With the price of Bitcoin down 50% in six months, the Terra stablecoin collapsing and Tether coming untethered from its official value of $1, last week was an awkward time to announce a sustainable investment that aims to make cryptocurrency mining “truly green”.

But that was exactly what Spring Lane Capital, the specialist private equity firm based in Boston and Montreal, did by revealing its $35m investment in Soluna, a company with a novel approach to the huge energy needs of the burgeoning crypto economy.

The deal raises the question of how large financial institutions can adequately square their interest in cryptocurrencies with their net zero emissions pledges.

Blockchain technologies, on which cryptocurrencies and many other applications are based, are many times more energy-intensive than conventional computing, since they require messages including transactions to be distributed to and validated by all participants in the network.

Some blockchains such as Bitcoin and Ethereum rely for validation on ‘proof of work’, meaning unending decryption work known as ‘mining’.

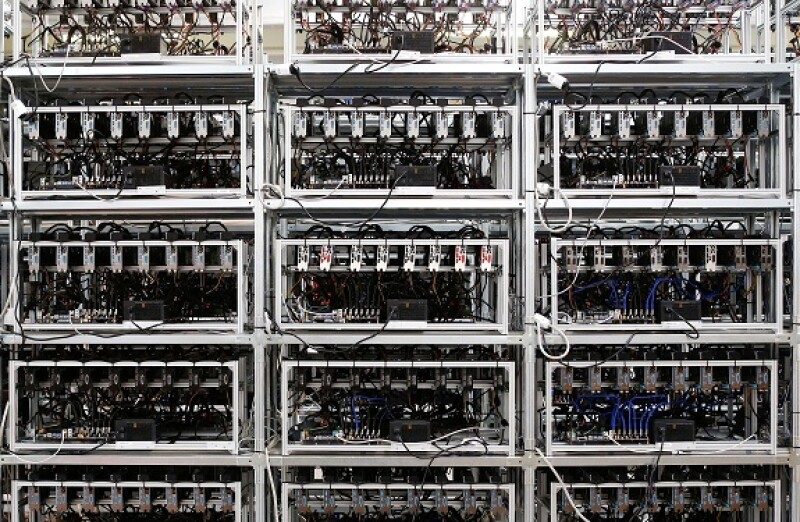

Digiconomist, an organisation that monitors the issue, estimates that the servers used to run Bitcoin (pictured) require 200 TWh of electricity a year, equivalent to 8% of all the electricity consumed in the EU in 2020. Ethereum eats up another 106 TWh, it reckons.

This energy use — for a completely new, non-vital and arguably financially dangerous activity — contributes grievously to climate change.

Different starting point

Rob Day, Spring Lane’s co-founder, was no crypto enthusiast. “I only took the first meeting [with Soluna] as a favour to a friend,” he said. “I’m a lifelong environmentalist. The overall picture of Bitcoin and crypto and their carbon footprint is scary.”

He started to get interested when he realised Soluna’s principals were not typical crypto bros but former wind farm developers. “When I heard the pitch I thought ‘this is not just about greenwashing, it’s about a tool to make more wind and solar farms get developed’.”

Soluna’s original motivation, Day said, was to solve a problem bedevilling wind farms.

In Europe, the popular perception is that wind and solar energy, which are intermittent, get prioritised in electricity markets because they are clean. So renewable generators can sell whatever they produce. Gas, coal and nuclear, easily switched on and off, are used to fill up the rest of demand. The grid is therefore as green as it can be at any time.

The reality is not as simple as that even in Europe. But in the US, markets are structured differently. Conventional generators tend to be guaranteed some sales, to ensure they are kept viable — supporters would say, to ensure security of supply, while critics would blame anti-green politics.

This means that quite often, when the sun is shining or wind is blowing, there is more renewable energy than consumers need. Wholesale prices fall to minuscule levels and can even go negative. Solar and wind farm operators may have to shut off some of their capacity, known as curtailment. Green electricity that could be generated is effectively thrown away.

Wide open spaces

Even without the electricity market rules, there would be some curtailment, because of physical constraints of geography and infrastructure — especially in a large country like the US.

“Texas has got beautiful wind and solar resources out in the western part of the state,” said Day. “But everyone who needs the power lives in the lower right hand quarter of the state. So unless we can build large transmission lines, and that’s not going to happen soon, we’re going to have a hard time getting green energy to where it’s needed.”

Even if the grid as a whole could absorb surges of renewable production, they might not be able to get through local bottlenecks in the network.

Power lines may not be very complicated technology, but all the permissions required to build them across country make expanding capacity extremely slow and expensive.

As a result, wholesale prices in west Texas are often far lower than in the east. Meanwhile, the state has been racked by energy supply shortages, in extremes of both cold and hot weather.

The same pattern of clean generation pent-up away from population centres recurs on the US west coast and in the Mid-west.

Across all the US’s regional power grids, 3.4% of wind energy was curtailed in 2020, a figure that has risen over the past five years. In the Mid-west’s Miso network and Texas’s Ercot, the rates were 5% and 4.6%.

“That’s only an average,” Day pointed out. “It can be 15% or 20% with some windfarms.”

Turning the problem round

The energy industry is wrestling with many possible solutions to this problem, including energy storage — batteries, pumping water uphill, electrolysing water to make hydrogen. These will be needed, but are not easy. Batteries require a lot of certain chemicals, while hydrogen can be costly to transport.

Another approach is demand management — finding smart ways to shift demand to times when renewable energy is plentiful.

Soluna’s answer is to physically move demand to where the wind farms are. Homes and factories are not easily relocated, but data centres are.

At a pilot project in Seattle and a larger one in Kentucky, Soluna has tried out parts of its idea: build data centres specifically designed to soak up power from renewable producers facing curtailment.

Soluna has crafted a special form of power purchase agreement (PPA), under which its installations commit to take power farms cannot sell in the open market. The price is low, but for the farm, that is better than nothing.

Using the data centres for Bitcoin mining is an easy way to give them revenue. So far, Soluna itself has been mining Bitcoin at its first two sites.

Electricity is one of the main costs of this practice. Soluna reckons by using, for some of its power, electricity that would otherwise be curtailed, its energy costs for mining are half the global average of 4.6¢ a kilowatt hour.

Now Soluna is going one step further: building a data centre right next to a 150MW windfarm, at Briscoe (pictured) in the Texas Panhandle.

Picking winners

Spring Lane’s $35m commitment is likely to be disbursed in three tranches, which might be at one site or several. The firm’s innovative approach, described by GlobalCapital in 2018, soon after its founding, is to provide project equity. It invests, not in operating companies, but in project special purpose vehicles for leading edge sustainable technologies.

“Our model is to take the principles of traditional project finance and scale them down to a smaller scale than utility,” said Day. “There are $1bn cheque writers on Wall Street, eager to step in to project number 10. We are purposely a smaller cheque writer. Somebody has to step in and be the one to make that [bigger investment] happen. That developer needs not just capital, but to get seasoned revenues” so that it can pitch for larger sums. “We’re filling the gap where the billions can’t fit.”

Spring Lane’s first fund of $157m closed in November 2019 and has invested most of its capital with six partners, including a firm that turns manure into gas to use as transport fuel in California. Another makes compost; a third gasifies human waste from sewage. In April Spring Lane reached a $50m second close on its second fund, bringing it to $200m.

Its origination method is borrowed from the US solar industry: to partner with a trusted developer that can generate projects, then invest in a series. With Soluna, it will be the lead investor alongside co-investors.

The power of switching off

Soluna itself is listed on Nasdaq with a $130m market cap. Its data centre design is simple and modular. Most data facilities are designed to work 24/7/365. Soluna’s business is built around the intermittency of renewable power, so its centres are intended to be switched on and off.

We’re filling the gap where the billions can’t fit.

Rather than a handicap, Soluna sees this as an advantage. If a centre can be turned off, say for 10% of the time, it makes maintenance easier and allows the servers to cool down naturally, reducing the need for artificial cooling and further cutting the energy bill.

Mining Bitcoin is one convenient way to generate income — it can quite easily be interrupted. But Soluna also has its eye on what Day calls “the emerging category of batch computing, which Amazon Web Services and others are getting into”.

This is computing-intensive work that can be parcelled up and done in batches, for example at night — such as data crunching for pharmaceutical research or some video processing.

More fundamentally, being able to switch processing for a client from one location to another is a promising course for the data centre industry, as it learns to adjust to a future of more variable renewable energy.

Software has been developed to switch data and processing from place to place, for reasons other than energy and the environment, but putting this at the heart of the business model could be the way forward for the industry. Soluna sees movable batch computing as its long term vision.

To bring “truly green computing,” Day said, “you need to have multiple projects in multiple geographies. Some customers are going to want to have data in the US, some not in the US. If you have 12 sites and each one is working 90% of the time you can pretty much guarantee that at least one will be running at any time, so if you can switch around you can offer 100% uptime.”

Green or grey?

Soluna is not the first company to pair renewable energy with data centres — or cryptocurrencies.

“If you look at the history of the last 10 years of renewable energy purchases, it’s been quietly driven by tech giants signing PPAs,” said Day.

Google, Apple and Microsoft all have bold net zero emissions claims and pledges, which oblige them either to consume renewable power, or to buy certificates that are equivalent to doing so.

Meanwhile, the more socially conscious in the cryptocurrency industry are trying to improve the technology’s image as an environmental disaster. Many tokens have been launched that claim green credentials, such as Chia, Cardano and Nano, and there are companies that claim to offer green Bitcoin.

The most powerful way they can reduce energy consumption is to replace ‘proof of work’ with other methods of validation. Ethereum plans to change to a method called ‘proof of stake’ which it claims will cut its energy consumption by 99.5%.

Chia disagrees with proof of stake and has adopted ‘proof of space and time’, based on using spare capacity in members’ hard disk drives.

Despite these innovations, the crypto sphere is still energy-intensive, and most transactions are still based on proof of work.

Providers claiming to be sustainable have to be able to make a case that they are using clean renewable energy.

But that does not alter the fact that they are consuming energy, which otherwise could be used for other purposes. Top of environmentalists’ wish lists for reducing carbon emissions is using less energy, and blockchains tend in the opposite direction.

Green-minded tech giants and Bitcoin miners that use renewable energy — either from the general grid or direct from a windfarm — are “not making things worse, but they’re not being additive,” said Day. At best, their green efforts can reduce their carbon footprint towards neutrality.

Soluna, on the other hand, is “truly additive… What makes them different from anyone else saying they’re taking on the greening of Bitcoin [is the] mechanism to buy curtailed power.”

Stimulating infrastructure

Day believes Soluna’s model is not only financially advantageous but more genuinely green because it causes more green energy to be generated than otherwise would be.

In the short term, this extra energy is the curtailed power it buys, which without Soluna would be wasted.

An objection could be made that only a minority of the power Soluna’s facilities use will actually be rescued from curtailment. Even the worst hit wind and solar farms are only having to curtail 15% to 20% of their output.

Most of the time, Soluna will buy power from the adjacent supplier at market rates. It can even buy renewable power from the open grid, if the local wind farm cannot meet the data centre’s demand.

Nevertheless, using some curtailed power is still better than none.

A more powerful argument is that if wind or solar farm developers can be guaranteed not to have to curtail production, it makes developing and running them more attractive.

“These are supposed to be 30 year assets — if you are in the world of utility scale project finance you are not supposed to lose money on [them],” Day said. “It’s endemic across the industry that many of these wind and solar firms are suffering lost revenue through curtailment. That 15% to 20% makes a dramatic impact on their bottom line. [Soluna’s] floored pricing arrangement makes a big difference to the willingness of a wind farm developer to not shut down a windfarm prematurely.”

Even if few renewable installations are actually at risk of closure because of curtailment, “it’s not just about preventing [closure],” Day said. Rather, it could eliminate the situation where “that developer now says ‘I won’t build those next two’”.

And even if developers are lustily gung-ho, eliminating curtailment will help to reassure their banks and investors.

“One reason [more farms are] not being built is that on that next windfarm it will be even harder to sell power into a bottlenecked grid,” Day said. “A lot is not being built.”

Getting rid of curtailment would encourage developers to add more renewable capacity to the grid, increasing the penetration of renewables and displacing fossil power at times when wind and sunshine are not in surplus.

It could even be valuable at the political level. “We’ve all seen what happens with politics,” Day said. “Whenever they attack renewables it’s because they are not consistent, so they say ‘we need more gas-fired power plants’. One of the things people have identified for a long time is if you can take variable load and put it on parts of the grid, you can stabilise the grid. So it goes right at the heart of the criticism. Variable demand itself is a benefit to the grid that enables more renewable penetration.”

In Texas, where politicians have “made a particular point of saying that because of grid stability concerns natural gas and coal plants should have priority,” Day said, “we are now turning that on its head. We can say we’re solving that variability problem with renewables.”

Looking for friends

Soluna is small, but to its supporters, it has great potential. “They are partnering with some of the biggest project finance firms around their wind farms,” Day said.

The Briscoe site is owned by Capital Dynamics, the UK independent asset manager which has made over 200 clean energy investments in the US, mainly in solar, and 30 in the UK.

Developers, Day said, “are saying ‘actually with your solution we can build that windfarm’. It’s going to lead to more windfarms being developed — that’s why we think this is the first truly green approach to green Bitcoin. The others are about mitigating the damage — this is the first time somebody is using it to promote more windfarm and solar farm development.”

Of course, data too has to be physically transported. At the top end of the market are servers co-located with equity and derivatives exchanges, to make high frequency trading as fast as possible.

But for most purposes, large amounts of data can be piped over long distances much more cheaply than electricity. Building data centres can also create jobs in rural communities.

The big ask

Soluna’s model poses a challenge to existing claims for green cryptocurrencies. This is highly relevant to the financial industry, which is increasingly embracing Bitcoin, Ethereum and the whole decentralised ledger economy.

Whether you like crypto or loathe it, as Day said: “It’s there. Some of the biggest sovereign wealth funds and pension funds are making big bets on crypto. Wall Street banks are putting it on their balance sheets. Square changed its name to Block because it’s so focused on crypto and Bitcoin. It’s not going away.”

These firms will face the question: “What are you actually doing to make sure the bets you are making on crypto are not going to be at odds with your climate goals?” Day said. “Take Block — if Jack Dorsey [its founder] is serious about climate change, I would love for it to say ‘we’ll find more stories like Soluna, so we’re not doing greenwash’.”

Day is not exaggerating. Goldman Sachs’s website brands blockchain “The New Technology of Trust”, saying it is “redefining the way we transact”.

JP Morgan has a Blockchain Center of Excellence researching “use cases to develop in-house technology and pilot solutions across lines of business”. So far, these include an Interbank Information Network and a JPM Coin.

Claiming these activities are green just because they use renewable energy is inadequate. If they are more energy-intensive than much simpler conventional financial messaging, they are consuming renewable energy that otherwise could be used for essential activities such as lighting or powering machinery.

The stakes are about to get higher. The collapse of the Terra stablecoin last week, which took its total market capitalisation from $41bn to next to nothing, made calls for regulation of crypto markets, especially stablecoins, more urgent.

Janet Yellen, the US treasury secretary, told the House Financial Services Committee last week that stablecoins “present the same kind of risks that we have known for centuries in connection with bank runs”. The Treasury is working on how to regulate them.

If — or when — stablecoins do become regulated, the authorities will own the problem. They will have assumed responsibility, implicitly encouraging traders to look to regulators to uphold the stability of the system. And the regulators will have to deliver.

The United States must maintain technological leadership in this rapidly growing space

That injection of safety into the crypto market is likely to give it another huge boost.

As if that were not enough, it seems inevitable that central banks themselves will soon start to issue their own digital currencies.

In March, president Joe Biden issued an executive order declaring that “The United States must maintain technological leadership in this rapidly growing space” and setting out “the first ever whole-of-government approach to addressing the risks and harnessing the potential benefits of digital assets”. This includes the government and Federal Reserve developing plans for a central bank digital currency. Mitigating climate risks is among the policy priorities.

Last July, the European Central Bank launched a two year Digital Euro Project, expected to lead to its own CBDC. It believes it can do it in an “environmentally friendly” way, using much less energy than Bitcoin.

The leading firms in the financial industry, and its most powerful authorities, have hitched their wagons to the blockchain, while waving the green flag of net zero emissions. With every year that passes, the fudge and inconsistency inherent in those positions will come under greater pressure. Blockchain users will have to convince stakeholders that they are not part of the climate problem.

Through one mechanism or another, being able to point to new green energy generation they have caused to be created will be the best way to answer their critics.