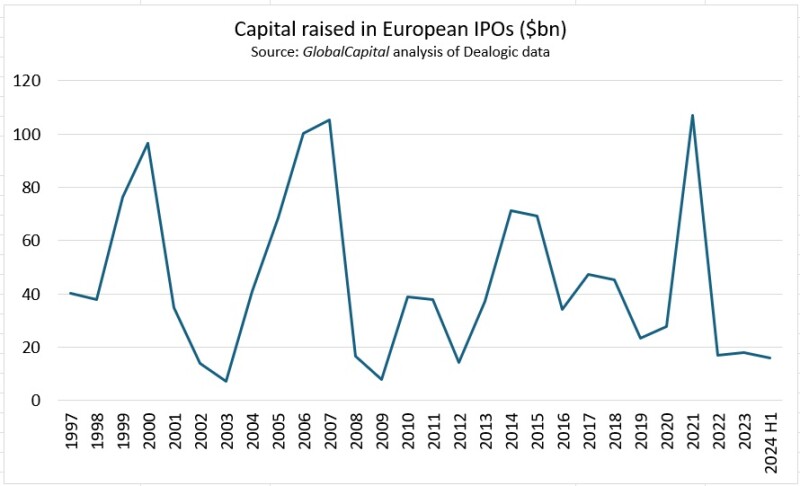

Europe’s IPO market is broken. People have said it before, only to look ridiculous later when the market roared back to apparent health. Like in 2011, before the 2014-15 listings boom.

But for one of Europe’s most fundamental capital markets to be as outlandishly cyclical as this cannot be optimal.

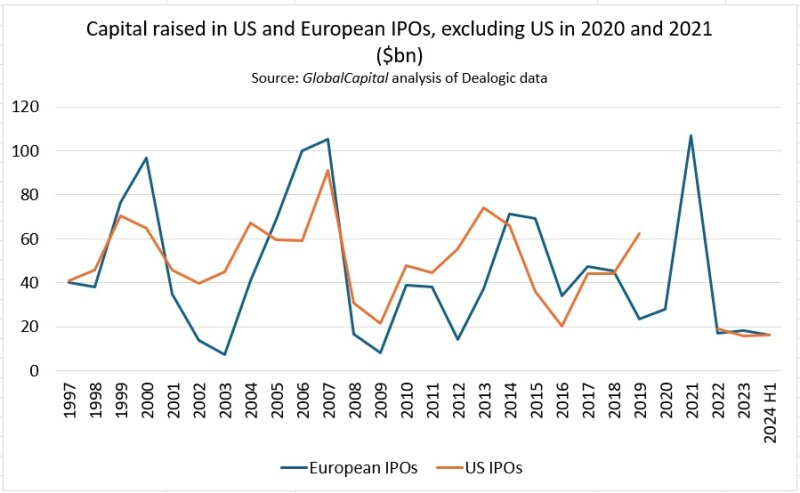

The US market is also bumpy, but less than Europe’s, as shown on this graph, which leaves out the two extreme boom years of US funds and Spacs in 2020 and 2021.

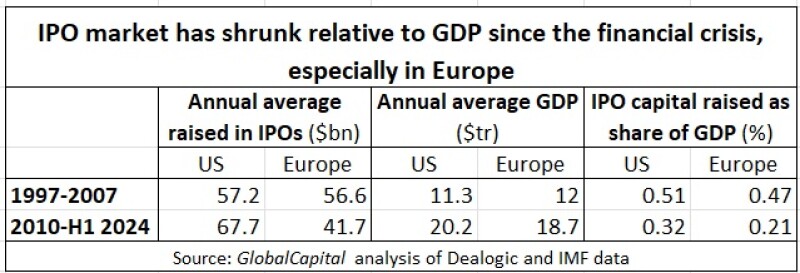

But it is when you layer in the growth of the economy that you really see how the IPO markets have dwindled.

Perhaps we should just give up on IPOs ― accept that private equity is now the most dynamic and prolific form of growth company investing and stop worrying about flotations. Private ownership is also now often the solution for unloved businesses, as well as the exciting developers of new technology.

But that is a dead end. If the public equity market did not exist, someone would have to invent it. It is by far the most efficient and barrier-free way for any and all investors to allocate capital to any company that chooses to make itself available.

PE firms use the stockmarket as a barometer of valuation, an outlet for assets they have finished with, and a supermarket to raid when they are hungry for something new.

Something wrong

If there is a public market, there has to be a way of entering it, so why is that so problematic?

“European IPOs are the least efficient capital market,” said one observer recently. “There’s a failure rate of about 30%.” And that was from one of its major investors.

Permira’s last minute decision to pull the €600m IPO of luxury trainer maker Golden Goose on June 19 was just the latest disappointment.

It prompted Craig Coben, former global head of equity capital markets at Bank of America, to arraign in his GlobalCapital column a market in which banks give out true, but ultimately meaningless information on how an IPO is going.

In this case, they said Golden Goose was multiple times covered, when the book did not contain enough solid, long-only orders for Permira to feel it could safely close the deal, without fear of it tanking in the aftermarket.

“It’s easier to state the problem than to resolve it,” wrote Coben. “But somehow the industry has to find a way to restore meaning to market communication.”

What's in the book?

The marsh of misunderstanding Coben was specifically lamenting is the updates banks give about how a book is building.

It is possible to suggest some ways to resolve this problem.

Underwriters use a tiny, stilted vocabulary of clichés to describe the book’s evolution. They talk about the IPO being “covered” at a certain price, sometimes “multiple times”, or that it is covered “throughout the range”. As everyone knows, this almost never means it gets priced at the top.

What really matters is the deal team’s hidden, private assessments of how solid or squishy each order is ― a moving target, since the behaviour of the investors is keenly influenced by how each other behave.

IPOs at the moment are like a perilous masked ball, in which ingénues mingle with mysterious cloaked figures who circle each other by candlelight, and the threat of treachery hangs in the air.

The solution seems obvious, if painful to an industry unused to it: transparency.

How much better would it be if investors knew, not just that the book was “multiple times” covered, but exactly how big it was?

If they knew how much demand was from long-onlies, how much from hedge funds? If they knew the number and range of sizes of orders from each group? If they were told the price sensitivities?

It seems shocking, because so different from what is done now. But these things are all possible.

No disguises

Go one step further ― run an IPO in which investors reveal their names when they put in orders.

Cries of horror will greet this idea ― critics will say it opens up scope for cynical traders to take advantage of market knowledge about investors’ positions.

But isn’t that happening already? Indeed, isn’t that the actual problem with IPOs?

To claim that forcing investors to reveal their bets ― whether by name or described anonymously by category and size ― infringes their commercial rights is a straw man. No investor is forced to go into an IPO ― participating would be voluntary.

Many experts no doubt have better ideas on how this could be managed. But it seems clear that the answer must be to move towards more transparency on books.

Nasty maelstrom

That is so for the same reason that the cure to Europe’s IPO problems is not to lower corporate governance standards: what puts investors off IPOs is fear of losing money.

Inevitably, they are afraid because they are buying a new company, whose behaviour they are not familiar with. Investors can reduce that uncertainty by studying the company, with the help of research, meeting the company’s management, visiting its premises, asking questions.

GlobalCapital has previously suggested using a system of independent ratings for IPOs to give investors more clarity on the company's risks.

But as things stand, investors also face another huge swirl of danger. Even if they like and trust the company, they have to go through the viper’s nest of an IPO, in which specialist investors trying to make a quick buck cluster round the deal, eager to catch a juicy pop, but just as ready to dump the stock if it looks like a loser.

As one head of ECM said recently: “Europe tends to be very binary ― it’s either up 20% or down 20%. If it’s going to trade up everyone gets behind it, and if it’s going to trade down they get out. You don’t get down 5%.”

The present IPO system is a machine for generating volatility.

Get to the root

Clearer information on the book is desired so that participants have a better chance of gauging whether this deal is going to burst up or down.

But if that is the all-important issue, it raises the deeper question: why tolerate this investor behaviour?

‘Hedge funds’ is a broad category, incorporating many investment styles, and not all short-termist investors are hedge funds.

But if there is a large, identifiable group of investors that investment banks know very well are not interested in holding the stock for the long term, and are liable to sell it as soon as look at it, why have them in the deal?

The standard answer is that “you need hedge funds in the deal for liquidity in the aftermarket”.

Be for real. Is that liquidity worth having? Or isn’t it the other way round ― the hedge funds need the real money accounts as stuffees.

As the ECM head said: “the deals [hedge funds] want to be in are the ones where they know where the long-only bid is, because they’re going to be selling to it.”

The typical IPO allocation of around 25% or 30% to hedge funds and another few percent to family offices and private banks (also not considered pukka long-onlies) is fine ― for a deal in which everything goes right.

The stock is hot, investors are eager for it, and in the aftermarket they want to buy more. The hedge funds harvest a short-term profit and supply more stock to long-onlies that don’t play IPOs or didn’t get as much stock as they wanted in the bookbuild.

Lovely when it happens. But the IPO market is miles from being in a state where the majority of deals can have any reasonable confidence of achieving such an outcome.

Shallow pool

Despite a strong economy and a bull market for shares, up 47% in Europe since the recent trough in September 2022, just a trickle of companies is coming to market.

It is perfectly clear that the European IPO market’s main problem ― the reason why it is so inconsistent and over-sensitive to the slightest political or economic breeze ― is that only a small fraction of investors is willing to participate.

Why will so few mainstream investors buy IPOs? They are scared of the volatility that surrounds them.

There will always be a risk with an IPO that it can fall on debut, or in the days, weeks and months that follow. It tends to be held by a few hands, which have no loyalty and are easily discouraged. At the same time, there is a chance of quick gains.

This inherent characteristic attracts short-term investors, who exacerbate this very volatility. The vicious circle of a narrow investor base drawing short-termist players, which scare off humbler, more fundamentally driven funds, has twisted this market for too long.

Stick with the goodies

If investors that actively want to flog the stock quickly are the problem, and having accurate information about their influence is the central information question about a bookbuild, then why allow the IPO-flippers into the book in the first place?

Bankers on and off the deal said the fate of Golden Goose hung on how much strong long-only demand there was, relative to the deal size.

So they admit the three times oversubscription by hedge funds was just noise at best ― irrelevant to the deal’s success, and perhaps even a hindrance.

Just leave them out, then.

So there will be less liquidity in the aftermarket ― but bankers scorn the idea that there is much anyway.

Long-only investors who retain faith in the deal will hold on to it ― and if they lose faith, hedge funds are not going to rescue them. If a thinner aftermarket makes it harder for long-onlies to increase their positions, so be it ― the stock should rise, more gradually but perhaps more reliably.

Look north

All of this is only to suggest the wider and more systematic use of techniques that are already employed in the market.

Cornerstone investors are already used, especially for riskier deals or in weaker market conditions ― investors that are willing to reveal their names and the sizes of their orders.

Why should this not be more common? Disclosure need not require the irrevocability that typically goes with cornerstoning.

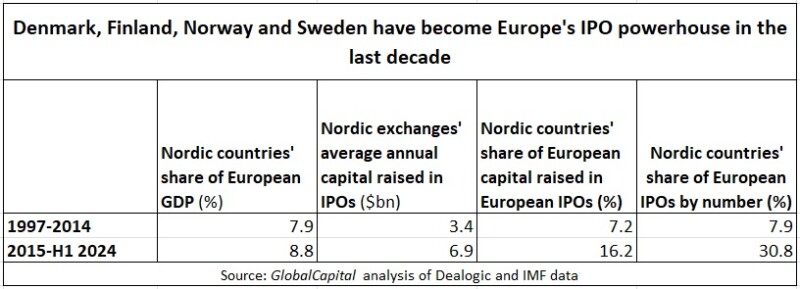

As is well known, the Nordic region, especially Sweden and Norway, punches far above its weight in IPOs, with a stunning 785 completed in the past nine and a half years in those countries plus Denmark and Finland. Cornerstones often feature ― and this region also has a lively private equity culture.

Trying to establish individual investors’ intentions and commitment to the stock is already part of what investment banks do in an IPO. Long-onlies are already preferred over hedge funds in allocations.

Go with the flow

At a deeper level, changing IPOs in this way chimes with the economy-wide shift to private equity ownership, and the growth in private, pre-IPO funding rounds for growth companies ― a halfway house between private and public equity.

Equity holding is becoming less liquid, more structured and negotiated.

There still needs to be a transparent, public, liquid market. But the shore of that market, where companies pass from the private land into the liquid ocean, is at the moment a cliff.

It needs steps, to make that passage safer, less slippery and rocky. What every company floating wants is a group of investors enthusiastic about the business, wanting to support it into the medium term, and willing to tolerate fluctuations in the share price as long as the company’s performance remains on track. It does not need pirates who want to use it as a toy.

Transferring ownership to a selected, desirable group of new holders, with greater capacity to trade the shares, needs to be calmed down, derisked, made more predictable and reliable. More scope for the underwriters to manage the flows of stock in the first weeks after listing could also be useful.

A steadier process will encourage more long-only investors to come in, reducing the market’s reliance on the bigger players, and making books more granular.

The idea that a floating company plunges instantly into perfect liquidity is not only false, but harmful. It encourages all the instincts and urges that have made IPOs so hard to execute.

The IPO as riotous party may be fun for hedge funds and investment banks, but it needs to go. Bring in the church fête, by invitation only.