Emerging market lenders have stood by their Turkish bank clients despite deepening economic woe in the country. Soaring prices and shrinking syndicates this autumn show some international banks are rowing back from their Turkish exposure, but lenders should have seen this coming earlier.

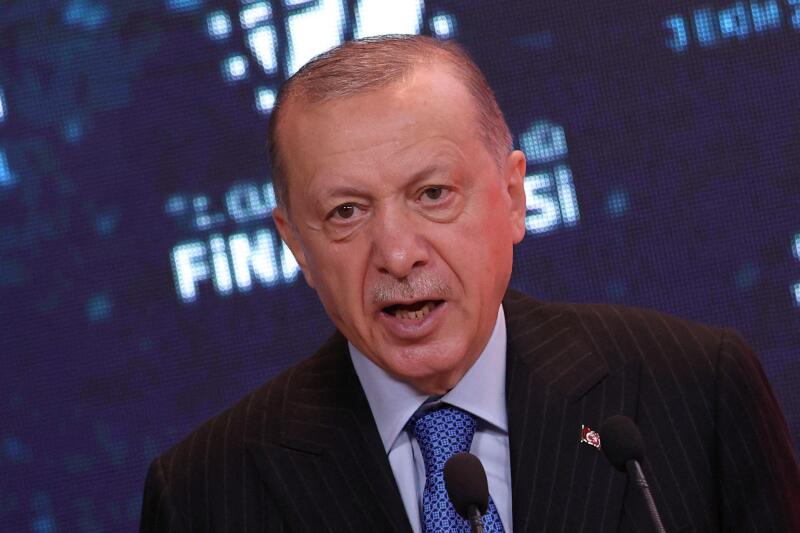

A year ago, president Recep Tayyip Erdogan forced the central bank to cut interest rates to stem inflation. Meddling with central bank independence is never popular with investors but forcing it into unorthodox policy such as that is even worse. Neither is declaring an "economic war of independence", as Erdogan did.

The lira has since slid, inflation has soared and many foreign investors have run for the hills.

Last November GlobalCapital warned international lenders that they should stop and think about their lending to clients in Turkey, and that the latest crisis there was different to those in the past.

But even a few months later they remained bullish, telling GlobalCapital that although prices may rise a little, international lenders would not be turning their backs on Turkish bank clients. Turkey has been through sticky patches before, they said, and lending has rumbled on.

This autumn’s refinancing round may be the turning point, however. Akbank and Vakifbank have both refinanced loans at prices far higher than in the spring or last autumn. But perhaps more importantly, the number of banks rolling into new loans has dropped.

So some international lenders are turning their backs, but not all. This proves that money and risk trumps relationships in the end, no matter how important those lender-client ties are in the loan market. Vakifbank expects the average rollover rate for refinancings in October and November to be 70%.

Surely this was inevitable. Erdogan has doubled down on unorthodox policy over the last year, exacerbating the country's economic woes with decisions long criticised in international markets.

There are further storm clouds building for those sticking by Turkish clients. Next year comes an election, and there is no guarantee Erdogan will relinquish power in the event of defeat nor deviate from his economic plan.

As a global recession looms, threatening international lenders with a whole host of problems in an array of other markets, the prospects do not look good for Turkish borrowers. Governments toying with contrary economic policy should take note that they cannot rely on lending relationships for their institutions indefinitely.