Capital markets players are convinced the US’s long wandering in the wilderness as the world’s chief renegade on climate change is coming to an end.

The election of Joe Biden as president — though without control of the Senate, barring great luck for the Democrats in January’s Georgia run-offs — has wrested power from the most aggressive enemy of climate policy among world leaders and given it to a candidate who knows the urgency of action.

“We’re excited about Biden making climate a central focus of his campaign, and we’ve seen important statements about his plans for his first 100 days,” says Kirsten Spalding, senior programme director at Ceres, the US responsible investment NGO, in San Francisco.

Biden has vowed to take the US back into the Paris Agreement “on day one”, set the US on course for net zero emissions in 2050 and push for more ambition from other countries. This will have profound implications for finance, both in the US and globally.

“We will now have all major economies with basically the same target — Japan, Korea, the EU are going for net zero in 2050,” says Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative. “The Chinese are basically the same — they’re saying 2060 but I think in 10 years they’ll upgrade to 2050. This is a massive shift in one year.”

Last chance saloon

The history of US climate policy is littered with false dawns. President Clinton signed the Kyoto Treaty in 1998 but the Senate refused to ratify it. Instead of taking the US in, President Obama tried to renegotiate it. Eventually he signed the Paris Agreement — only for President Trump to pull out.

Sustainable finance specialists are convinced it will be different this time. Above all, the climate is no longer a medium-term problem, but an immediate one. Governments around the world know it, and so do US citizens. Smoke from Californian wildfires reached Washington DC this summer. Biden has said “how we act or fail to act in the next 12 years will determine the very livability of our planet”.

Rejoining international climate diplomacy will be tricky. “The challenge for the US is its leadership rhetoric is rooted in the idea of American exceptionalism,” says Kidney. “I’m not sure that’s going to play as well any more. Trump has hacked back the US standing in the world. It will be interesting to see how they cope with Europe taking a strong lead and China’s green ambitions. There has to be a very different message. ‘We’re now here to save you’ is not going to work — it will create enemies.”

Encouragingly, though, Biden’s history of bipartisan collaboration in the Senate makes him ideal, Kidney argues — “a master of collegiate responses”.

And at least Biden will be jumping on a running horse, rather than trying to whip it to start.

“My network of 175 institutional investors are committed to working on sustainability, regardless of the administration,” says Spalding. “They are addressing climate as a core sustainability risk — it’s systemic. To have political support is important, but they are global investors — they were moving that way anyway.”

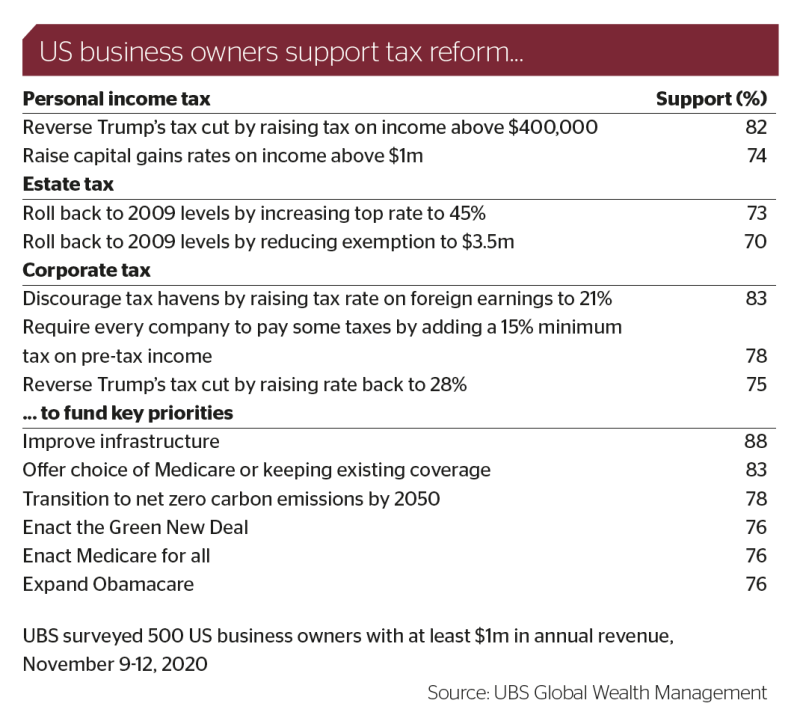

In a survey just after the election, UBS Global Wealth Management found that both business owners and rich private investors in the US strongly supported parts of Biden’s agenda. Remarkably, more than 70% of business owners agreed with raising taxes in seven different ways and nearly 80% approved of using the money to support the net zero transition.

No money

Nevertheless, in all likelihood, Biden will have to contend with a Republican-controlled Senate that tries to block his every move.

That will have two overriding effects. Policies that need federal spending will be difficult — including the $1.7tr of climate investments Biden promised.

“It’s all going to be about the 2022 midterms,” says James Jampel, founder of HITE Hedge Asset Management, a Boston hedge fund that trades only energy securities. “So he needs to be doing things that first and foremost are good politics. Unfortunately, the things that have most net effect on emissions will have to wait, because the politics are harder.” That means no carbon tax or ban on fracking, he argues.

But despite these constraints, there is much Biden will be able to do. He will steer all the government ministries and agencies, and will be able to change regulations through executive orders.

Easy wins would be buying electric vehicles for the postal service and military and persuading natural allies like Amazon, whose CEO, Jeff Bezos, often clashed with Trump, to electrify its fleet.

Obama regulated to raise new car efficiency from 25 miles a gallon in 2016 to 54 by 2026; Trump lowered this to 40 and, encouraged by General Motors, Fiat Chrysler and Toyota, tried to make it illegal for individual states to set higher standards.

That kind of active regression will cease. But rather than fight the car lobby to raise federal standards, Jampel says, “The key twist is to let California lead. When California sets a standard, all the car companies have got to meet that — they’ll say ‘we’re not building two types of cars’.”

In September, California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, signed an executive order requiring that all new cars sold in the state from 2035 be zero emission.

Trading on green

Actions like this will have immediate effects in financial markets, as investors reposition.

“Investors are pragmatic,” says Andrew Lee, head of sustainable and impact investing at UBS Global Wealth Management in New York. “They invest according to drivers and support from things they know affect investments.” In the firm’s post-election survey, 41% of investors said they planned to boost sustainable investing in the next six months.

Despite the US’s deeply divided politics, the impetus for a Green New Deal is gathering widespread support. Spalding expects more green and sustainable bonds to be issued, “especially around ‘build back better’”. She is working with local government treasuries, including California’s, that have pledged to issue green bonds to finance green infrastructure, which particularly benefits disadvantaged communities.

“On the investing side there are still questions — how do we verify? is there additionality?” she says, but issuers are enthusiastic. “Corporations making net zero commitments can use green bonds to meet them — they’ve got to start investing in new technologies, and green bonds are an obvious vehicle for that.”

Unblocking the markets

While these changes in the real economy will flow into the financial markets, there will also be efforts in the other direction — to green the economy by reforming the financial system.

“The recent vote in the US is catalytic, and will almost certainly come to be regarded as a turning point in climate finance, where we mobilise markets to deliver the Paris Agreement,” says Steve Waygood, chief responsible investment officer at Aviva Investors in London.

For four years, while many US investors have advanced in sustainable investing, the official sphere of regulation and supervision has been frozen in time.

It has begun to thaw incredibly fast. In the week after the election, the US Federal Reserve applied to join the Central Banks’ and Supervisors’ Network on Greening the Financial System — the influential group that includes the central banks of nearly all other large economies.

For the first time, the Fed also discussed the risks of climate change in its six-monthly Financial Stability Report. In an accompanying statement, Lael Brainard, one of the Fed governors, said: “It is vitally important to move from the recognition that climate change poses significant financial stability risks to the stage where the quantitative implications of those risks are appropriately assessed and addressed.”

The Fed is now likely to catch up fast with peers in countries such as the UK and France, which are planning climate stress tests for banks.

Shareholder rights at stake

Unlike the Fed, which has simply been silent on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues, the Securities and Exchange Commission in the past four years has been hostile, introducing a succession of measures that make it harder for investors to hold companies to account.

One of the most notorious made it on to the rulebook days after the election. It impedes small investors from proposing shareholder motions — though they often raise causes later joined by big investors. Even for motions backed by large funds, the SEC has said they cannot be presented again a second year unless they achieve a very high minimum threshold of support.

“There were no investors pushing for it — it was clearly coming from the issuer community,” says Heather Slavkin Corzo, head of US policy at the UN Principles for Responsible Investment in Washington.

Had the rule been in force in 2019, it would have banned a motion backed by 33% of Boeing shareholders after its 737 Max airliner crashes, that asked it to disclose more about its lobbying — a factor in the weak regulatory oversight partly blamed for the disasters.

Startling change

The about-turn at the SEC may be even sharper. Two days after the election, Allison Herren Lee, one of the two Democrat members of the five person Commission — which by law must be bipartisan — gave a speech about climate change, setting out why it was a threat to the financial system and how the SEC should regulate for “uniform, consistent and reliable disclosure” by companies and investors about the full range of ESG issues.

This should include, Lee said, requiring banks to publish the emissions of organisations and people they finance — something that, if carried out, would put the SEC ahead of other regulators on this issue.

Market participants believe there is a chance Lee might take over as chair of the SEC, temporarily or permanently, after Jay Clayton leaves at the end of the year. However, Republicans in Congress are expected to delay the appointment of a new permanent chair, as that would give Democrats a majority on the Commission.

High on the wish list for ESG enthusiasts will be overturning the shareholder vote rule, but Slavkin Corzo thinks “we are looking at at least one shareholder vote season with these rules”.

Even under Clayton, she says, “we saw the beginning of a process to review mutual fund naming rules and put guard rails up to make sure products claiming to be sustainable really are”.

An initiative with strong US roots is the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures — the private sector group led by Michael Bloomberg, the media entrepreneur, and Mary Schapiro, who chaired the SEC under Obama.

The TCFD guides companies and investors to declare, in their financial statements, how they are planning for climate change.

It is rapidly winning official support — the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority will require it for companies with premium listings on the London Stock Exchange from 2021.

So far, it has not had government backing in the US, but market participants expect that to change, perhaps before the COP 26 climate summit in November 2021.

“Mandatory TCFD for the US is an entry level step back into the global climate community,” says Ivan Frishberg, first vice-president of commercial banking at Amalgamated Bank in Washington.

Duty calls

Another important area where the US has fallen behind Europe is the thinking about investors’ responsibilities around ESG.

The US investment market contains world leaders in impact and activist ESG investing. But the mainstream is still getting to grips with ESG — it has not become ubiquitous as in Europe.

Asset managers in Europe have moved their collective mindset to regard considering ESG as part of their fiduciary duty to do the best for their clients. US firms are much more conscious of fiduciary duty as a potential constraint on ESG investing.

This is partly because regulations say so. Not for all investors, but the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (Erisa), which governs corporate pension plans, has a wider influence.

In the dying days of Trump’s authority, the Dept of Labor, which oversees Erisa, issued a new rule on how corporate pension funds can take into account ESG. The bizarre and confusing text does not ban ESG investing outright, but obliges funds to jump through hoops if they want to consider “non-pecuniary” factors.

This issue is always “ping-ponged” back and forth by Republican and Democratic administrations, says Frishberg. Usually they content themselves with interpreting the rules differently; Trump’s team went further by writing a new rule.

But Slavkin Corzo says they “left the ping-pong ball on the table” by “saying it’s possible to consider ESG issues as pecuniary”.

The new administration can issue interpretative guidance immediately. “We will advocate something that clarifies that ESG issues are pecuniary and fiduciaries have an obligation to consider them,” Slavkin Corzo says.

A greater advance, later in Biden’s term, would be a new rule that clarifies the definition of fiduciaries’ duties as including considering ESG issues and requires them to disclose how they do so.

The big prizes

Each of these pieces of reform would be cheered by sustainable finance supporters. But some hope for something bigger.

Slavkin Corzo has heard rumours from Biden’s transition team that there is a “desire to integrate climate more into the executive branch across the board”.

A really powerful outcome, she says, would be “if they were to make sure there were staff at all the regulatory agencies, from the Dept of Transportation to the Dept of the Interior, all trying to make sure the policies they were pursuing included a climate lens.”

A similarly broad approach could be applied to finance.

The Green New Deal, says Waygood at Aviva, will need private finance as well as public money. He points to the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan, which “sets out how Europe will mobilise markets”. Since 2018, the EU has corralled the freeform antics of Europe’s ESG investors into a discipline criss-crossed with regulations.

“We need the same thing in the US,” says Waygood.

Much of this is on the agenda. In commissioner Lee’s speech, she tentatively raised questions about whether the SEC should regulate the ESG claims of funds, how credit rating agencies apply ESG criteria and whether the Financial Accounting Standards Board should follow its international counterpart and set out how climate-related risks should be reflected in financial statements.

The centrepiece of the EU plan is its Taxonomy of Sustainable Economic Activities — an encyclopaedia of what can officially be called sustainable, for financial purposes. Canada is now writing its own taxonomy, friendlier to natural resource industries. Both the EU and Canada want to broaden their work into an international taxonomy.

“We would like the US to get involved in the taxonomy work,” says Kidney. “I’m modestly optimistic, but I don’t think it will be fast, because there’s too much domestic work to do.”

This is one example of how the US could come in from the cold and quickly start contributing to greening the international financial system.

“The US is an incredibly influential member of all the world’s global regulatory financial institutions,” says Waygood. “Its role there could be brought forward very positively. It’s also the domicile for the largest credit rating agencies, investment banks, fund managers and investment consultants and hosts the two largest proxy voting agencies.”

Particularly important is the US’s influence at the G20’s Financial Stability Board, which created the TCFD. Biden could allow the FSB to go further, and especially to work with the International Accounting Standards Board towards fully integrating ESG issues into accounting for the first time.

“The Biden transition team should be thinking about how to devise a plan to ensure the US has a defining, leading role,” says Waygood. “Otherwise, US financial institutions will be left behind.” GC