It makes you wonder if Kwasi Kwarteng is secretly an anarchist.

He takes the second most important job in the UK government, as chancellor of the exchequer, and then almost immediately tells the public he wants to make investment bankers richer.

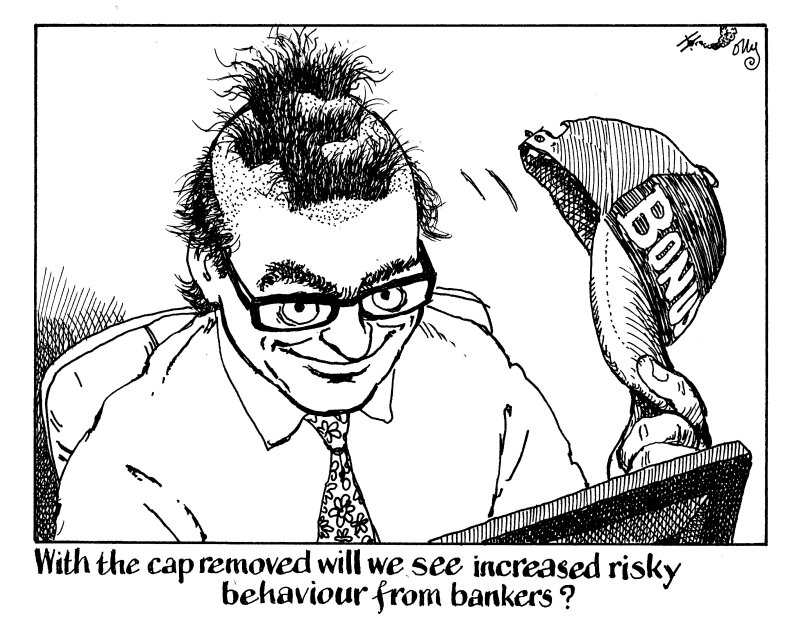

By scrapping the legal cap on their bonuses, in the middle of a cost of living crisis, Kwarteng is risking an all-out rebellion.

He followed up the bonus plan with promises to squeeze conditions for poor workers receiving Universal Credit benefits. Meanwhile, teachers report that they are handing out food and clothes to students; and nurses say they will have to choose between buying food or fuel.

It is hard to imagine a strategy behind this that does not involve pitchforks, torches and an angry mob.

Furthermore, his timing in suggesting a removal of the cap on banker bonuses is terrible in a second way: the step is overdue.

After the financial crisis in 2008, the European Union introduced the restriction to prevent banks rewarding managers for excessive risk-taking.

Since 2014, bonuses have been capped at 100% of a banker’s fixed salary. With shareholder approval, this limit can be increased to 200%. Most UK banks have done this.

The cap was a good idea. The problem is, we know it doesn’t work, and we have known for years.

The International Monetary Fund found in 2016 that the effect of bonus caps was offset if banks increased fixed pay. That is exactly what happened in the UK.

There are more effective measures: the IMF recommended in its Global Financial Stability Report in 2014 that banks should link bonuses to their financial health.

They could pay bankers partly in long term bonds, to discourage risky behaviour when a bank is financially weak.

Clawback provisions that force bankers to return bonuses if their decisions cause damage in later years have also proved helpful, as long as they are clearly linked to risk assessments.

No government should cling to a useless pay restriction just because removing it would upset some people who aren’t even affected by it.

With slightly cleverer communication, Kwarteng might even be able to convince nurses and teachers that the extra income tax revenue the measure could bring in from the private sector would help the state support everyone.

But removing the cap is not exactly a matter of painful urgency. Financial deal volumes have plunged this year and the economic outlook is bleak. Bonuses are unlikely to burst anyone's wallet this year anyway.

In times of poor business and low fees, removing the cap might mean bankers moving from a low bonus and high pay to a low bonus and low pay.

Truss and Kwarteng need to keep the British people fed and warm through the winter if they don’t want them to eat the rich and burn down the castle. If they can do those things first, then by all means, do away with this ridiculous restriction.