Demand for assets that fall under the socially responsible investing (SRI) umbrella is rocketing. In July, HSBC noted that the more than 1,500 signatories to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment now have more than $63tr of assets under management (AUM). Many of those investors are willing to put their money to work beyond green bonds, so far the most famous SRI asset class. The social bond is one prominent alternative, with a €15.6bn market for the product developing between 2012 and 2016.

Protocols to define and guide the market are still developing, but market participants can already point to encouraging results from those issuers that have sold social bond deals.

State owned Spanish bank Instituto de Crédito Oficial (ICO) issued a €1bn three year social bond in January 2015, directing proceeds into financing SMEs in regions with low GDP per capita relative to the national average. ICO’s end game is to spur employment in those regions.

In a February 2016 report, ICO stated that it has directed the €1bn of bond proceeds to 23,254 small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The bank also attributes around 6,614 new jobs created due to the funding, as well as 154,738 jobs retained. ICO says that the added jobs account for 1.9% of total employment creation in the targeted regions for 2015 and the retained positions for 1.6% of total employment as of the fourth quarter of 2015.

But ICO’s success seems just as, if not more, attributable to it being a social institution than the form of bond it used for funding the project. Its fundamental purpose is, in its own words, to “promote economic activities contributing to growth, the development of the country and improving the distribution of the national wealth”. With a seasoned track record of funding in bond markets, arguably most of its debt’s uses of proceeds are already social.

ICO’s treasury team was aware of this when it weighed up its options for funding the project. The department had noted the rise in green bonds’ popularity but was still wary of issuing a tailored SRI product.

“In the beginning we were reluctant,” says Rodrigo Robledo, head of capital markets at ICO in Madrid. “We are a rated SRI issuer and a lot of our activities are socially responsible so why should we issue something specifically labelled ‘green’ or ‘social’?”

“But the banks were persuasive. They said that it made sense to label our proceeds/activity as ‘social’ or ‘green’ because there are investors with portfolios who can only buy your bond if you construct a package that follows a specific criterion. For us it then made sense to explore the opportunity to diversify our investor base.”

The promise of investor base diversification is set to increase further as demand for SRI assets continues its upward trajectory. The leap forward in green bonds, with global issuance up 79% to $29.9bn in the first half of the year, bodes well for social bonds.

But market participants cannot expect social bonds to rise with the green tide. As with green bonds, developing a clear and transparent product structure will be fundamental to the market’s success. Until then, social bond issuance is unlikely to grow much further.

“We are sustainable investors so will put our money into sustainable bonds and green bonds that are targeted to a dedicated purpose,” says Florian Sommer, head of sustainability research at Union Investments in Frankfurt. “There is no reason why we would not also have social bonds, as long as the use of proceeds are specifically defined for a social purpose. We welcome them on the market but these are very, very early days.”

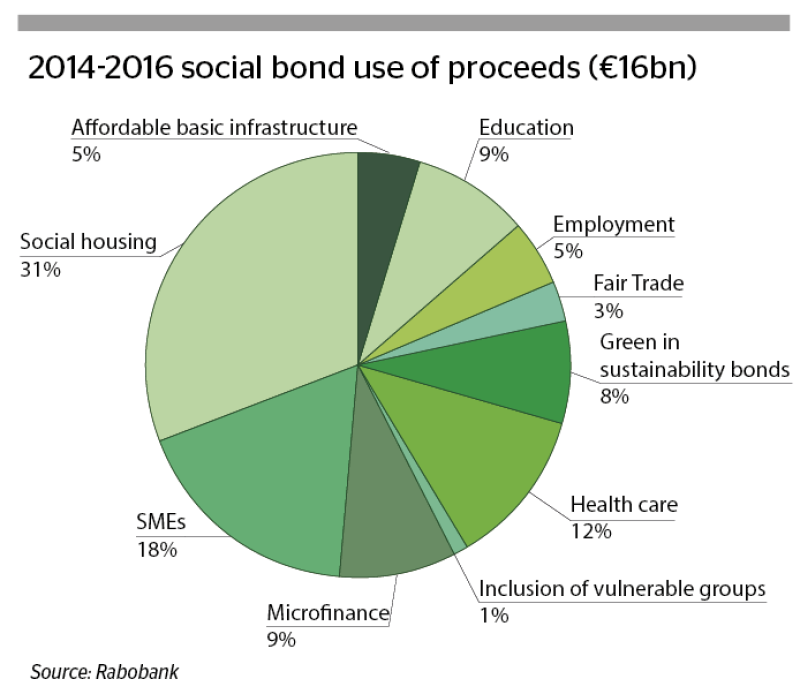

Progress is being made but there are still difficulties, not least in defining the product. Green bonds’ purpose is relatively neatly aligned with reducing carbon emissions and creating environmentally sustainable projects. But social bonds target a much wider and more diffuse array of objectives. Providing access to essential services such as health and education, affordable basic infrastructure and employment generation are social bond project categories as defined by the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA). Market players are also working on potential migrant bonds, which would be issued to address the European refugee crisis.

The broadness of the ‘social’ label has already attracted other products, such as the UK government’s social impact bonds initiative in 2012. Demonstrating the broad reach of the term and the confusion that can create, social impact bonds, a product that based investors’ payments on the performance of public service projects that they invested in, were not even really structured like bonds.

Confused definitions create conflicting interpretations and hold-ups.

“I have been on quite a few roadshows with issuers where they say ‘we have a social or green bond’ and investors will disagree on the definition of social or green,” says Lars Carlsen, head of sales capital markets at DZ Bank in Frankfurt. “You need to have some very clear lines on where the money goes, and a definition that everyone can agree investors will recognise as a green or social bond.”

Recognising this, market participants have been pushing forward recognised social bond guidelines that follow in the footsteps of ICMA’s Green Bond Principles. HSBC, Crédit Agricole and Rabobank last year published a proposal for social bond guidelines that formed the basis of ICMA publishing social bond guidance on June 16, 2016.

As important as establishing guidelines will be aligning them to the green bond market, which ICMA did in an appendix to its Green Bond Principles update. While investors want clarity on what they are buying, they also want a product that fits under the SRI umbrella.

“We welcome the Green Bond Principles being expanded for social bonds,” says Sommer. “Social topics may be harder to quantify and measure than environmental topics, but we still believe that applying green bonds principles to social bonds will be a good fit for sustainable investors like us.”

Tying social bonds to the green bond product in this way aligns the market with a trend in investor demand that will quicken its growth, says Ulrik Ross, global head of public sector and sustainable financing at HSBC in London and one of the authors of the initial social bond guideline proposals.

“We are and will increasingly see investors not just establishing green investment guidelines but a holistic and multi-asset ESG approach to sustainable investment,” says Ross. “That means there will be much more demand for social bonds and it will come from across all portfolios and asset classes. It will not just be a narrow view that dictates the do-good factor for investors.”

Tailoring the product

One increasingly prominent strand of the push to broaden the appeal of assets like social bonds to investors is highlighting their benefits for other objectives of the investor.

These include social bond projects that address socio-economic problems afflicting workers paying into pension funds or those that target health problems, such as diabetes, which strain health insurance companies’ long term liabilities.

That thinking goes beyond a pure focus on portfolio value to an increased awareness about the place institutional investors hold in public discourse and how they are perceived by the public itself.

When Axa Group announced its decision to divest all of its tobacco industry assets in May, the insurance giant cited the changing role of health insurers in society. Preventing and not just curing the non-communicable diseases caused by tobacco was central to this shift, said Axa in its announcement.

“We have seen no difference between asset managers, insurance companies and pension funds in their willingness to invest in social bonds,” says Christopher Flensborg, head of climate and sustainable financial solutions at SEB in Stockholm. “The question is whether you are capable of bringing them to make the investments, so if you can identify the value of the position to the mandate they hold there is a fairly high likelihood that most people will participate. But you need to do the paperwork with the different players.”

While cynics may scoff at the public relations motives of social bond investing, the market’s growth trend is real and investors still need reassurance they will see results before committing to it.

Key to that will be models for demonstrating outcomes to both new and existing investors. Hans Biemans, head of sustainability, markets at Rabobank in Utrecht says that impact reports such as ICO’s will be central to creating that framework.

“There will be a lot more importance placed on impact reporting but it is quite sophisticated and most investors are not yet able to use the model with their investment policies,” says Biemans. “But more mainstream investors will develop these lists [of impact themes they want to invest in], that will mark the next phase of the market.”

For issuers though, the benefits are less clear. Especially for issuers unlike ICO, which do not operate on an explicit social basis. Considering the six to eight weeks extra work required to prepare a social bond instead of a straight bond, the main benefit for using the product still seems to be good marketing.

“For the foreseeable future, social bonds will be driven by much the same considerations as green bonds — there is no clear and consistent funding benefit, but issuers nevertheless see the value of having a platform to present their sustainability practices,” says Stephanie Sfakianos, head of sustainable capital markets at BNP Paribas in London. “But there are potentially some regulatory drivers coming down the track that will enhance issuer’s requirements to disclose non-financial information such as the European Directive for Disclosure of Non-Financial Information and this should provide incentives.”

While increasing supply may take time, when social bonds do come to market, investors will ready and willing to assess the product.

“It is less because pension funds have a new-found fiduciary mandate to make social investments and more because we now actually have products to channel that demand,” says Ross. “Social investment is supply driven, we now have the products that can pre-empt future costs for investors, issuers and society.”