Senior unsecured issuance by European banks is set to fall as strong deposit growth and the European Central Bank’s targeted long term refinancing operation (TLTRO III) limit the need for wholesale market funding. At the same time, it seems likely that loan demand will be anaemic due to the tough economic conditions following Covid-19 lockdowns.

Analysts at Commerzbank expect senior unsecured issuance by banks whose bonds are eligible for inclusion in the iBoxx euro Financials index to fall by €13bn from 2020 to €115bn in 2021. A large part of that sum is expected to be made up of senior non-preferred, which is eligible for meeting the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) rules.

“MREL is the only reason to be in the market,” says Derry Hubbard, global co-head of rates and credit at Danske Bank in Copenhagen. “But with many issuers there is a degree of frustration about taking liquidity when they are so cash-rich and awash with liquidity from high deposit inflows.”

Banks are expected to get a clear definition of their interim MREL requirement from the Single Resolution Board (SRB) by January 2022, at the latest, and the final requirement will be known two years later.

Nordea, for example, has already issued €2.7bn of senior non-preferred and in total expects to issue €10bn by December 2023.

“We’re still working under transitional MREL requirements while awaiting a final decision from the SRB during the first half of 2021,” says Ola Littorin, head of long term funding, treasury and ALM at Nordea Bank in Stockholm.

Nordea did not tap the euro covered bond market in 2020, which is a reflection of its deposit inflows and strong liquidity. But having issued an average of two or three euro deals a year for the previous five years, a reappearance is expected, not least because euro covered bonds offer “an excellent source of duration,” says Littorin.

DNB, which does not have access to the TLTRO and did not change its funding plans in 2020, has a funding requirement of €8bn-€10bn in 2021, of which senior non-preferred will account for 20%-30%.

Its remaining term funding will be mainly in covered bonds, which means it will also be tapping the euro market with one or two benchmarks in addition to Norwegian and Swedish local currency issuance, says Thor Tellefsen, the bank’s head of funding.

No pressure

But even though MREL issuance is compulsory, most banks are not under any pressure. This is particularly the case for German banks which issued plenty of vanilla senior unsecured debt which in the run-up to December 2018 was eligible for MREL. From January 2019 German banks were obliged to issue senior non-preferred but had little need as most had met or exceeded their requirements.

LBBW, for example, is well above its MREL requirement and, although it doesn’t need funding from that perspective, it is keen to maintain rating stability. This means it must issue a defined amount of MREL issuance, predominantly with senior non-preferred, says LBBW’s head of asset and liability management, Patrick Steeg.

LBBW aims to optimise its funding across different currencies and instruments by taking account of new business, retail deposits, redemptions and other factors. “Based on that you can expect Pfandbriefe from LBBW next year,” says Steeg.

Like many euro area banks, LBBW took part in the third targeted long term refinancing operation (TLTRO III) in June, although this liquidity did not change the bank’s funding plan.

Indeed, after the June operation, in which €1.3tr was drawn by banks across Europe, many are likely to be close to reaching the maximum they can borrow which is capped at 50% of their eligible loan portfolio.

“I assume that for many banks the potential to increase TLTRO borrowings is limited after the massive participation in this June’s tranche and a limited amount of the eligible portfolio that’s on balance sheet,” says Bodo Winkler, head of long term funding and investor relations at Berlin Hyp.

Banks participating in June’s operation were provided funding for three years, while UK banks using the Bank of England’s Term funding Scheme for SMEs (TFSME) launched in March 2020 were given four year funding.

Both schemes offered favourable interest rates that were far cheaper than the next cheapest source of wholesale funding which is covered bonds. That led to a curtailment in issuance volume from €135bn in 2019 to €90bn in 2020.

However, the main drawback of these facilities is their short tenor, which does not match the natural duration of the mortgages that covered bonds fund. This is typically around six or seven years, while in the Netherlands mortgage loans are increasingly in the 20 year range. For this reason covered bonds will remain a key tool in the bank treasury’s funding arsenal.

“I expect some issuers to use covered bonds as a means to extend duration of cost-effective wholesale funding,” says Peter Green, head of senior funding and covered bonds at Lloyds Banking Group in London. “Covered bonds are expected to remain a core funding tool for issuers, especially as consideration turns to refinancing the alternative funding schemes.”

Cliff edge

When these central bank facilities mature and market funding is required, banks will face a refinancing cliff edge. This implies that some issuers will aim to smooth their debt liabilities by starting to repay central bank loans early, potentially up to 18 months before they mature.

In the case of TLTRO III this would initially have suggested that repayments and market funding would start around the second quarter of 2022. However, the ECB extended the TLTRO programme at its policy meeting on December 10, meaning that banks may now have less incentive to repay funds early and 2020’s low euro benchmark covered bond issuance of €90bn is likely to remain equally low in 2021.

Although the ECB will be hoping for a quick economic recovery it will fear the lasting impact of a recession and it will not want to see credit conditions tightening. “A vaccine is not a magic wand, meaning that a radical turnaround in peoples’ behaviour is unlikely,” says Danske’s Hubbard. “The ECB is likely to be very cautious to ensure yields and spreads stay low.”

In covered bonds that means the ECB is likely to maintain a tight grip on spreads with strong buying through its purchase programme (CBPP3), where it has been placing orders worth 40% of a new issue’s deal size, as well as buying even more aggressively in the secondary market.

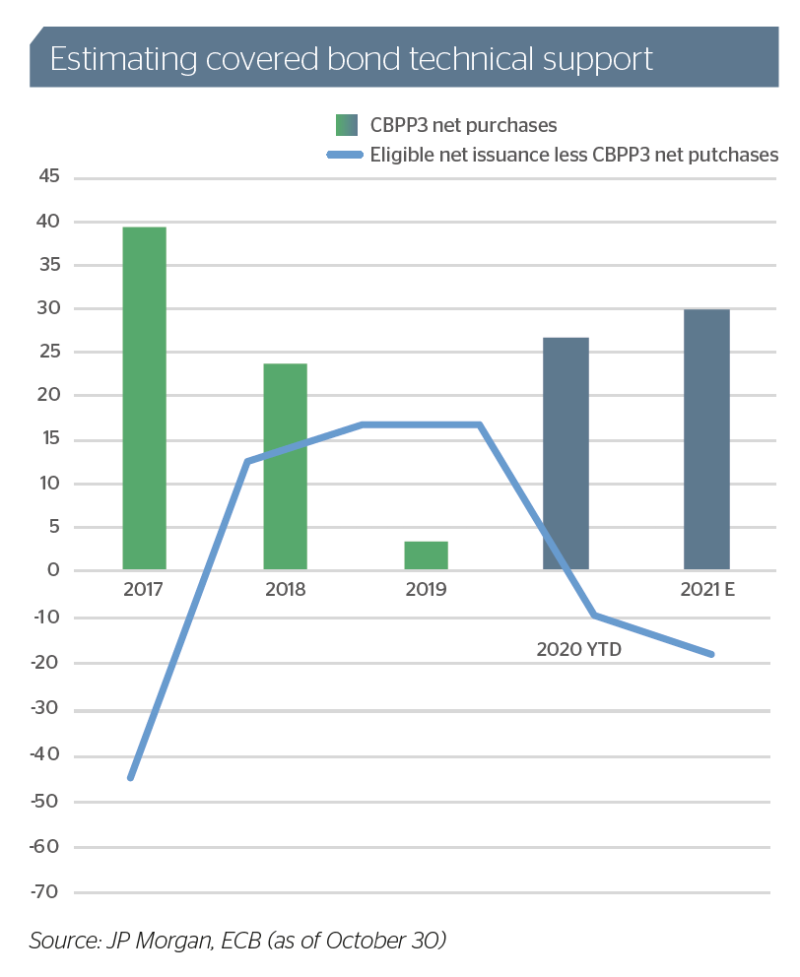

In the year ahead, the ECB is expected to make net purchases of about €30bn on top of replacing almost €28.8bn of redemptions from its CBPP3 holdings, according to JP Morgan research (see table). But with eligible covered bond issuance of €75bn, issuance net of purchases will be €36bn negative suggesting spreads will stay squeezed.

This will particularly be the case in the first half of the 2021 when overall euro covered bond redemptions will amount to a little over €130bn, almost 70% of which fall due in the first five months of the year.

“I’d expect a continued compression of the whole financial stack as the hunt for yield is here to stay,” says Armin Peter, head of global syndicate at UBS in London. But, with the vaccine being rolled out and natural immunity building there is a fair probability the global economy will show distinct signs of improving in the second half of 2021 when “you may see rates rise, opening up the possibility of shorter maturity buckets”.

Covered bond borrowers avoided issuing shorter than five year maturities in 2020, reflecting the fact that swap yields have hovered around minus 0.50% area, which detracts from demand and lowers deal execution certainty.

So, even a 20bp rise in short term yields would bring back investor demand, causing a marked shift in supply to shorter maturities. This is especially relevant to senior preferred bonds, where spreads for well rated banks trade with a low double-digit pick-up to mid-swaps and are therefore negative yielding.

But if the ECB were to increase the scope of its purchases and include the €276bn of outstanding senior preferred bonds, yields would remain firmly negative.

Though most bankers do not expect this to happen, Matthew Bailey, a European credit strategist at JP Morgan in London, offers another view. The historical reason for excluding senior preferred purchases was that they conflicted with the ECB’s role as the bank regulator, but Bailey says senior preferred should no longer need to be bailed-in under most scenarios and believes their risk is close to covered bonds. “If they [the ECB] wanted to get more size, this would also be the place to get it,” he says. GC