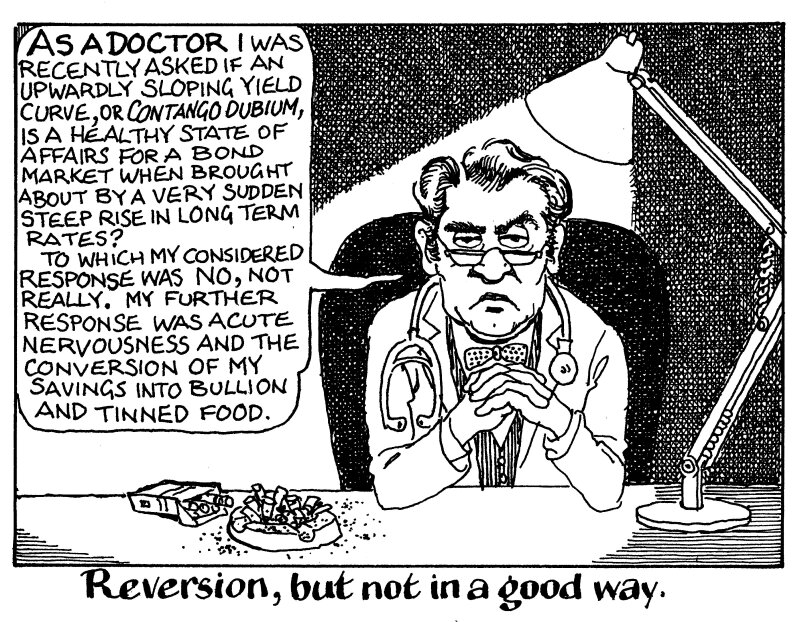

A reversion to a positive yield curve had long been thought necessary to drive a return of issuance at the long end of the covered bond market so that investors are paid, not penalised, for locking in long term risk.

It had been assumed that inflation and rates would fall quickly enough to reshape the yield curve so that longer term rates were higher than short dated ones. Indeed, this week the curve became less inverted but for reasons more likely to deter investors than encourage them.

With the US economy in rude health and the Federal Reserve set to raise rates and keep them there, the central bank’s ‘higher for longer’ mantra hit the long end of the euro yield curve.

After peaking at minus 85bp in early July, the spread between two and 10 year euro swap rates moved to minus 33bp by Thursday’s market close, the least negative it has been all year.

The fact that 14 borrowers have issued 10 year covered bond benchmarks this year at more inverted levels than this suggests it could be an opportune time for long dated issuance.

However, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The chief deterrent is outright rates volatility, this being a function of increasingly entrenched inflation and rates uncertainty.

As US Treasuries dived, 10 year Bunds were dragged along for the ride, causing yields to spike up over 3%, levels not seen since 2011.

Issuers looking for duration might be better off going to the senior market where wider spreads compensate investors for rates volatility and the inversion.

Either that, or they’ll have to consider paying a steep premium on a covered bond.

Compagnie de Financement Foncier’s decision to begin pricing its five year social debut at 40bp over mid-swaps with a concession of at least 10bp on Thursday illustrated extreme caution.

It may be a while yet before covered bond issuers can lock in some long dated funding.