The UK returned to the bond market on Tuesday with a new 30 year benchmark. The deal bore many of the hallmarks of one of the Debt Management Office’s now customary slick syndications, but the UK is an issuer that still bears the scars of last autumn.

With the Bank of England expected to raise rates by 50bp next week, record high borrowing in December and net Gilt issuance projected to double over the coming fiscal year, the UK nonetheless made a successful test of investor appetite for duration.

So far, so normal. But although investors piled more than £68bn of orders into the book, the issuer had to add more premium than usual to lure them into the £6bn 3.75% October 2053s.

And the feeling in the market this week is that the UK will keep having to pay an elevated premium for some time to come.

Inflation remains high and while sterling has recovered most of the ground it lost against the dollar in the aftermath of the infamous and swiftly reversed mini-budget that short-lived prime minister Liz Truss and her even shorter-lived chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng cooked up last September, investors are still demanding a bigger premium on their new Gilt purchases after that unedifying debacle — the so-called ‘moron premium’.

The pair’s goal of funding billions in energy subsidies and growth plans through the bond market has done lasting damage to the UK’s reputation as a borrower.

In a note published the day before this week’s syndication, UBS argued: “We think it will take a lot more than a new prime minister, a few positive data points, and a 50bp hike to get international investors to warm to sterling.”

The UK, of course, enjoys a large domestic investor base of institutions that have a natural requirement for long-dated Gilts. Even so, people on the deal did not care to name the extra premium the UK paid this week. Sources in the market put it at 3bp-4bp.

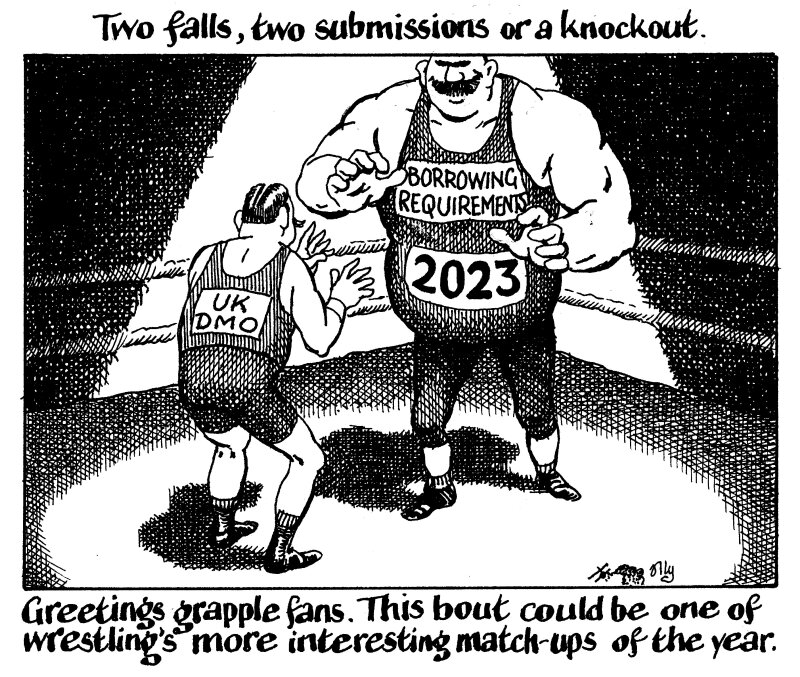

A banker close to the transaction said the Gilt syndication had been a strong trade but he also emphasised just how much borrowing the UK needs to do this year. Analysts at NatWest said the UK’s funding needs were “eye-wateringly high”.

The DMO has handled big borrowing requirements before. But the extra premium it is now paying — and the burden that places on government spending — is the true legacy of Trussonomics.