No bank has put as much effort and money into building itself a reputation for sustainability as HSBC. No bank has had that reputation shredded as quickly as HSBC’s was when Stuart Kirk got up to speak on May 19.

The global head of responsible investment at HSBC Asset Management presented at a Financial Times Moral Money conference on ‘Why investors need not worry about climate risk’.

Kirk hinted at his intentions straight away by saying his beard was “my one sop to responsible investing”. He then laid into the environmental, social and governance investing industry, landing punches on many targets — including “nut jobs” who worry that the human race is doomed.

Kirk made a series of complex points, so his argument is hard to summarise quickly, but in essence he contended that although climate change is real, its actual effects on financial assets will be slight. Central bank climate stress tests had had to be cooked to produce scary enough results, he claimed, by introducing arbitrary sudden recessions and interest rate shocks.

Investors should therefore ignore long-term risks from the climate and concentrate on making money out of the transition and investing more in adaptation.

The backlash in public opinion was immediate and raucous. The CEOs of HSBC AM and the group swiftly distanced themselves from Kirk’s words, and he has been suspended from his job.

Pillorying and cancelling people for speaking their minds is not GlobalCapital’s style. Kirk may have been gravely wrong in much he said, but he appeared to speak honestly, and at some risk to himself — though it is unclear how many of the consequences he foresaw.

The episode calls for two things.

However much critics deride Kirk, some of his points struck chords with many listeners, inside and outside the asset management industry. Some of the things he said may have contained truth, such as criticising the mounds of tedious reporting and box-ticking that some ESG regulations require.

Like it or not, his speech was a trenchant and eloquent attack on ESG and climate risk awareness, which is likely to be rewatched for years to come.

The responsible investing industry needs to respond. It must examine his points in detail and develop refutations that are detailed and convincing.

This echoes the UK’s debate about Brexit before the 2016 referendum. ESG, like the European Union, is high-minded, fiddly, sometimes boring, disagreeable and imperfect. Bashing it is much easier than constructing a comprehensive defence.

But it must be defended. The sharpest irony of Kirk’s speech was his own job title. How someone with his views could have been picked last year as head of responsible investments was startling. What does Kirk understand “responsible” to mean, since he scoffed at banks considering risks longer than the six year average life of their loan books?

Much more importantly, what does the industry take “responsible” to mean?

Kirk dismissed attempts at ESG that get in the way of making money — and fears of future risks that are hard to prove today.

The probability of widespread crop failures two, five or 15 years hence as the climate heats certainly is hard to quantify. So are the methane emissions pouring out of warming tundra and oceans. So is the chance that deforestation tips the Amazon rainforest past a point of no return and it becomes a dry savanna.

Being responsible is precisely to recognise that some risks to human life and the natural world are so serious that it is worth putting other considerations before making money.

The second response needed to Kirk is by HSBC.

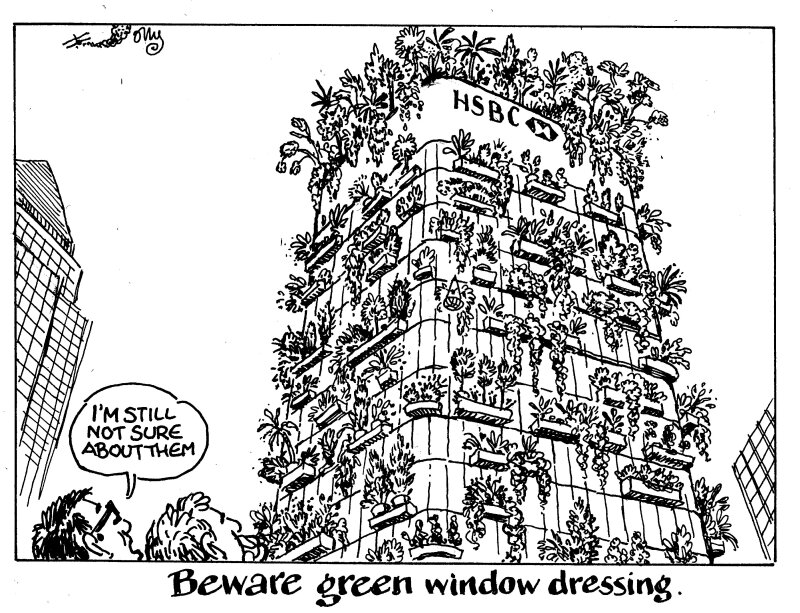

Critics were quick to pounce and say Kirk’s words revealed the true attitudes underneath its green veneer.

However unfair that is to thousands of HSBC employees genuinely concerned about climate and ESG and working on solutions, no amount of adverts at airports will now mend its image.

The bank is also facing a highly embarrassing investigation by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority into claims that its marketing constitutes greenwashing, in light of its continued financing of fossil fuel companies.

Partly at the urging of green-minded shareholders and NGOs, HSBC has declared a net zero emissions ambition, and has begun the work needed to cut its fossil financing. So far, this is still at the stage of crafting targets and metrics.

What HSBC urgently needs is to show results — actual figures that prove it is ceasing to finance fossil fuel expansion and reducing support for the fossil economy altogether. Cutting off some high profile clients would help.

The reaction against HSBC has been hard and crude. It can only hit back with hard, crude, green numbers.