Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is regularly lambasted and mocked in capital markets circles for his unorthodox approach to monetary policy. He believes that raising interest rates causes inflation, rather than quelling it. How quaint and self-defeating, the critics exclaim — he should obviously do the opposite.

On one level, the knockers are probably right. Turkey is now struggling with dangerously high inflation of nearly 50%. But, at 14%, the main central bank interest rate is already painfully high.

It’s easy to be glibly critical of an emerging market far away. But ask European market participants what the European Central Bank should do and they may feel less cocksure.

Inflation in February was 5.8%, for the fourth month in a row a record high since the creation of the euro. For years, the ECB’s monetary policymakers have been freewheeling the economic car downhill in top gear, desperately trying to urge some speed out of it. Now they are having to climb a rocky mountain.

Economic growth on the rebound from Covid is part of what’s driving inflation, but much of it is the constrained supply of energy, attributable to one V Putin, who has cut gas supplies to Europe since early 2020, leaving storage tanks echoingly empty.

That was before he attacked Ukraine, sending Brent crude to $110 a barrel, an eight year high. People and politicians across Europe are clamouring for help with the cost of living.

To make matters worse, the euro buys just $1.11, well below its average in the past five years.

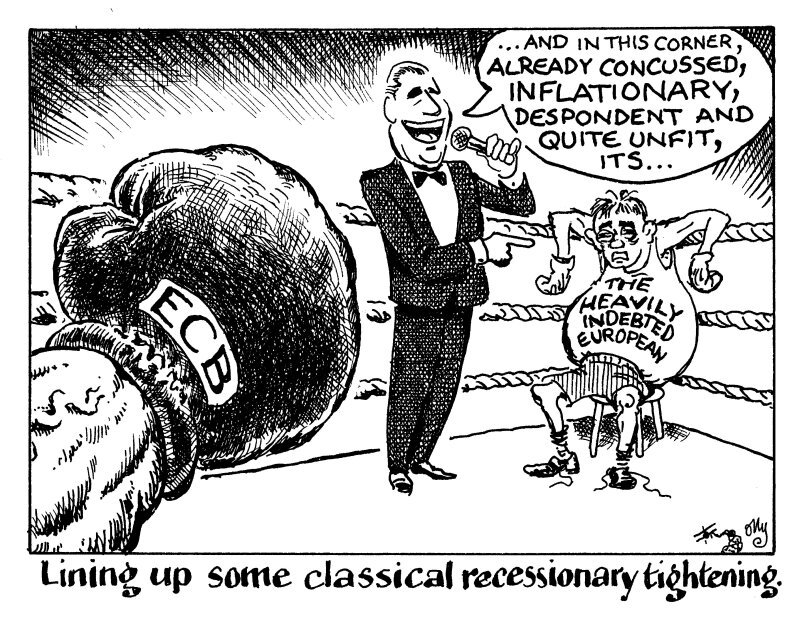

Classical economists would have no doubt — reach for the tightening levers. But if you were on the ECB governing council, would you really want to snatch money away from European mortgage and car loan borrowers right now? The pain would fall worst on the most indebted European nations like Italy, whose bond spreads and hence corporate refinancing costs would be likely to widen.

Tightening might lift the euro a little, but it probably wouldn’t soften energy prices at all — or those for food, which will also be pushed up by the war.

Not a nice choice, is it? Everyone is quite sure Turkey must take its medicine: recessionary tightening. But what about Europe? Gulp.