In 2011, the combined market capitalisation of the four largest US coal companies was $30bn. Today, it is about $600m.

So notes Goldman Sachs in a study on the low carbon economy. But the US has not switched to clean energy. Even in 2040, according to the Energy Information Administration, coal-fired power stations are still likely to be producing 900 TWh of electricity, about two thirds of the present level.

The coal miners’ shares have been destroyed, not because their business has gone away, but because investors have seen the direction of travel and got out.

The result was a nasty hit for US savers and pensioners — but bearable, if they were diversified.

Now think about the market cap of the five biggest Western oil majors: $900bn. Oil and gas are of course crucial to our modern way of life — but so is coal. Is it a good idea to be invested in oil companies’ shares — or in their bonds?

Two years ago, that question would have seemed outlandish to many in the financial world, belonging more in a student common room. Not any more. The practice of integrating environmental, social and governance considerations into investment decisions is gaining hold rapidly.

For years, three reasons for doing this have vied: is it a moral imperative, a way to attract client money, or a driver of value?

For many commercial asset managers, this debate is over. Having moral feelings is tricky territory for them — their pitch to clients is: ‘we will make you money’. But they firmly believe they can make money better if they analyse issuers’ ESG characteristics.

Gains to be made

So far, there have been few glaring investment catastrophes like the US coal industry that ESG investors can point at, to justify their policy. ESG practice is more about biasing the portfolio towards better investments, which will outperform over time.

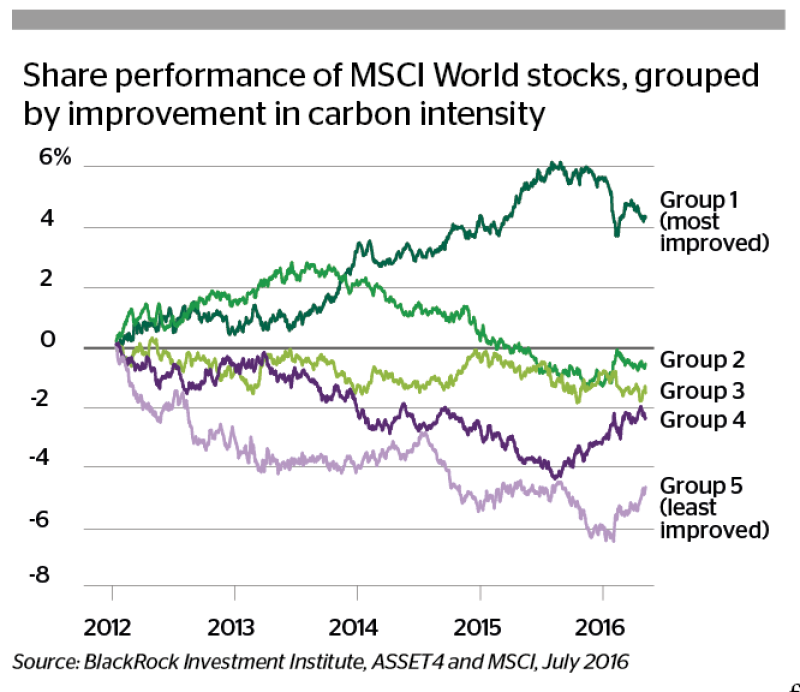

Professor George Serafeim at Harvard Business School says the degree of alpha an equity investor can generate with the right ESG strategy is “anywhere from 2% to 4% a year, after controlling for market factors like stock size, liquidity and momentum premiums”.

But many expect more big blow-ups. BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill and Volkswagen’s emissions cheating scandal are classic examples of corporate failure, which the vigilant — and lucky — ESG investor might theoretically have avoided.

“There’s been a change in the minds of many investors,” says Marcus Pratsch, head of sustainability research at DZ Bank in Frankfurt. “Take Western sovereign bonds — in the past they were seen as a safe haven, but the financial crisis in Greece showed that even sovereign markets are more characterised by volatility than stability. Some of the reasons are not just economic, but to do with governance or a deficit in social infrastructure, or even environmental issues. More and more mainstream investors are taking these sustainability issues into account.”

The ostensible purpose of most modern ESG investing is not to help the world on to a more sustainable path, but to make returns more reliably. But there’s a virtuous circle: if money moves to more sustainable issuers, it should help to green the economy more quickly.

“Capital markets have awakened and really know we have to play our role,” says Pratsch. “Investors not only see the challenges which lie in climate change, but have also realised there are huge possibilities to make money. One thing is sure: climate change will have an impact on returns, and more and more investors have realised it in the last 12 months.”

Acceptance is still by no means universal. Pratsch says there are still investors in Europe who take little interest, while Asia is perhaps five to seven years behind Europe. On a recent trip to Singapore, he found some mainstream investors stress-testing their portfolios with regard to climate change, while others focused only on short term returns.

Across the portfolio

ESG integration is an increasingly common style of responsible investing. It involves systematically applying ESG analysis to all investments you consider, often in the form of scores, and using that extra non-financial data to inform the investment choice.

Kaan Nazli, senior economist at Neuberger Berman in the Hague, belongs to a team running emerging market bond funds that has been developing its own ESG techniques for 10 years. “We do it because it’s unavoidable, especially in the EM context,” says Nazli. “If you don’t look at the ESG factors you will miss a big part of the credit picture.”

Neuberger Berman was already underweight Turkey before the failed coup in July that led to a harsh government backlash. “We were seeing the political pressures building and international relations worsening,” says Nazli. Meanwhile, it had been bulking up on Argentine debt for two years — well before President Mauricio Macri was elected in December 2015 — prompted by strengthening indicators for rule of law and ease of doing business.

Financial indicators for Argentina have yet to catch up with the ESG ones. “They still have to bring down inflation, put the budget on a solid footing, debt has been rising,” says Nazli. “But the ESG [signals are] too important.”

Ever onwards

Acceptance is still by no means universal. But the march of ESG is only going one way. In August, BlackRock added its prestigious weight to the credibility of ESG by publishing a paper on Adapting portfolios to climate change.

Hans Biemans, head of sustainability, markets at Rabobank in Utrecht, says he always begins a meeting with a corporate client by discussing, not green bonds, but the company’s sustainability ratings from specialist agencies and its rating for involvement in controversies.

“Most of the treasurers and CFOs are not aware of it,” he says. “It doesn’t mean they are not interested. They are often very surprised and immediately take action. Often if you have a low rating it’s not about bad performance but a low level of transparency.”

So far, even issuers with bad ESG scores can issue bonds. Biemans cites a deal that was four times oversubscribed — but he still told the issuer that some investors in the Benelux, France, Switzerland and Nordic region would not touch its bonds.

“Talking about ESG used to be seen as a career risk. Now the risk is not knowing what it’s about,” says Archie Beeching, senior manager, investment practices for fixed income and infrastructure, at the Principles for Responsible Investment organisation in London.

More than half of all professionally managed investment assets in the world are now owned or managed by signatories to the Principles. In the annual reporting cycle at the beginning of this year, about 250 fixed income investors participated.

They will all be ranked by the PRI organisation for how thoroughly they do responsible investment, on a host of indicators. “We are encouraging asset owners to ask asset managers to see their assessments,” says Beeching. “It’s driving transparency in the industry.”

The discipline of ESG investing is very different from the urges that drive the green bond market, where investors want to feel their money is having a certain effect. While the green bond community craves a standard definition of green, in ESG “there are as many ways of doing it as there are analysts out there,” says Beeching. “That is the way it should be. These are investment factors or themes, which are not traditionally measured in financial terms, but they have a cost or benefit.”

Find out what matters

Breckinridge Capital Advisors, a high grade fixed income manager in Boston, started applying ESG analysis systematically about six years ago, as a way to spot risks. Even now the firm feels somewhat unusual in that asset class for doing ESG.

“Our basic investment philosophy is that we want less correlation to risk assets,” says Phil Newell, the firm’s head of consultant relations. “So getting a more holistic view of the bond issuers we are selecting for client portfolios has been woven into our DNA. Markets have changed, the economy has changed and demographics have changed, to the point where things other than fundamental financial analysis can have a significant material impact on business operations and even create a risk to payment of principal and interest.”

As Breckinridge felt its way, it came across the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board, and realised the importance of its work on materiality.

“Barclays’ environmental footprint is not as material as Chevron’s,” says Newell. “You need to think about things that are material and impactful to that issuer. Data security for financial companies, access to medicines and pricing policies for pharmacies — you can look in the newspapers and see how jacking up prices on drugs can cause a backlash, not just among consumers, but in Congress or regulatory bodies.”

Wal-Mart has improved its employee relations, including giving staff a pay rise “in response to an outcry about how they were working with employees”, says Rob Fernandez, director of ESG research at Breckinridge. The push may have come more from public opinion than investors, he concedes, but although the pay rise has caused a “dip in profitability”, they are “seeing improvements in lower staff turnover and better customer service”.

Each of Breckinridge’s 16 analysts is supposed to do the job of an ESG analyst as well — rating credits in the conventional way, and then adjusting that rating up or down, depending on ESG factors material to that name.

The resulting rating dictates the minimum spread Breckinridge will want to be paid to hold that bond, and below which it will look to sell.

The firm has about 50 fossil fuel-free investment mandates from clients, but they are small, totalling about $250m.

Breckinridge has been doing engagement with its issuers for several years, speaking usually to the investor relations team and sometimes also to the sustainability officers. “The quality of the conversations has really improved,” says Fernandez. “Sometimes they are very appreciative of our feedback — they struggle themselves with what’s material.”

In a series of papers, Prof Serafeim at Harvard has explored how to spot which ESG factors actually matter to a company’s performance.

A company can profit if it provides solutions to environmental and social problems, and these issues can affect its cost of capital by changing its risk profile. Investors must try and measure and capture this.

“People have been trying to construct composite scores of a myriad of ESG issues that the company might be facing,” Serafeim says. “It turns out that only a small subset of these are financially material, so most of the data capturing is quite irrelevant. What we showed was that if you identify what is financially material on an industry by industry basis, then you can use this information to predict returns and accounting profitability in the future.”

BlueBay, the London-based fixed income manager, hired its first permanent ESG lead in 2014. My-Linh Ngo, who got the job, had previously done ESG in equities at Hendersons and Schroders. “I learnt that I had to modify what we did in equities,” she says. “Some aspects are transferable to fixed income, others not.”

But fundamentally, Ngo believes “ESG risks are probably more relevant for fixed income, because we have no upside. We could lose money if the credit gets downgraded, not only if it defaults. It’s very much about having confidence that management are able to repay us. As such, governance is the number one issue debt investors look at.”

Unlike Breckinridge, BlueBay does not yet have a fully integrated scoring system that combines financial and ESG data. Like its rivals, it uses external data, such as from MSCI, to identify high and low performing companies. The firm’s risk takers consider that information when deciding whether to buy or sell a certain security.

“We look at this as a value proposition,” Ngo says. “With equities you tend to have one risk profile, and often it’s simply a case of ‘you’re either in or out’. With fixed income you have access to so many more instruments — there are different maturities, you could be senior or subordinated, you could even go short through CDS. These each have different credit and ESG risk profiles — so the decision on whether to invest comes down to how nuanced the ESG risk is for that specific bond.”

To boldly go…

In the past year, there has been a huge change in the rating agencies’ stance towards ESG. Standard & Poor’s had always considered ESG issues if they were relevant to credit risk, and had begun to make this analysis more systematic and overt, with respect to specific risks like carbon and water.

This process, paralleled at Moody’s, has continued. But S&P has now bought Trucost, an environmental data company, and launched two new products that depart completely from its métier of evaluating credit risk.

Out for consultation until October 17 are S&P’s ESG Assessment and its Green Bond Evaluation. “They reflect the demand we think exists for looking beyond credit risk, in the world of ESG and green finance,” says Mike Wilkins, head of environmental and climate risk research at S&P in London. Feedback from investors has been good, he says.

The ESG Assessment will rank issuers on a five point scale for their exposure to ESG risks, which may not yet be material to credit risk, on both medium and long term horizons. It will be an alternative to ratings from firms such as Vigeo and oekom. Issuers will pay to be rated.

The Green Bond Evaluation, unlike Moody’s similar product which just covers governance and transparency, is designed also to evaluate the environmental impact the issuer attributes to a green bond.

Coming your way, like it or not

But perhaps the biggest change in the past year is a rising consciousness that ESG analysis is not just something investors do to companies, with or without their co-operation. Increasingly, companies have to provide ESG information, and in an increasingly standardised way.

The Hong Kong and Singapore exchanges are issuing requirements for listed companies, and in Johannesburg firms already have to integrate ESG factors into their main financial reports.

From 2018, listed companies in the EU will also have to disclose some ESG issues.

In the US, the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board is on a long term mission to develop a set of accounting rules, analogous to those for financial performance.

Janine Guillot, director of capital markets policy and outreach at SASB in San Francisco, joined the group from Calpers because “if you want to integrate ESG with rigour and at scale, it requires data — comparable, consistent data”.

SASB’s dream is to have standardised reporting forms, so investors could easily weigh up comparable companies.

“We want standards that identify disclosure topics that are material, decision-useful and cost-effective,” says Guillot. SASB has classified companies into 79 industries and developed different standards for each, which emphasise what is relevant to that industry, leaving out the irrelevant.

“Some companies have started to use them, but our end goal is that companies would disclose this information in their mandatory financial filings,” Guillot says.

A major obstacle will be persuading companies that they would not incur frightening legal risks by including SASB information in their 10-K filings. Guillot argues that often they are disclosing the information already, and that standardisation should protect companies.

Nowhere to hide from risk

Coming to meet SASB half way are the regulators. Nothing is changing faster in climate finance, in the West and in China, than awareness of climate risk. This is the idea that all, including investors, need to start thinking seriously about how they might lose money from climate change. “The risk agenda is now relevant and material,” says Nick Robins, co-director of the UNEP Inquiry into the Design of a Sustainable Financial System.

Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, has won great publicity for this question with speeches warning of the danger of fossil fuel assets becoming stranded — and by the Bank of England’s investigation of how prepared the UK insurance industry is for climate change.

The Bank and other financial supervisors now realise climate change poses a direct risk to financial stability — and this could strike overnight.

If a disaster suddenly made investors reassess the risk of holding climate-sensitive assets, such as oil companies and power stations, there could be massive losses in share and bond portfolios. Just as with the coal industry, the tipping point in investor sentiment could come long before conventional financial metrics seem to warrant it.

“One of the big triggers in the coming years is going to be that divestment thinking will increase,” says Pratsch. “We’ve already had it for apartheid and tobacco, but in recent years it has increased for coal. Some investors have announced they are getting out of coal. I know of others who have not announced it to the press, but are starting to screen their investment portfolios and do fossil fuel divestment step by step."

The guardians of financial stability now increasingly see it as part of their duty to make sure the institutions in their care are on watch for such events, and have planned for the risk, as they would for other risks.

The G20’s Financial Stability Board has set up a Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, which will report to the FSB in mid-November.

Jon Williams, a partner at PWC and member of the Task Force in a personal capacity, says it will devise a framework for forward-looking financial disclosures that companies can use to show stakeholders how they are planning for climate risks — direct physical damage and the impacts of changing policy.

“What we’re essentially saying is: ‘what is your governance around climate change? What is the role of management? How does that inform your strategy and financial plan? How do you integrate it into the way you manage risk? And what are the metrics you’ve chosen to measure climate risk and opportunity for your business?’”

G20 finance ministers could decide to adopt its ideas and make them law in different countries. France should find this easy — its Energy Transition Law of 2015, widely praised by climate finance specialists, already requires institutional investors to report their carbon emissions.

ESG is already going mainstream, as investors choose to adopt it. New information tools, like SASB’s standards and S&P’s assessments, will ease that process.

And it now looks likely that financial supervisors will force all investors to adopt an ESG mindset, at least towards climate change, in the next few years.

At that point, if everyone is doing ESG, its power to earn investors extra value by helping them spot things early will logically be eroded. But ESG specialists don’t mind.

“That alpha should disappear, and be fully reflected in the cost of capital,” says Serafeim. “But we will have provided companies with market-based incentives to have a more positive societal impact, which from my perspective is a fantastic thing.”