Listing venues from London to New York and Hong Kong are falling over themselves to attract hot, young companies in need of cash.

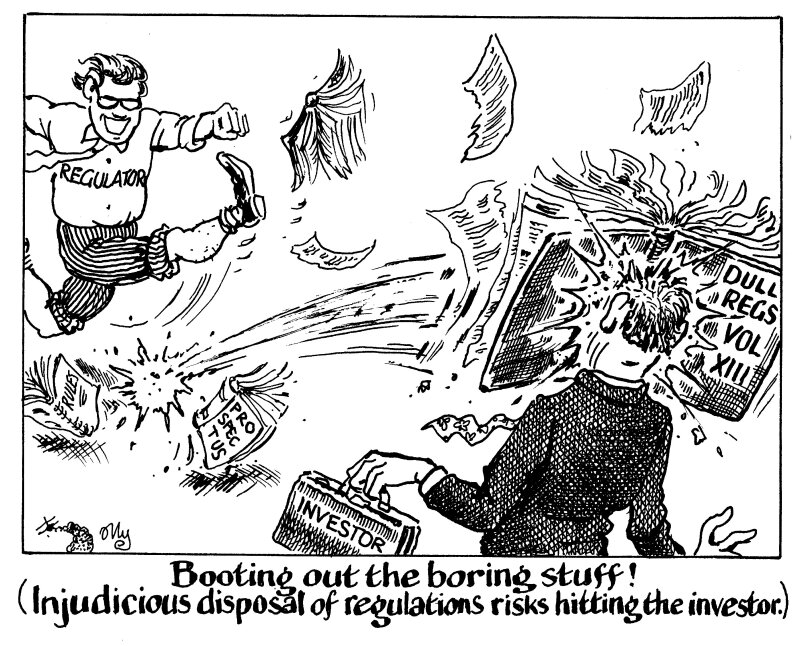

As listing numbers dwindle and competition between the bourses intensifies, especially over tech companies, regulators across the globe have come up with the same idea: that regulation is the problem. To a man with a hammer, every problem is a nail, as the saying goes.

Forcing companies to make three years of revenue disclosures ahead of an initial public offering? Inhumane! Filing a prospectus? Cumbersome! Redundant! Boring!

Or, as one capital markets lawyer put it: “Not even the investors read it.”

Of course, it would be a shame if bureaucracy was all that prevented a company from going public — and it is questionable whether every prospectus needs to spell out basic legal details that any serious investor should be aware of anyway.

In a market as volatile as this year’s, every day that a deal is in the market matters — and removing regulatory clutter can speed deal execution.

But in a mad rush to offer growth companies the easiest and fastest way to public capital, it is easy to forget the main purpose of regulation: to protect investors and to make sure they have a fair chance to know what they are buying.

If they cannot rely on thorough disclosures and transparent information, they could lose their appetite for growth companies faster than an equity salesperson can say “sector rotation”.

A market full of the illiquid stocks of companies that were not ready to come to market — or that burned everyone who bought the shares when they did — benefits no one and undermines the integrity of the market.

It is a difficult balance to strike. But a market that becomes a minefield is no place to put money at all.