Capital markets players are slapping each other on the back in relief this week, hailing the end of “the shortest banking crisis ever”.

The situation that began with Silicon Valley Bank collapsing on March 10 and took down Credit Suisse, one of Europe’s great banks, has been resolved, many feel. Regulators handled it well, Credit Suisse was an isolated case with longstanding problems of its own, and even the battered additional tier one capital market is licking its wounds.

This would be exactly the wrong message to take away from the last fortnight’s drama.

Once again, the world stared into the abyss of horror that is a banking crisis. The first shock is that it can come out of nowhere. Silicon Valley Bank was not a slow-building risk that everyone became increasingly worried about. They are not going to make the next Big Short about its demise. One day it was not an issue anyone was thinking about. The next, the whole global banking system was shaking.

It is flabbergasting that SVB could have failed in this way. The central problem that floored it was so basic that a child who had read the Ladybird book of banking could have seen it coming.

Banks are not meant to carry interest rate risk because — yes — interest rates can change. Holding a lot of unhedged fixed rate assets, financed with short term and floating rate liabilities is the one thing a bank can’t do.

That it was allowed to do so shows appalling laxness by US regulators. Donald Trump cannot bear all the blame — SVB may have been excused to a lower grade of regulation, but even a sub-$50bn bank should not have been allowed to behave like this.

It also shows remarkable folly by the US tech companies and funds that lavished deposits on SVB, in some cases storing all their money there.

This laziness produced one new feature in the SVB crisis: the crash was so swift, and required such drastic action by the authorities in guaranteeing all the deposits, precisely because of the concentrated nature of the depositors.

They showed a herd mentality, and would have been killed in a herd if they had been allowed to suffer the consequences of their mistakes, blighting the Californian economy.

Financial crises always include the unexpected, as otherwise they could not happen. Market participants must draw from SVB a reminder that the next crisis will come from somewhere they are not expecting.

And, as SVB showed once more, crises also always include both age-old sins and new ones.

Credit Suisse, many say, was a disaster waiting to happen. Its name had been besmirched umpteen times by scandals and errors.

But the wave of fear that washed away its foundations was still appalling because it was so irrational. Credit Suisse was unlucky enough to have to make an announcement about previous failures of controls — not even a new loss — during a week when markets were already queasy about bank risk because of SVB. That was enough. A self-fulfilling run on its securities began.

Credit Suisse had plenty of capital and liquidity — painstakingly checked, rechecked and redoubled by Swiss regulators. But none of it was enough — the market’s thirst for blood would not be slaked until it had been swallowed by UBS.

This week, the air has been full of additional tier one capital — were the regulators right to have zeroed Credit Suisse’s AT1 layer, while allowing some recovery for the equity?

As it happens, it looks like they were fully within their rights. The EU and UK central banks quickly reassured investors they would preserve the capital hierarchy if it happened on their watch.

But this is a sideshow. What the SVB and Credit Suisse crisis showed is that when fear takes hold about a bank, no capital structure or liquidity facility is going to be enough.

CS had been stress tested and deemed to have enough capital to cover its risks. It’s not that the stress test was wrong and it should have had 20% or 40% more capital. No amount of capital is enough if market participants no longer want to lend to a bank.

The millions of hours that have gone into carefully crafting measures of bank risk, and different layers of notes that can be bailed in or written down in various ways are all pious nonsense.

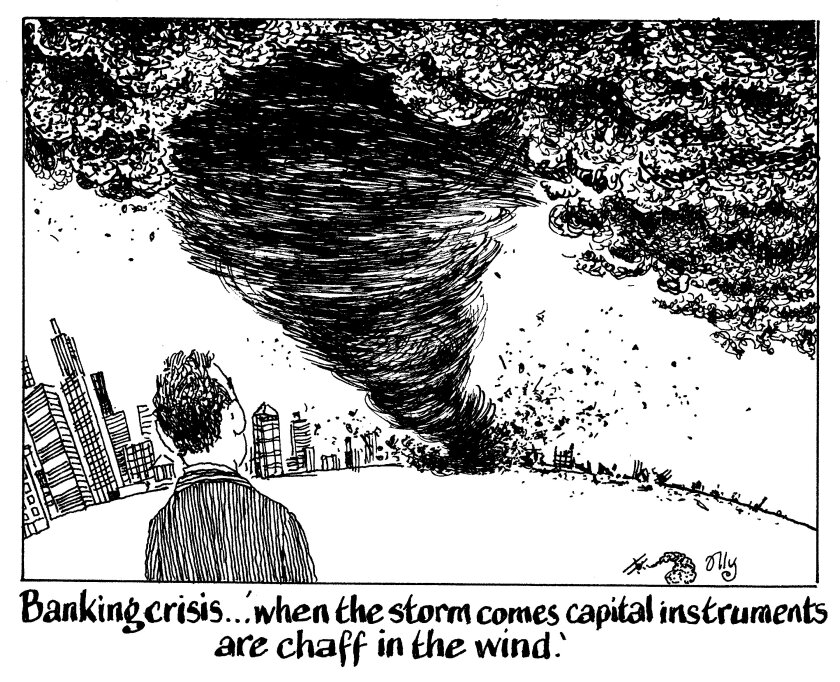

When the hurricane of banking panic comes, all these fine structures will be swept away. Do the AT1 investors relieved about the capital hierarchy really think that if the shares in a bank are wiped out, they are going to be kept whole? Does anyone really believe a struggling bank will be able to bail in its tier two or senior non-preferred and survive?

When the storm comes, it is savage. The authorities take control and try to save the ship, doling out losses as they see fit. You’re a bit safer higher up the capital structure. But banks are inherently unstable and rely on confidence. And that can vanish overnight.