Enthusiasts for the eurozone's capital markets are excited that the US's whipsawing trade policies might be bringing the dollar's overwhelming dominance of global financial markets to an end.

That is wishful thinking. But even if euro markets can nibble at the edges of dollar hegemony, it will be a huge win for euro bonds.

Maybe US president Donald Trump has a grand plan that most people can't see with his swingeing trade tariffs, but, as of now, the consensus is that the tariffs will do more harm than good to the US's economy and global reputation.

This has made many in Europe’s fixed income markets giddy with hope of the euro challenging the dollar's supremacy.

For bond markets, the ascendancy of the euro would mean investors choosing to put more of their money into euro rates products over Treasuries, and, the hope goes, eventually into less liquid and ostensibly riskier markets such as European credit.

This would be a huge boon for all parts of eurozone bond markets.

More investor money coursing through the system would be likely to mean more days available on which to print debt. Unlike the euro bond market, its bigger dollar cousin is almost always open.

It could also give issuers more leeway to push hard on pricing, and support a more liquid secondary market.

For reference, see how easy market conditions were for issuers during the European Central Bank's roughly 10 years of quantitative easing.

Hold on now

Sadly, this windfall for the euro won’t happen — at least not to the extent eurozone regulators and bond market participants hope it will.

The biggest problem is that the same consensual decision making that helps keep the European Union stable also keeps it slow.

The EU's drive for a Capital Markets Union ran for a decade before being rebranded as the Savings and Investment Union, yet the achievements of the CMU in all that time are negligible.

The CMU is a microcosm of the way the EU approaches new financial opportunities — at the speed of continental drift.

In the US, Trump’s absolute hold over the House and the Senate could end in November 2026’s mid-term elections, and the scale of the ‘No Kings’ protests in many US cities last weekend suggests that anti-Trump grassroot politics are mobilising.

That means the EU may have little time to sit on its hands if it wants to grab some of the dollar action. But inertia is built in, because getting a majority of 27 countries to agree on something is like herding cats.

A little is all you need

All is not lost for Europe, however. Even if the eurozone can shave a small sliver off the US's outsized share of the pie, it will make a big difference to European bond markets.

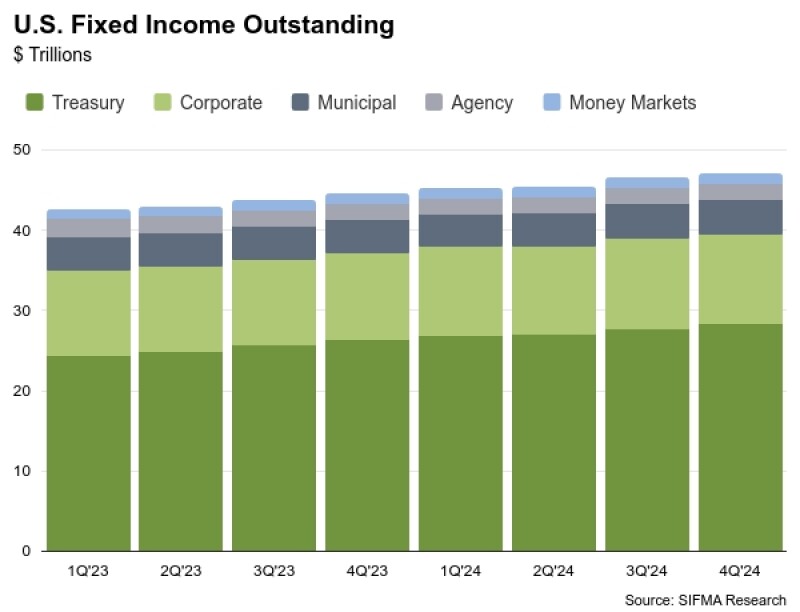

The Treasury market, for example, has $28tr outstanding as of the end of May this year, according to Sifma Research. Germany's Bund has roughly €1.9tr outstanding. The sizes are almost incomparable.

There is already anecdotal evidence of investors switching from dollars to euro fixed income.

Bank syndicate desks say they are getting investors in books that either they have not seen before, or are coming in with tickets much bigger than they would previously buy in euros.

The nature of the fixed income markets — their size and the wide range of investors involved — means the data to support these claims will not be available for months.

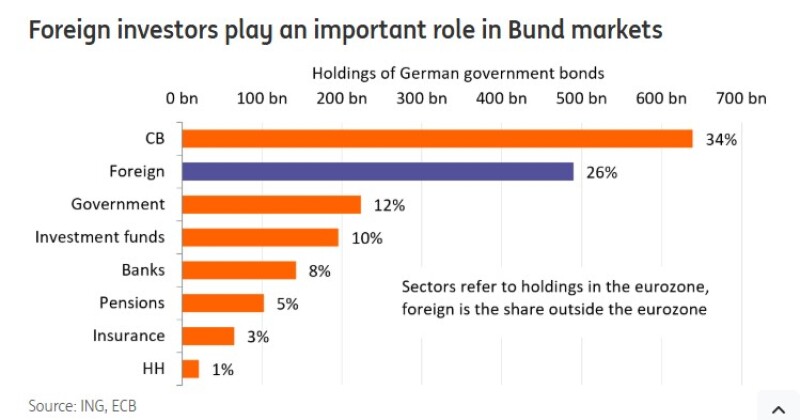

But investors outside the eurozone held 26% of Bunds as of May this year, according to ING (see graph left). That statistic will be well worth keeping a close watch on over the next 12 months.

Even if mobile investors shift 5% of their Treasury allocations to the eurozone, that could send hundreds of billions more cash into Europe to fight for bonds — pretty useful at a time when countries led by Germany are planning a big increase in spending on defence and infrastructure.

If investors' fear of Trump’s policies persist, even just at the edges, then it still has the power to reshape the eurozone fixed income markets for the better.