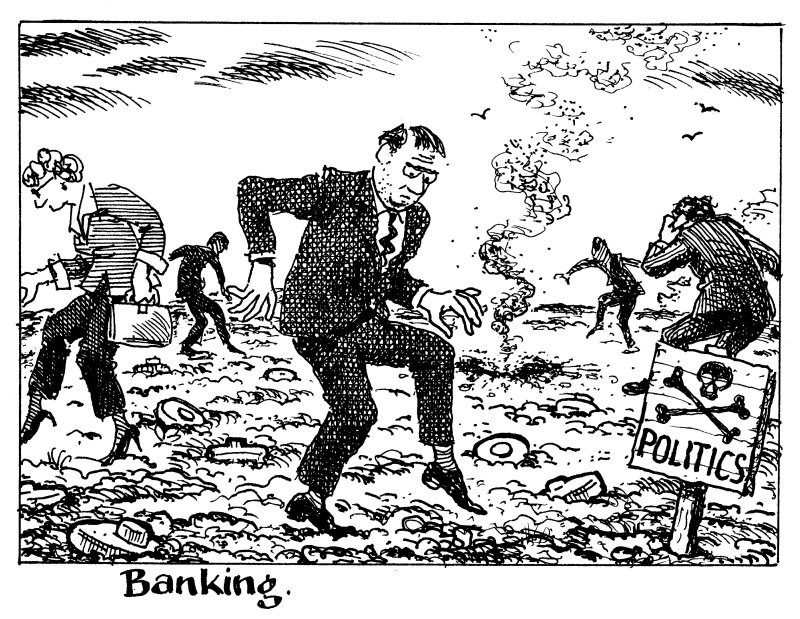

Banks are institutions mired in politics — and not just politics of the office variety. It is the price they pay for being of systemic importance, especially when that system bailed them out and is to thank for their very existence.

It has become a common observation that banks are now utilities. But they are so much more than that — they are political animals, although perhaps more akin to domestic pets than apex predators roaming the wild. Think Rottweiler on a leash rather than lion in the savanna.

That is why when they bare their teeth or go after a smaller creature — as NatWest did with Nigel Farage, the controversial political figure and now ex-customer of its private bank, Coutts — they can earn themselves a whack on the nose from their owner, rather than a tummy rub and a pat on the head.

In NatWest’s case, the rebuke came from its biggest shareholder, the UK government, which became so following the bank’s 2008 bailout when it was called Royal Bank of Scotland. The government felt moved this week to criticise the bank’s handling of the Farage fiasco, costing CEO Alison Rose her job and shareholders a near-5% hit to the value of their holdings as of Thursday evening.

And it’s not just NatWest. The charity Christian Aid dumped Barclays over its involvement in fossil fuel financing — an embarrassment for the UK lender, as GlobalCapital argued this week. Its share price was about 3.5% down since Monday as GlobalCapital went to press, though it is unlikely the charity snub explained much of the drop.

Bank management has a tough job, juggling reputation with shifting societal attitudes with the need to make money. There is always one constituency ready to give them a kicking, whichever choices they make, and CEOs come and go. But the vicissitudes of daily life, which manifest in share prices, do not give a good picture as to a bank’s long-term stability.

For that, the bond market offers a much more useful guide. It is notable that neither Barclays’ or NatWest’s bond prices moved very much after this week’s conniptions.

For a serious, long-term view of whether a bank is truly on the skids, the debt markets offer a much better glimpse of future health — just ask Credit Suisse’s AT1 holders.