The boom in private credit in the last few years has led to many wondering what could possibly stop this exciting new market. The answer is probably M&A.

Late last year, investment goliath BlackRock predicted the global private debt market would double in size to $3.5tr by 2028.

Some of this will be the company talking up its own book. BlackRock, like many others, has turned to private credit as higher interest rates turned boring old loans into something that could provide a decent return as a standalone product.

The already overbanked European syndicated loan market has noticed the influx of new money, especially at the lower end of the ratings spectrum and into leveraged finance.

If you’re a borrower, private credit is a no-brainer. It’s quicker to arrange than syndicated finance, requires less disclosure to banks, and private credit lenders rarely, if ever, insist on ancillary business to make up for the cheap loan they’re giving you.

The flip side is that private credit lenders charge borrowers more than banks, to compensate for the single counterparty risk they are taking, as well as the illiquidity of the loan.

This extra risk looks ripe for a blow-up in the private credit market. If a traditional lending house provides a €200m loan, it can syndicate that if it is uncomfortable with the risk. The reward for the bank will be lower, but so will the downside if the borrower defaults.

In private credit, no such luxury exists for the lenders. They are stuck with the risk.

Multiple private credit providers have said over the last year that they are not worried about this. They roll off impressive sounding ideals such as the private nature of a deal allowing them a more forensic understanding of the borrower’s balance sheet than a mere relationship bank. Many private credit lenders also say that they only lend to “investment grade equivalent” companies.

This does not stack up with what loans bankers are seeing, nor with logic. Truly investment grade companies earned that status in part because of the easy access they have to bank finance. If a company is looking to private credit - particularly if it is looking for size - it is unlikely to be what mainstream lenders, or much of the market, considers to be truly investment grade.

This leaves private credit on the hook in a big way with a credit that might not be as good as implied.

A new development is only going to exacerbate this already risky situation.

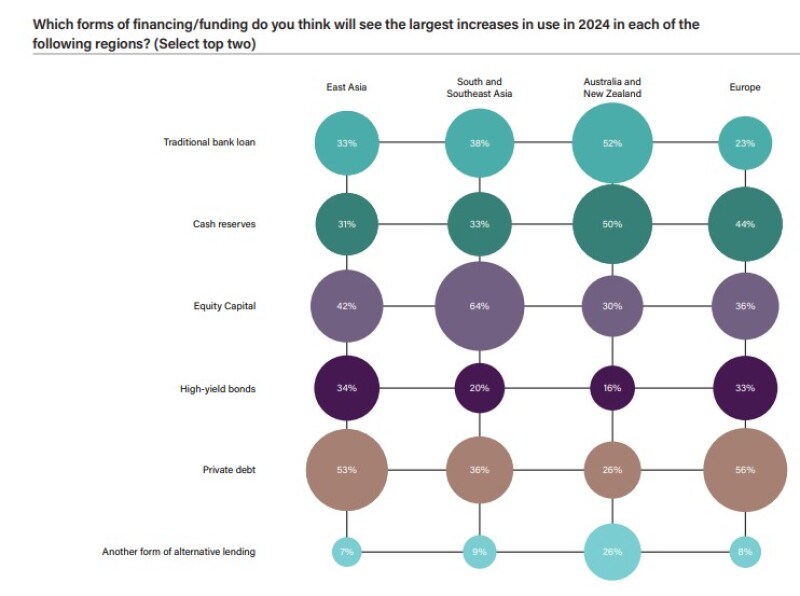

A survey by law firm Norton Rose Fulbright and M&A information provider Mergermarket found that, globally this year, 91% of respondents expect acquisitive companies to use private credit to finance acquisitions.

(Source: Norton Rose Fulbright/Mergermarket)

M&A is rife with difficulties, all of which the initial financing package has to weather because it will be in place when the buyer makes public its intentions. Shareholders could reject a deal, as could regulators. A sale price agreed by all parties might never materialise. Another company could swoop in and buy the asset with a better offer. The list goes on and that's all before the company has to integrate its purchase and run it profitably.

For banks, providing a multibillion euro bridge loan between a small group of two or three is risky enough, even with the tried and tested route to refinance that loan via the bond market. For private credit providers, which are most likely financing companies with less than stellar credit metrics and more limited access to bond markets despite what many insist, the risk is enormous.

If one deal goes bad, and it’s a big one tied to M&A, it could put a huge dent in the appetite to provide private credit. It is only a matter of time.