BPCE structured a new style of tier two debt this week, with features that were specifically designed to improve its risk-adjusted capital (RAC) ratio for S&P.

In many respects, the bond looked like a normal tier two: it had the same insolvency ranking, it had a final maturity date and its coupons must be paid.

But there were key differences in the new structure. Most importantly, a quarter of the principal will be permanently written down if BPCE’s common equity tier one (CET1) ratio falls below 7% of its risk-weighted assets.

The idea behind these sorts of triggers, more commonly found in additional tier one (AT1) deals, is that they provide a means for bonds to absorb losses before the issuer has reached its point of failure — while it is still a going concern, rather than a gone concern.

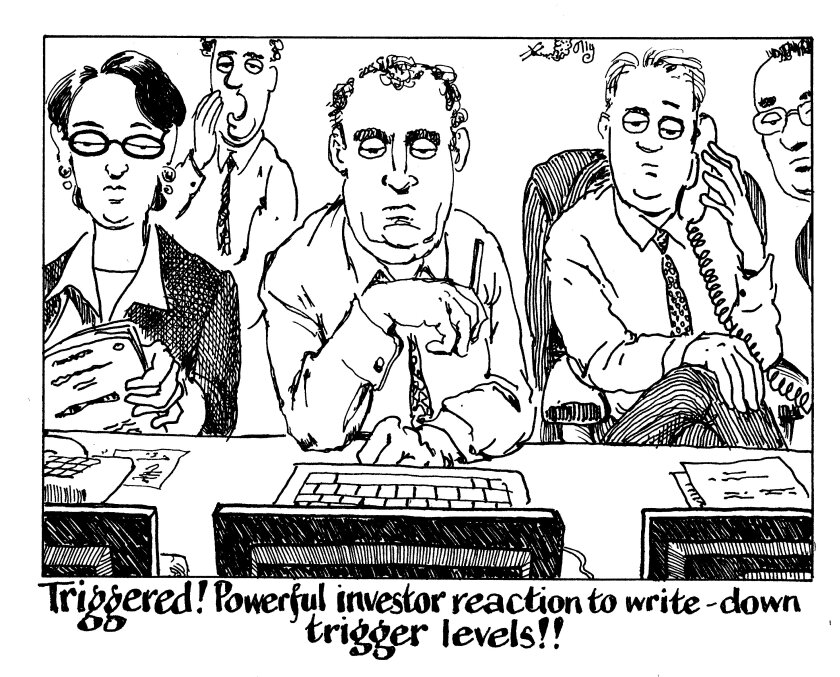

But market participants scoffed this week at the idea the write-down trigger made BPCE’s new tier two any riskier.

Bankers, investors, and rating agencies agreed the French bank would collapse long before it got anywhere near a 7% CET1 ratio, at which point all its bonds would be on the hook for losses anyway.

The same criticisms have long been levelled at the AT1 market, but BPCE’s RAC tier two sharpened the arguments by proving how little the triggers cost in real terms.

The issuer was able to price its transaction just 60bp wider than a standard tier two, and most market participants credited the premium to other quirks in the deal structure.

This should be a wake-up call for financial policy makers. If they are still serious about the concept of going concern capital, they will need to do much more to make sure trigger levels are credible.