It was all going so well. The UK government launched its green Gilt programme two years ago this week, with the biggest ever sovereign green bond. The £10bn deal won the most orders and largest book ever for a syndicated Gilt.

The second deal for £6.1bn was, at 32 years, the longest sovereign green bond. Another £9.9bn came in the 2022-23 financial year, with £10bn scheduled this year.

The DMO basked in the glow of bond market approval, mentioning in its first Green Financing Allocation Report that it had won accolades, including Most Impressive Government Green/SRI Bond Issuer in GlobalCapital’s Bond Awards.

Investors appeared to have bought into the government’s clarion call when launching the green Gilt programme that “The United Kingdom is committed to leading global efforts to combat climate change”. By buying the green Gilts, they could help it on its way.

About-turn

This week, prime minister Rishi Sunak turned the UK from a green leader into a green ditherer.

In a seemingly unprovoked attempt to repair the government’s dwindling popularity, Sunak announced retreats on several important policies to decarbonise the economy. He scrapped requirements to insulate homes and pushed back bans on selling new petrol and diesel cars — and on installing new gas boilers — from 2030 to 2035.

Companies bringing to market the greener technologies the UK should be phasing in, such as electric vehicles and heat pumps, were incensed at this moving of the goalposts. So were investors trying to manage portfolios to decarbonisation pathways.

Possibly more damaging than these policy changes was the misleading cloud of rhetoric with which Sunak swathed them. He implied that governments previously (which he served in and led) had not “had the courage to look people in the eye and explain what’s really involved”, that they had acted anti-democratically, and that his new weaker policies constituted “a wholly new kind of politics”.

He called for “a better, more honest debate about how we secure the country’s long-term interest”. But before having that debate, he unilaterally changed the policies at stake.

“We’ll never force anyone to rip out their existing boiler and replace it with a heat pump,” Sunak boasted — though his existing policy already said that “No one will be forced to remove their existing boilers”.

Setting back progress

The PM’s real purpose is a dangerous one: to destroy the political consensus that has so far shielded the UK’s gentle steps towards its net zero targets. Green issues are now a battleground that dinosaurs can exploit by presenting rapid decarbonisation as a threat to voters’ freedom and prosperity.

There was good in Sunak’s speech too: he reaffirmed that the UK is still committed to net zero, made a boiler upgrade grant more generous and lifted the ban on onshore wind farms.

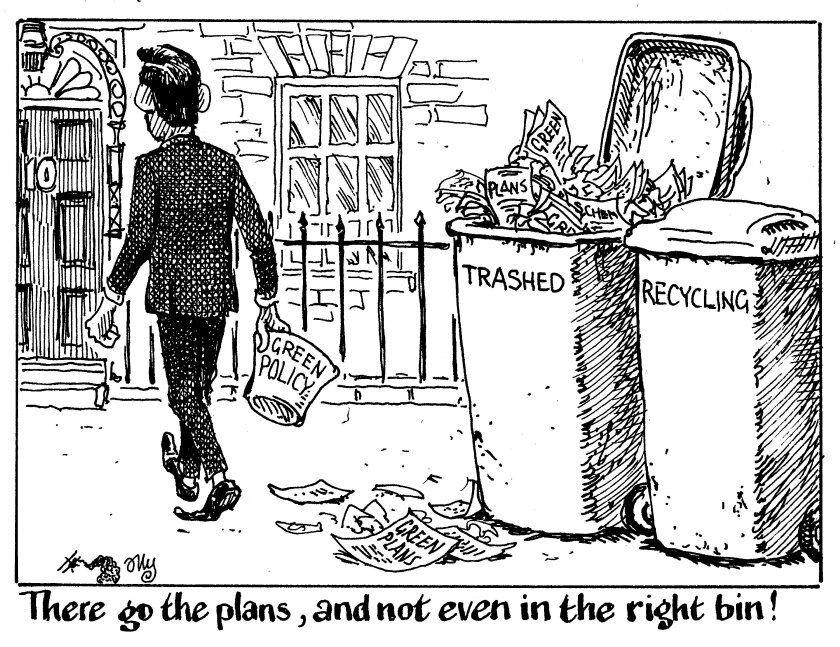

But the overwhelming effect is to trash the government’s own carefully worked out plans and arguments for greening the economy at a moderate, but still stretching, pace.

Unreliable words

Investors need not fear that the administration will default on its promises to back green Gilts with sufficient green spending. The promises made in green bonds are easy to fulfil.

But the real point of the instrument is communication — the green glow of enthusiasm they generate among investors who want to support the issuer’s green purpose.

That is why almost every green financing framework begins with a long preamble about the issuer’s green strategy, how important it is and how strongly the organisation is committed to it.

The UK’s framework is an excellent example. It blazons the UK’s ambitious set of five-yearly carbon budgets, stretching out to 2040. It trumpets the 250,000 jobs it expects to be created in low carbon heating and energy efficiency. The UK’s first Green Financing Allocation Report underlines how transport contributes 27% of UK emissions, 91% of them from road vehicles.

Policies on all these issues were attacked in Sunak’s speech. What are investors to think now when they read the documents that underlie the green Gilts, and present the investment case for them?

Tied to a promise

Sunak has thrown away, not the bonds’ uses of proceeds, but the momentum and credibility that came with them. Investors will take the message: green bonds can come with a lot of pompous language, but don’t trust it.

In light of this experience, the unsung virtues of sovereign sustainability-linked bonds suddenly shine brighter. Chile and Uruguay are the only issuers so far, with targets linked to controlling their greenhouse gas emissions, protecting native forests and gender equality on company boards.

There may be arguments against these structures, but at least the governments that bring them are having a clear conservation with investors: “we will make this improvement, or pay a step-up coupon”.

Investors might do well to take that promise over a green glow.