European bond investors have been pushing this year for corporate issuers to head out to 15 or 20 year maturities, but they have so far shied away, unwilling to pay higher costs. This week, the case for going longer became much stronger.

It is easy to see why investors want long bonds. Rates are expected to flatline and start falling this year, meaning now is a rare chance for high grade corporate bond buyers to lock in the highest yields possible, for as long as possible, before they come down.

The flip side is companies are hesitant to tie themselves to those higher yields for 15 to 20 years.

But this week proved just how difficult it is to judge when rates might fall. In the UK, December inflation came in at a surprisingly high 4%.

Meanwhile, European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde told Bloomberg TV that the bank would only have the necessary information on wage inflation by late spring, dashing hopes for a first half rate cut. Minutes from its December meeting, released this week, also show the Bank is far from even discussing rate cuts.

This should tip the scales for companies towards selling long maturity debt, as now there is little certainty that rates are going anywhere beneficial for borrowers. If anything, the higher than expected inflation in the UK puts a slight upward pressure on rates.

Yet investors are still avidly buying duration. This means that, relative to comparables and the rest of their curves, long bonds could prove economically logical for companies, even if the absolute yield is at 10 year highs.

The format does not suit every issuer. Companies that issue one or two small benchmarks a year would see their overall cost of funding rocket if one of those deals was a 20 year yielding more than 6%.

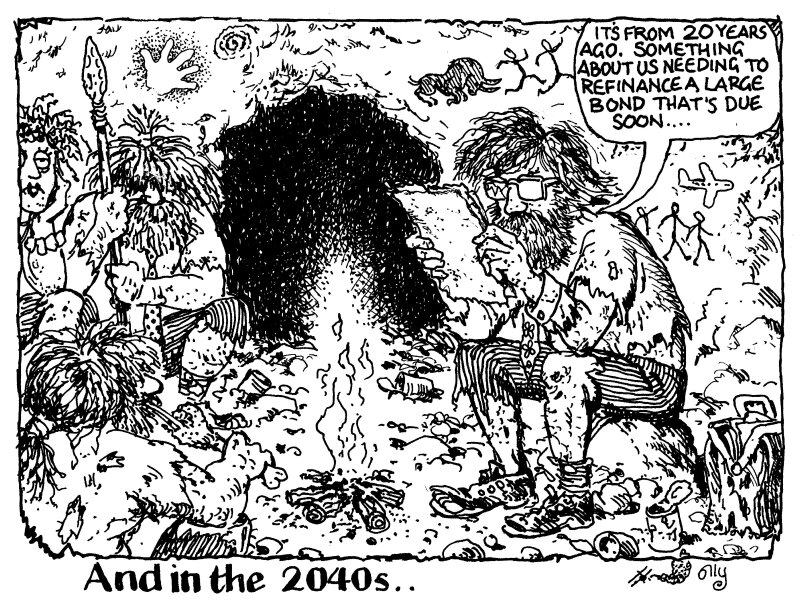

But for top rated borrowers with big funding programmes, the yield needed to secure long maturity debt can be smoothed out by the overall size of the debt stack, while the company gets to shunt refinancing risk on some of its debt into the 2040s.

It’s a fine balancing act, but one that this week’s macroeconomic shade has swung in favour of printing long.