Everyone in capital markets seems to complain about order inflation. To judge by what they say when discussing it, neither issuers, nor investors, nor investment banks like it.

Yet, somehow, it’s everywhere. This week, even the traditionally sober Schuldschein market has fallen prey to the intoxicating habit. The mixed gaggle of smaller German and larger Asian and European banks that inhabit this corner of the capital markets are jostling at the bar, which is finally serving deals after a long dry spell.

Worthies who would never dream of doing it themselves are calling the practice “dangerous”.

Well, it is and it isn’t. Any investor that inflates its order does so at its own risk.

In the Schuldschein market, bids are supposed to be binding, and some banks remind investors of this regularly.

In the bond market and equity block trades, bookbuilds are done much more quickly, over a few hours. Prices are walked in from generous to tight as the book swells. Investors are notified as the guidance changes and can adjust their orders.

Especially in the bond market, they even get quite good information on how big the order book is, which should also help them calibrate the size of their orders.

Nevertheless, there was much hand wringing in the sovereign debt market in January when Spain had a book of €130bn for a €10bn deal, that then shrank to €55bn.

Was there any need to fuss? When a deal is oversubscribed, it is difficult to see what harm is done by investors inflating their orders to try and ensure they get a decent allocation — or by the related bugbear of issuers starting with very wide pricing to get lots of interest and then jamming it right in to the real price.

Yes, in theory bid puffing creates an arms race that could spiral to infinity, but fortunately, new issue orders are not — yet — placed by algorithms.

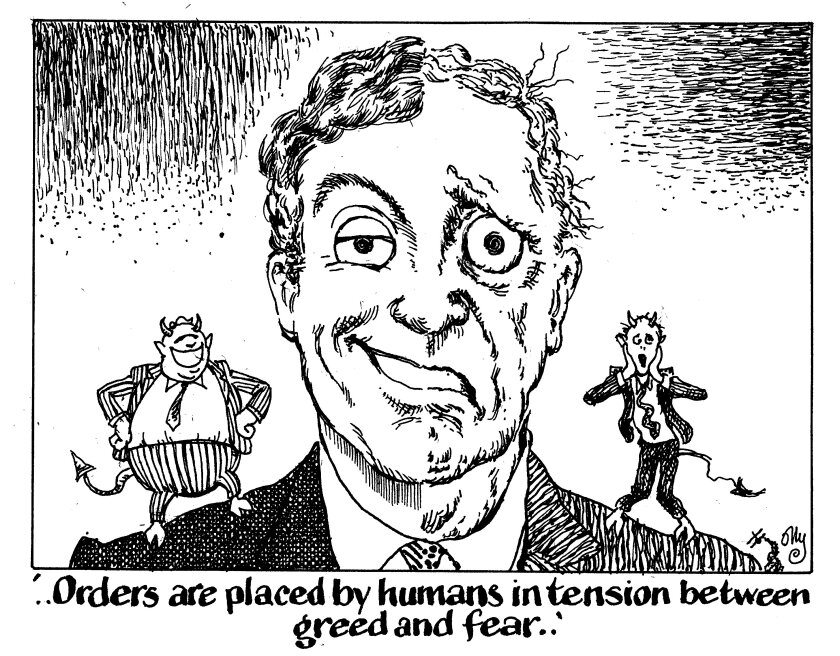

Orders are decided by humans in tension between greed and fear — the primal energy of markets.

In fast bookbuilds to large groups of investors, where it is difficult to predict demand on the day, starting pricing wide is a sensible tactic for issuers, and so is a modicum of order inflation for investors. How else are the market clearing price and optimal distribution of the paper to be established?

More importantly, it is hard to see how it can be avoided. Banks mulling over the Spain deal and a subsequent one for Italy admitted as much.

There is one way in which order inflation is unfair — those with deep pockets can gamble more freely. But such is capitalism — and if order book sizes are telegraphed, minnows can trim their risk in time. In any case, for virtually all issuers, allocations are also done by humans, who can exercise judgement.

A bigger problem for small investors is likely to be banks’ habit of treating them as insignificant riff-raff and zeroing their allocations, just for tidiness’ sake. This happens a lot in equity markets.

Nearly all of the time, order inflation may be annoying, but is a non-problem. That does not mean it should not be watched, in case undesirable consequences did appear.

If it were ever felt necessary to sterilise a market of order inflation, there is one simple solution. Inform all investors that on every deal, one order, chosen at random — or even one in 10 — will be fully allocated.

It might be very popular. Investors shy of risk would not play Russian roulette — but all of them might be glad to catch a golden ticket.