in a year when volumes have plunged more than 40% in Asia ex-Japan ex-onshore China, unconfirmed reports in September that said Goldman Sachs was retrenching up to 30% of its staff in the region still had the ability to surprise.

The exact number of cuts was not disclosed, although people familiar with the matter say the final figure was closer to 15% of its 300-strong investment banking headcount in Asia ex-Japan. The bank declined to comment.

The move follows layoffs earlier in the year by mid-tier firms such as Barclays, CIMB and Nomura, which saw the axe falling mostly on equities divisions. Observers blamed the cuts on slowing revenue growth, competition from Chinese banks and higher operating costs.

That Goldman had contemplated reducing up to a third of its workforce has dramatic implications for global investment banks in Asia, according to a Hong Kong-based headhunter.

“This is the time to ask if you stared long enough at your navel this morning,” he said. “The news sent chills down the spines of many bankers, and it would be naive to think there will be no more cuts elsewhere. Costs and return on equity are still massively out of whack at global banks.”

Some, like Citic CLSA, have sought other ways to reduce costs, with the firm allowing staff to take voluntary unpaid leave of five or ten days to weather the market downturn. But while the competition for fees in Hong Kong looks like a race to the bottom, the second head of ECM said Mainland banks should not shoulder all the blame.

“The international banks are their own worst enemy,” he said. “A decade ago, underwriters on Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s IPO made $60m each. On Postal Savings Bank, a joint global co-ordinator pocketed $15m-$20m, and the junior banks far less. The reality is that investment banking in Asia is no longer a blue sky.”

Postal Savings Bank topped the list of the most number of bookrunners on an IPO globally, with its 26-bank syndicate splitting $118m in fees between them.

At the heart of the issue is also the question of whether IPOs have become a commodity business, and whether global banks still bring value to the table.

“Chinese issuers are seeing less and less value in hiring global banks,” said a corporate lawyer. “State-owned enterprises have an untouchable mentality and only care about obtaining the highest possible valuation from friends and family. They just need a sponsor to tick all the boxes for a Hong Kong listing.”

The first ECM banker disagrees. “It’s true that A-share issuance has made up 70% of Asia ex-Japan volumes, compared to the 30% we’re used to, and that Mainland banks are rising up the global league tables,” he said. “But 12-18 months don’t make a trend.

“To say that China is shutting out global banks or investors would only be true if China intends to fund itself forever. But looking at all the efforts at reform, like giving foreign investors access to the onshore bond market or the Stock Connect, that’s clearly not the case.”

Colin Law, China managing partner at law firm Shearman & Sterling, said that while Mainland lenders have raised the competitive landscape in Hong Kong, this is part and parcel of a maturing market.

“Even though the Chinese banks are more established now, that doesn’t mean global banks don’t have a role to play,” he said.

If nothing else, the international banks can take credit for bringing in Postal Savings Bank’s largest cornerstone investor. And one of the JGCs whose private bank client is Li Ka Shing is understood to have sold structured notes to the Hong Kong billionaire’s charity arm, giving it a 2.8% stake in the state-owned lender.

“China is in extreme headwinds at the moment because of a lack of trust from global investors,” said the first banker. “But the buy-side needs exposure to the world’s second largest economy.”

One thing senior ECM officials can agree on is that things are moving in the right direction.

“Right now it feels like we’ve hit bottom,” the first banker added. “A lot of the uncertainties have been baked in, and the recovery so far is a leading indicator of more a favourable market for issuance in 2017.”