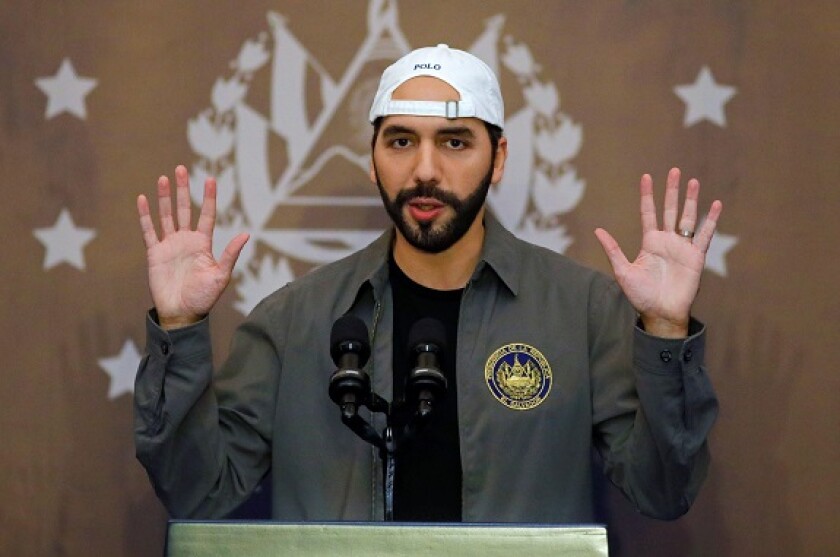

The Latin American sovereigns that have sought to take advantage of depressed bond prices might argue that they have obtained the desired results. After reacting angrily to suggestions that his government was at risk of defaulting, El Salvador’s president Nayib Bukele’s decision to tender for the sovereign’s 2023s and 2025s triggered a rally in both bonds last year. Indeed, the government repaid the 2023s in full on Monday having earlier repurchased a portion of the notes at a small discount to par.

Argentina’s bonds, too, outperformed after finance minister Sergio Massa said last week he would buy back $1bn of the sovereign’s dollar 2029s and 2030s — although investors are still unsure as to his logic, given the country’s low level of international reserves, and the low coupons on these bonds.

In the nearby Caribbean, the Bahamas’ sovereign curve enjoyed a strong rally after the central bank temporarily waived a tax on local institution’s buying the government’s international bonds — leading to more than $200m of onshore purchases in the bonds. EM portfolio managers following the credit suspect the government itself was behind at least some of the buying.

These are — at least in the case of El Salvador and Argentina — designed to be ways for governments with unorthodox economic policies to polish their pro-market credentials. The transactions not only suggest that they do care about repaying debt, but indicate that the cash-squeezed governments are perhaps not as desperate as they might appear and have the luxury of making apparently astute strategic choices about what they do with their money.

But all three rallies have commonalities: they were one-offs, likely to have little long-lasting impact on bond yields, and did not put any of the aforementioned countries back on the road to market access.

Argentina’s dollar bonds still trade at a cash price in the low 30s, while El Salvador’s 10 year debt yields almost 20% — despite the recent surge in appetite across credit markets.

It is worth remembering that the prices of all these sovereigns’ bonds are so low not only because the sharp increase in US interest rates sent the value of all fixed income instruments plunging last year. All three are also serious default candidates, facing chronic fiscal issues.

Bond buy-backs cannot mask these issues. Argentina’s problems line in constant monetary financing of a large fiscal deficit and extraordinarily high inflation, for example. These tender offers have done nothing to assuage concerns fears about some of Bukele’s ability and desire to tackle El Salvador’s budget deficits while he moves the country away from traditional sources of funding, such as the IMF.

Sure, if these governments believe that bond investors are wrong and are somehow failing to see what great credits they are, then the buy-backs make perfect sense. In this case they would be taking advantage of a distortion in the market, and when economies start to perform and bonds enjoy a sustained rally, governments will feel very smart for having slashed debt on the cheap.

This is not likely to be the case in any of these countries. Long-term problems require long-term fixes, and neither of the governments in power in Argentina or El Salvador have appeared willing to undertake them.

What’s potentially worse is that these governments are throwing away precious cash at bondholders: investors in El Salvador’s 2025s saw their holdings jump from below 30 cents on the dollar to 50 in a matter of days when Bukele revealed the buy-back. They could sell them at 62 in the December tender.

In a terrible year for EM investors, Bukele will have at least made the bondholders that timed the market right happy. But bond buy-backs have had little to no impact on the long-term debt sustainability of these countries.