Last week a seminal event occurred in the history of central banks’ engagement with climate change.

In a speech in Stockholm, Isabel Schnabel, the European Central Bank executive board member who acts as its authorised thought leader on climate action, gave perhaps the most forthright argument by a central banker yet that “all” a central bank’s policies should be “aligned with the objectives of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius”.

The argument was cleverly tied in with current monetary policy. Higher interest rates were necessary to control inflation, Schnabel emphasised — partly because inflation would make it harder to achieve the green transition.

But high rates risked delaying the transition, because renewable energy is more vulnerable than fossil fuel power to higher interest rates, since more of its cost is for the initial capital investment. The levelised cost of electricity from a gas plant would barely change if discount rates doubled, Schnabel argued, while for offshore wind it would rise by 45%.

Governments should step up to the plate and do their part, starting by removing harmful fossil fuel subsidies. But central banks would need to put their shoulders to the wheel, too.

Ultimately, she said, it was essential to take seriously the concern that “unless greenhouse gas emissions are cut rapidly, our economies will remain exposed to the risks of ‘climateflation’ and ‘fossilflation’ — that is, persistent inflationary pressures associated with more frequent natural disasters and a continued dependency on gas, oil and coal.”

As well as price stability, the ECB’s secondary mandate is to support the general economic policies of the EU. They include ‘Fit for 55’ — cutting carbon emissions 55% from 1990 levels by 2030.

Central banks, in other words, cannot be bystanders in the fight against climate change — they must be combatants.

Tooling up

Much of the intellectual armoury for this battle has been forged in the past five years since the founding of the Central Banks’ and Supervisors’ Network on Greening the Financial System (NGFS).

Perhaps the central banks’ greatest power is as supervisors of the banking and financial systems. They are using it to compel banks and insurance companies to calculate and manage their climate risks.

But green finance enthusiasts have always gazed longingly at a more visible prize — the central banks’ vast balance sheets, bloated by years of quantitative easing.

The Eurosystem’s consolidated balance sheet was €8.6tr as of December 2021, including €2.2tr of loans to eurozone banks and €4.9tr of euro bonds issued by eurozone entities, mostly owned for QE purposes.

For as long as most capital market specialists can remember, central bank firepower has been the answer to almost every macro problem facing the markets. So why not climate change?

If that vast money pile could be deployed to green the economy, could it not work wonders?

Bold words

Having a dream does not make it reality. The ECB is governed by law and needs to float on the waves of public consent. For both reasons it cannot veer too abruptly in a new direction, especially if this could be seen as disadvantaging some member states.

For all that, under Christine Lagarde’s presidency the Bank has become increasingly radical in its climate change stance, moving from an also-ran to leader among its peers.

Schnabel now forcefully advocates aligning all the ECB’s bond portfolios, including those held for monetary policy and as collateral for repo lending to banks, with the Paris Agreement — including public sector bonds.

Doing that, she admits, will be difficult. Above all, the ECB has to allocate money among member governments’ bonds fairly, according to its capital key. That means there is no scope for preferring the bonds of greener countries — which is probably lucky, as it would be politically explosive.

Despite that, Schnabel insists greening government bond holdings is desirable in principle. Workarounds at the edges could include buying more green bonds. Sovereign green bonds could be preferred to ordinary bonds where available and some govvie holdings could be replaced with supranational and agency bonds, where green instruments are more common.

In the financial institution sector, the ECB holds covered bonds and asset-backed securities. Schnabel is determined to apply climate criteria to these, so that the Bank could prefer the better performers, but it has not yet worked out a methodology.

Another big chunk of bank exposure is through repo lending, where Schnabel called for “a systematic greening of the ECB’s collateral framework”. When policy goes expansionary again, there could be a green version of the Targeted Longer Term Refinancing Operation (TLTRO).

Losing firepower

Public sector and financial bonds are big swathes of the balance sheet. But the low-hanging fruit is corporate bonds — €344bn bought under the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme and €44bn under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme.

Here, the ECB is much further along in sorting the green from the grey.

Since October 1, the ECB has been applying a climate tilt to its corporate bond purchases. It has developed a three part scoring system. Companies get credit for having lower greenhouse gas emissions — relative to sector peers and the corporate market as a whole; for having more ambitious decarbonisation targets; and for better climate disclosures.

The trouble is, the ECB is not buying many bonds. Since June it has been keeping the portfolios at a constant size by reinvesting maturing principal. For the CSPP holdings that is expected to be €31bn this year, an average of €2.6bn a month, fluctuating between €1bn and €4.2bn.

As a result, the once all-important ECB has faded from view as a corporate bond investor. “They might buy, they might not,” said a corporate debt capital markets banker in Frankfurt. “They’re just another potential investor.”

The ECB’s current appetite is too small for him to have noticed any marked climate preference.

Soon, the ECB will cut back on reinvestment as it tightens monetary policy further. The less it buys, the slower it will be able to green its portfolio. If reinvestment stops, it will become a passive holder — its portfolio would only become greener if the companies themselves decide to, and it would have no leverage over them.

The ECB must not accept this, Schnabel said. It is not official policy yet, but she set out how the Bank would switch to active greening of its portfolio, using its climate scorecard to sell worse performers and buy better ones.

Corporate whale

The news has taken a while to filter through to corporate bond and sustainable finance bankers. But the implications could be far-reaching.

“I know it’s the right political thing to say, but it’s a bit dangerous,” said the head of debt capital markets at a bank in southern Europe. “It’s forcing everybody to go in that direction.”

He foresaw the market focus changing from working out a greenium price benefit for green issuers to the opposite: “what you need to pay if you issue black and not green”.

The banker in Frankfurt said: “To me, this throws out a lot of questions. If their mandate is to maintain orderly markets, how do they justify it? How do they do it? If you know the ECB is going to be selling tobacco bonds, oil and gas, metals and mining companies, chemical companies, don’t you move the market materially?”

This is exactly what analysts at the Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute are hoping will happen. The Stockholm think tank which studies climate action in bond markets is delighted with the ECB’s change of direction.

It has analysed the CSPP portfolio based on its calculation that the ECB holds an average 27% of each eligible bond — which amounts to 9% of the total debt stock of eligible companies — and estimates of each company’s carbon emissions.

The AFII estimates the ECB could remove the great majority of the emissions in its portfolio, just by selling the bonds of the 51 carbon-heaviest issuers. These range from Shell, which the AFII estimates emits 677m tonnes of CO2 equivalent a year, to Ryanair with 9m.

“We feel confident that a majority of the reshifting of the CSPP on a climate basis would happen within this set of 51 names,” the Institute said.

Clues in Powerpoint

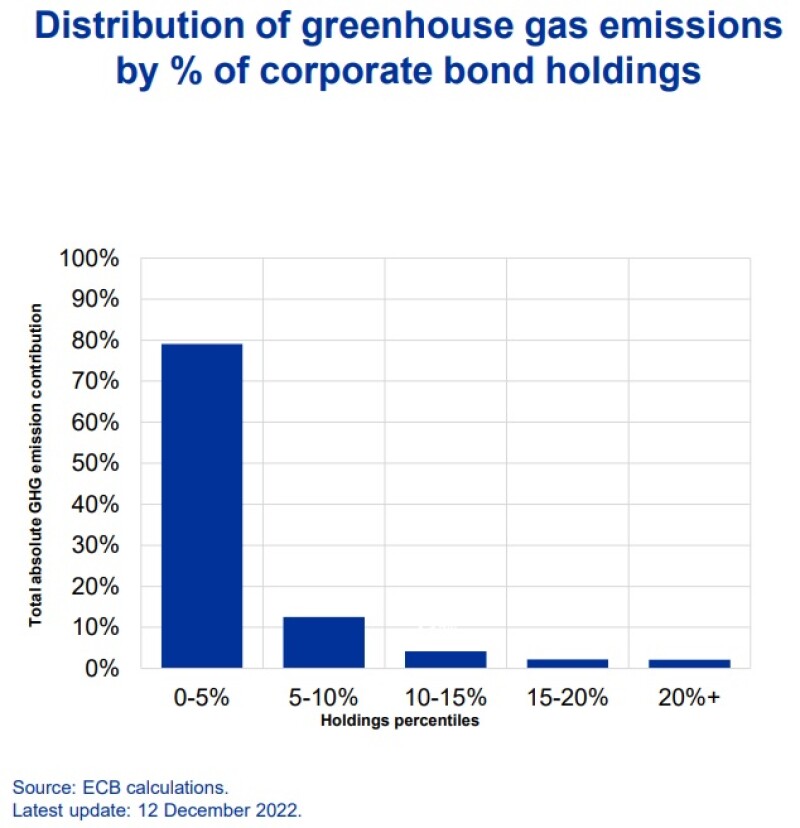

A clue that could support that view appears in one of Schnabel’s slides. It showed that about 79% of the emissions were concentrated in 5% of the bonds, and 91% in 10% of them (see reproduction of Schnabel's chart below).

The trouble is, no one knows what the ECB will do. Although it is generally quite a transparent organisation, it has so far, through perhaps understandable caution about inflaming commercial sensitivities, not revealed much about its corporate bond climate tilt policy.

Market participants have a general idea how companies are classified. They do not know what the specific scores for each company are.

Nor do they know how hard the ECB applies the tilt. For example, does a company in the best bracket get 120% of the baseline allocation, or 150%, or 200%? Does one in the worst layer get 80%, 50% or nothing? Market participants have no idea.

Up to now they have not seemed particularly curious about it, because in the past three months the ECB has been a shadow of its former self in the corporate bond market.

But if it switches to a more aggressive policy of churning the portfolio, issuers, banks, traders and investors will very much want to know.

How fast is faster?

They will also be clamouring to ask how fast the ECB is going to turn over its portfolio. Again, there may be a clue in Schnabel’s slides.

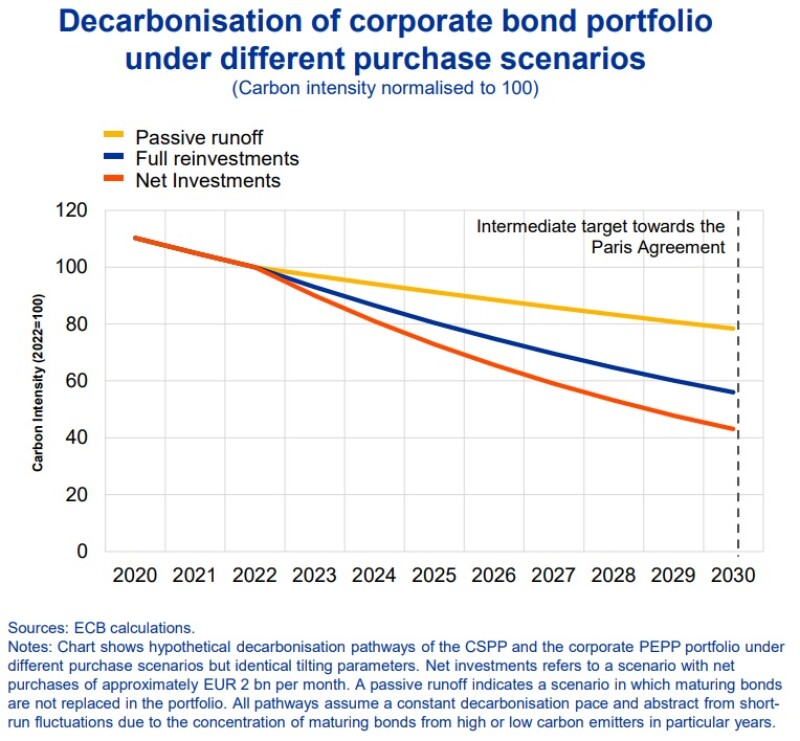

Another graph shows that, assuming companies themselves make efforts to decarbonise, the carbon intensity of the ECB’s corporate bonds would fall 42% from 2020 levels by 2030, if the ECB was fully reinvesting maturing principal. If the portfolio is allowed to run off passively, carbon intensity will only fall 20%.

But if the ECB makes net investments of €2bn a month, the metric would fall about 58%. (See reproduction of Schnabel's chart below.)

Why did Schnabel choose €2bn a month? It could be a hint. It certainly shows that at that pace, the ECB would decarbonise substantially.

Getting close to zero carbon intensity by 2030 is unlikely, because Schnabel also said the ECB did not want to disinvest completely from even some of the high emitters, as long as they were driving the transition to low carbon. So the 58% cut, and hence €2bn a month, looks credible.

Of course, the ECB may want to go for steeper cuts in carbon early on.

But if the path is to be smooth, as in Schnabel’s graph, that has several implications. First, €2bn a month may be much less than alarmists feared.

The figure can be assumed to require also reinvestments of principal, which this year will average €2.6bn a month.

If the ECB moves to a policy of no reinvestment, so the portfolio has to decline as it matures, this would mean the ECB having to sell €4.6bn of bonds a month, less any redemptions of bonds it wanted to sell anyway, and buy the same quantity, in primary or secondary markets. Assuming 21 working days a month and without counting redemptions, that is €220m a day.

Up to now, under the CSPP, the ECB has tended to spend about 75% of its money in the secondary market, the rest in primary.

The average daily trading volume of European corporate bonds was €13bn in the first half of last year, according to the AFII, although the average for any single bond was only €1m.

If the ECB wants to make its market impact gentle and smooth, it probably can.

Get explicit

How should the ECB act, to generate the most benefit for the climate, while operating as a responsible market participant?

It is important to consider how the ECB can actually influence behaviour on the ground.

Selling all its high emitting bonds might drastically reduce the carbon emissions embedded in the ECB’s portfolio. It would remove a public sector subsidy to harmful, polluting industries like oil, gas and mining. It would raise the cost of capital for those industries by a few basis points. And it would make the ECB’s hands look clean.

But it would not stop people burning coal, oil and gas or using steel. And it would lay the ECB open to accusations of climate extremism.

More effective would be to use its climate tilt very explicitly to lean against the high emitters, without divesting from them altogether.

Whatever economic purists might think, tweaking the economic levers to change cost of capital, on its own, is unlikely to make much difference. What does influence people is actions and words together. Meaning, backed up by money.

The ECB should make its climate scores for companies public. This might make the hairs on central bankers’ necks rise in fright. But they should get over it.

Big Oil might not like to be seen in the climate doghouse — but the weighted scoring system means the more ambitiously decarbonising oil companies might do quite well. And, whether it’s public or not, the ECB is already using those scores. Laggards would have little justification for trying to block publication.

Then, go public on the mechanism of the tilt. How much, exactly, does the ECB love green companies more than grey? There is no reason, other than innate caution, not to reveal this.

For the portfolio reshuffling, make the criteria clear. There are all kinds of creative ways they could be structured. As a very basic example: in year 1, the bottom 20% for each of total emissions, emissions compared with peers, sloth in decarbonisation and climate disclosures get a 20% weighting cut. In year 2, add a 10% weighting cut for those in the second worst quintile.

The criteria can be structured to strongly incentivise improvement and penalise backsliding, versus sector peers as well as industry as a whole. The best designed policy would keep both a carrot and a stick hanging over every issuer.

Get a grip

In the financial sector, ultimately metrics should be developed to enable carbon assessments of issuers. Sophisticated banks are supposed to be working out their carbon footprints anyway — there is no reason why climate tilts for covered bonds should be tied to the specific mortgages in the cover pool, though this could be done too.

Force banks to produce the data, then apply carrot and stick to them, too, to green their balance sheets and securities underwriting.

In the public sector, green bonds may be the only viable tool in the short term. But cementing in a greenium would do considerable good. According to the ECB, Germany’s 2025 green bond already trades about 13bp tighter than its non-green twin — a huge gap for Europe’s most elite issuer.

Green bond bankers’ fears that pronounced greeniums would put off investors and be self-defeating have proved unfounded.

Sustainability enthusiasts should not kid themselves. A slim greenium like this is insignificant to determining whether new green projects such as wind farms or solar parks go ahead. In real world industry, project viability is measured in percentage points, not basis points.

But there is one sector where even 5bp or 10bp makes a material difference — mortgages. Homebuyers would be willing to make sustainability improvements if they could save even a few 10s of euros a month. If the ECB could apply tilts that supported the emergence of a consistent price benefit for refinancing green mortgages, it could be one of the most effective policy levers for climate yet tried.

The ECB’s policy shift contains many exciting possibilities. It should be brave — especially about transparency — and get a move on.

And buried in Schnabel’s speech was another gem. In coming out strongly for buying green bonds to drive the economy towards climate health, she quietly skirted round the central bankers’ hang-up about changing risk capital weightings for green assets.

The orthodoxy is these cannot be lowered until green assets can be proved to be lower risk. This is the equivalent of saying ‘I’ll lend you the money if you can prove you don’t need it.’

And by the time there is proof it may be too late.

If the ECB itself is willing to use its capital to preferentially buy green bonds to aid the climate and hence preserve price stability, why shouldn’t banks do this too?