The perceived decline of stockmarkets in Europe, and particularly the UK, is attracting an intellectual ferment of ideas to revive them.

A blog post by UK stockbroker Peel Hunt in August highlighted at least five strands of regulatory review and reform going on in the country, and proposed a dozen other measures that could help, from lower corporation tax for smaller companies to setting up a UK sovereign wealth fund.

The attention and creativity being invested in the problem is welcome, since the decline of public equities in general, and of company flotations in particular, is certainly concerning.

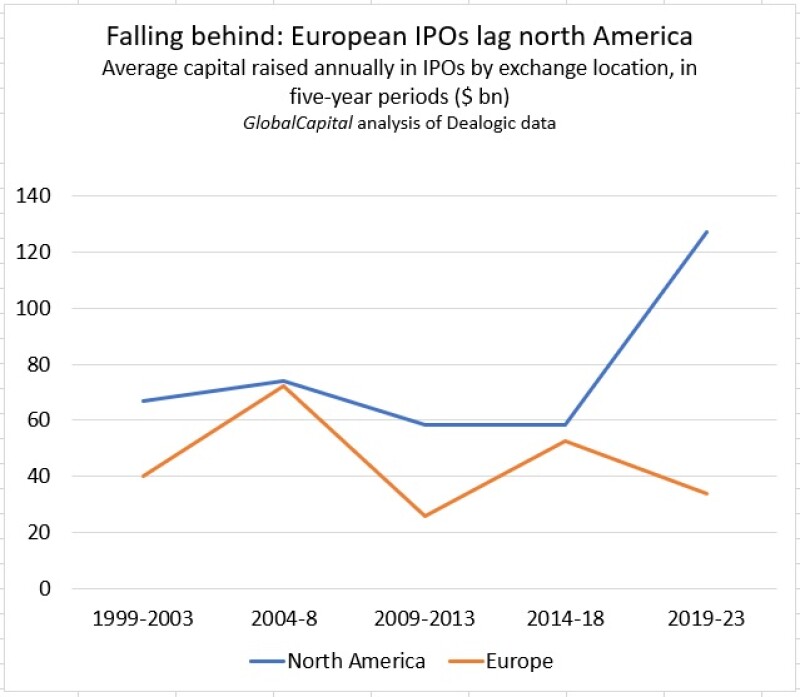

GlobalCapital analysis of Dealogic data shows that over the past 25 years, $1.1tr has been raised in IPOs on European exchanges (including the UK, of course), against $1.9tr on those in north America.

That 58% ratio in itself might not be concerning. The economies are roughly the same size, but that of the US has long been much more financialised.

Its society is more unequal, meaning there is more concentrated wealth. That, combined with the US’s deepseated culture of entrepreneurialism and personal investing, has enabled its stockmarket capitalisation to swell to 43% of the world’s total of $109tr, according to Visual Capitalist, using data from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

The EU has 11% and the UK 2.9%, little more than Canada’s 2.7%, though the UK’s population is 75% bigger. China and Hong Kong together have 14.6%.

What is alarming capital market participants, politicians and the media is that Europe is falling farther behind.

For most of this century, Europe’s IPO market has followed similar cycles to that in north America, though never quite matching it. But in the last five years it has gone in the opposite direction. The US enjoyed an unprecedented boom in listings ― Europe slumped.

Big is beautiful

Many reasons have been suggested, and many remedies, some easy to implement, others much more difficult.

A few elephants in the room are worth mentioning. Bankers and issuers always refer to the US as “the biggest capital market in the world”.

That is partly because it’s unified. All the participants are under essentially one legal system and trading together on two dominant stock exchanges, backed up by huge listed equity derivatives markets. The amount of money in the market is not only large, it’s accessible all at once.

Unity does not generate size of itself, and the harm done by disunity can be exaggerated.

Supporters of the European Union’s Capital Markets Union, for example, often make it sound like companies in one member state cannot raise capital from others. In fact, some of the EU’s capital markets, like institutional bonds and syndicated loans, are fully integrated across the continent ― a company from Portugal can borrow from institutions in Finland or the UK as easily as from a bank or pension fund down the road.

In equities, most large fund managers serving most savers, certainly in Europe’s advanced economies, can invest on most of the large exchanges. One wonders sometimes why so much fuss is made about where companies list. The pool of investors they will address, especially in the IPO itself, will essentially be the same whether they choose London, Paris, Amsterdam, Frankfurt or Madrid.

However, in equities there are still rigidities and barriers ― national preferences and loyalties, legal and operational wrinkles that mean UK savers, for example, are less likely to hold shares from Austria or Poland than the UK. This is especially true of small cap equities.

This divided structure is not mere bureaucratic obstruction. It reflects the fact that Sweden and Belgium are different economies, with different societies and legal systems. For one thing, unlike the US, a large chunk of Europe consists of emerging markets.

But there is undoubtedly a cost for this. Europe’s investment pools and venues are fragmented, which causes friction to capital flows.

As important as the actual cash available to invest, for example in an IPO, is the perception. The US has more money invested in equities, but it’s also very visible because it’s concentrated. It’s hard to blame companies like UK chip maker Arm and Irish building materials group CRH for choosing to list in the US: they simply want to swim in the biggest pond.

One for all and all for one

Should Europe unify its equity markets? For a time it looked like this was happening. From 2000 Euronext combined the operators of the French, Belgian, Dutch and Portuguese markets, and several times, before and during its ownership by NYSE, it nearly merged with Deutsche Börse. In 2012 a deal was blocked by the European Commission, which was worried about a derivatives monopoly. Since then Euronext has added Dublin, Oslo and Milan.

The Euronext model enables countries to retain their own exchanges and regulation, but benefit from the efficiency of harmonised systems. Other mergers have taken place, such as Vienna and Prague.

But Euronext has not become, and is not perceived as, one single stock exchange.

From a pure capital markets perspective, further integration, both into Euronext and within it, might well be desirable, but this is very hard to drive politically.

Exchanges are private sector organisations, and cannot be commanded to merge. Amalgamating everything could stifle competition in running exchanges and lead to stagnation.

Above all, many countries are likely to be reluctant to give up their own exchanges ― they quite rightly see having one as a pillar of economic sovereignty. That, after all, is the very same motivation that makes Europeans want to keep their companies listed in Europe.

The UK in particular has painted itself into a corner. Market participants wringing their hands about the decay of UK capital markets tend not to mention Brexit ― there’s no point. But when the country has wilfully split its markets from the much bigger ones they ought to be integrating with, no one should be surprised business is migrating to the US, or the continent.

Going private

Since progress on the central problem ― making Europe’s market bigger and more unified ― is difficult, market participants and policymakers must consider lesser measures that could help round the edges.

If ‘de-equitisation’ is a problem, there is no time to lose. Peel Hunt says the UK has lost a fifth of its listed companies in the past five years, and at times it has been bested as Europe’s largest market by Paris.

The migration of companies to the US, and of investment dollars to continental Europe, is worrying for the UK. But a much bigger trend is towards private equity ownership.

Invest Europe, formerly the European Private Equity and Venture Capital Association, does not have a figure for 2023 yet, but in 2019-22 it counted €467bn of private equity investments in Europe.

In the same four years, the amount raised in IPOs on European exchanges was €158bn.

Quite simply, the way European savers own equities is changing. More and more, the reshaping of companies ― buying and selling assets, trying out new strategies ― is being done by managements accountable not to the public market, but to private equity owners.

The case for them is that, away from the glare of publicity and having to worry about how the market will take each quarter’s results, companies can take better, more strategic decisions.

However, PE firms’ investment horizons are not long term. They typically like to get in and out in three to five years, and of course, juice up their returns with leverage. There is a limit to how many times a company can be handed from one PE firm to another, and make all of them double digit annual returns.

Public market investors are not locked in like PE firms ― they could sell out any day. But in practice, many tend to hold stocks for long periods, sometimes decades. And the transparency and accessibility that come with public listing should increase the chance that companies end up being owned by investors that really want them.

There is a strong case, therefore, that Europe needs a healthy and vibrant public stockmarket, even if private equity is now firmly and permanently established on the scene.

If the public market is bleeding companies, several possible explanations are obvious. PE firms use a lot of debt, which is tax-advantaged over equity.

Their fund and fee structures mean Europe's pension funds and insurance companies are paying PE managers much more generously than public equity fund managers. The well paid group is incentivised and tooled up to go and buy companies from the poorly paid lot. No wonder they succeed.

A wide variety of measures, including tax and regulation changes, has been put forward to redress the balance, as the public side would see it. Economic purists will worry these could distort markets and have unintended consequences.

The heart of the problem

But one aspect of the public equity markets is particularly in need of repair, and that is IPOs.

Other aspects of equity capital markets ― such as follow-on capital raisings and block trades ― generally work well. Even in weakish markets, deals can get done.

European equity investors, then, are not afraid to take risk. Often they will put up capital or buy into rights issues for companies that clearly have serious problems.

But the new listings market is absurdly fragile. This year there have been just €10bn of deals on European exchanges. London has hosted only one proper IPO, of emerging markets currency dealer CAB Payments in July ― it has been a disaster, the shares down 80%. Umpteen other deals have been pulled or postponed, at various stages in their approaches to the market.

In Europe, unless everything is right ― the company, the price, the market conditions, the mood and positioning of investors ― there is simply no IPO market.

This cannot be satisfactory for what ought to be one of Europe’s core capital markets ― the only route for private companies to join the public equity market.

The overriding problem appears to be that there are too few investors. Only a small minority of funds in Europe buy IPOs, and the market overwhelmingly relies on a tiny coterie of leading fund houses. If a deal doesn’t get the support of enough of these 20-odd big players, it is no dice.

This means that if these firms are feeling risk-averse, or in a bad mood because another IPO has performed badly, the market is paralysed.

Bankers and policymakers should apply themselves to working out what could be done to expand the investor base for IPOs.

A market that works

Leaving aside any form of compulsion, which is fraught with danger, IPOs have to be made more accessible and more attractive.

ECM bankers often look longingly at the US, where they say deals are done more quickly, without such laborious preparation, making them less exposed to the risk of the market tumbling during the sale.

But hurrying deals along really amounts to making them cheaper ― hardly loyal service to the company owners that pay the banks’ fees, or likely to attract more companies to list.

And if the seller hopes to flog the shares swiftly before the market falls, that merely shoves off the risk to investors. Investors surely need more information about companies and time to digest it, not less.

UK regulators’ notions of competing with the US by weakening corporate governance standards and investors’ rights are equally wrong-headed. For the sake of a tiny quantum of IPOs, they would taint the quality of the whole market ― and only increase the fear of the unknown that makes investors shy away from IPOs.

Over in the debt market, these same investing institutions support a much more reliable market. Granted, equity is a much riskier product. But leveraged finance deals channel plenty of risk. Investors routinely evaluate and buy into new companies they have not seen before, or ones whose capital structure and commercial prospects have changed markedly in the past few years. These firms often have tricky business models and aggressive owners.

Yet even in bad years, European leveraged finance keeps chugging through at least some business.

Why can fund managers take a hard-headed, but pragmatic view on, say, a leveraged loan for a Finnish equipment leasing company, but not the IPO of a Turkish soda ash producer (WE Soda, whose London IPO had to be pulled this year)?

A map for the maze

What makes leveraged finance possible is credit ratings. Three major rating agencies, venerable and grudgingly respected by investors, analyse the companies and produce conclusions that are accessible, easy to read, follow consistent, transparent methodologies, are comparable one with another, and are distilled into soundbites: the ratings themselves.

Investors who follow them will still make some mistakes. But ratings are a pretty good guidebook to navigating the world of credit.

Why doesn’t the equity market have anything like this?

Equity researchers are highly skilled, professional analysts, who contribute enormously to the market’s functioning. And they are attempting something more difficult than credit analysts: the question is not just the binary one ‘will the company fail?’ but ‘how well will it succeed?’

But, even after Mifid II and other reforms, the fact that most analysts still work for investment banks inevitably diminishes the trust investors will place in them.

This is particularly the case at IPOs, when the banks are usually selling a company the investors don’t know, and have a huge incentive to get the deal done. Even if IPO research is impeccably independent, if investors don’t believe it is, it can be much less influential.

Reforms such as unbundling and UK IPO rule changes have opened more space for independent research, either from other banks or a new breed of specialist firms that are paid by the issuers, like credit rating agencies. But these have not developed into a strong alternative to sell side research.

If the equity market could have some equivalent of Moody’s, S&P and Fitch ― independent and unbiased, giving structured and standardised opinions covering the important aspects of each company ― how much easier it would be for the broad mass of investors to consider stocks, and especially IPOs.

Of course equity research is more uncertain than credit research, and the rating agencies would be wrong more often.

But they could helpfully break down the problem ― give opinions on the likely path of cashflows, dividends, debt; score the competition risk the company faces and the technology and regulatory risks.

Investors know they are taking a risk when they buy any stock, but they want to know what kind of risk, to be able to think about it in an educated way. The rating agencies are good at filling that gap for credit, and someone could do it for equity.

The equity ratings would not even need to give share price targets and 'Buy', 'Hold' or 'Sell' recommendations as equity analysts usually do. Credit ratings don't do this: they simply describe the risks and strengths of the company, in an objective, structured way.

Early start

Just as in the debt market, companies could start to be rated before they go public. This would benefit investors in private funding rounds, an increasingly important process for innovative companies. But above all, it would mean there was public information out about the company well before the IPO.

Investors and issuers would not have to go through the awkward and offputting process of initiating transparency through IPO research in the stilted, private way it is done now.

And the equity market should also ask itself: is there actually something genuinely wrong with the IPO process, which could explain why so many investors don't want to get involved?

CAB Payments' share price has collapsed because of vulnerabilities in its business. In 2015 OW Bunker, the Danish shipping fuel supplier, went bust amid fraud allegations eight months after its Dkr3bn IPO.

There are many other examples. If rating agencies had been inspecting and grading these companies for a year or two before their IPOs, would they have picked up the problems? Not certainly, but they might.

A radical step to force equity research to become independent would be for regulators to ban investment banks from providing research ― just like they are banned from giving credit ratings. It would probably work, but is high-handed and risky. It might be necessary.

Better would be for this to evolve organically. The good thing is the market has an abundance of skilled equity researchers. For them to be organised differently, and present their work in a way that is much more successful at informing investors and giving them confidence to take risk on unfamiliar companies, will not be easy ― but the prize is surely worth having.