The whole world has agreed: climate change is an urgent threat and all must act to tackle it.

Well, not quite the whole world — this being humanity, perversity is central to the story.

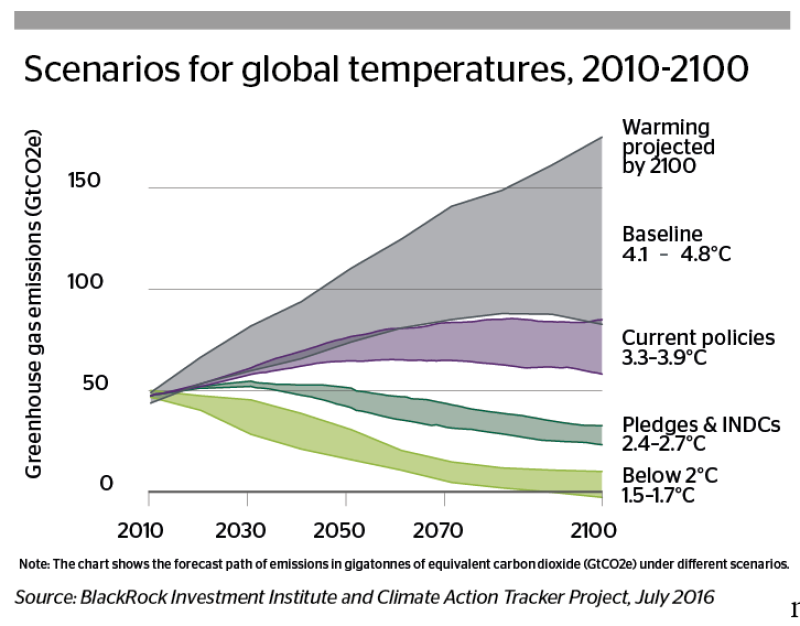

But the Paris Agreement, adopted on December 12, 2015 by 197 countries, commits them to holding global warming to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and to “pursue efforts” to keep warming to 1.5°C.

If that could be achieved, the existential threat of climate change could be transmuted into something kinder — still requiring a completely new way of life and enormous disruption, but permitting the continuance of modern civilisation.

Considering that a year ago it was far from certain an agreement could be reached, Paris was a huge win. For the first time, all countries are — literally — on the same page.

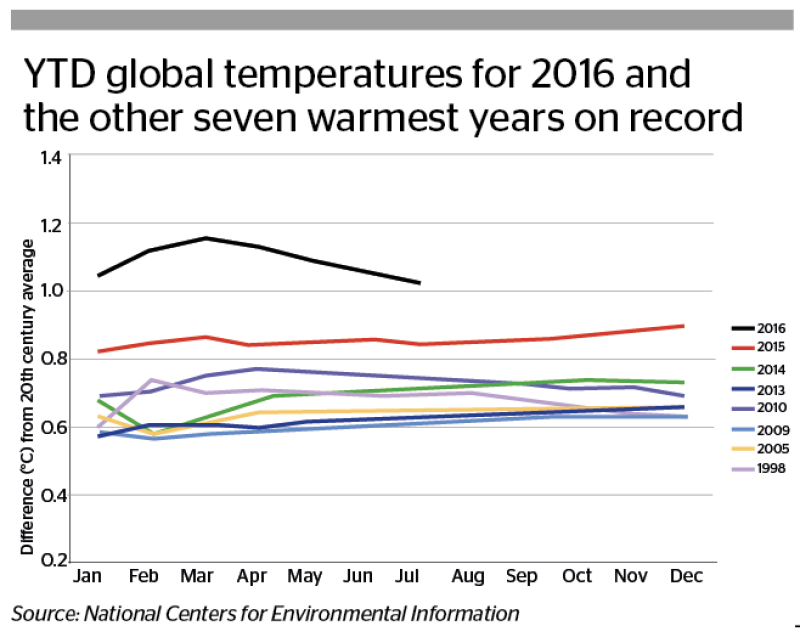

They have agreed to the temperature targets, set up an architecture for supporting, verifying and revising the Agreement, and set out what each country plans to do. Those plans — Nationally Determined Contributions — are all different, and vary greatly in ambition. But they are a start. Crucially, the Paris Agreement recognises on its first page that the NDCs do not go far enough. They would lead, in fact, to 55bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent being emitted in 2030 — up from 48bn in 2012 — and probable warming of 3°C-4°C or more. Countries will have to become much more ambitious, quickly, even to achieve 2°C.

Trump lies in wait

Climate specialists have been filled with optimism since Paris, but one date looms that could prove as critical as December 12. On November 8, Americans will elect a new president, and the Republican candidate Donald Trump has said he would reject the Paris Agreement.

Trump has a habit of saying radical things and then changing his mind, but that is little comfort.

The Agreement enters into force 30 days after the moment when 55 countries, producing at least 55% of global emissions, have ratified it. A leap forward came in September, when the US and China ratified together, meaning 27 countries producing 39% of emissions are on board.

If the 55-55 threshold can be reached before the US election, and thus before the COP 22 meeting in Marrakesh in November, Paris could come into force before the new US president takes office on January 20.

Legally, it would then be difficult for the US to get out of the Agreement. It would be a four year process. But such details matter little. Politically, if a President Trump wanted to, he could kill US participation instantly.

“The US remains the key country for climate action,” says Janos Pasztor, who was UN assistant secretary-general for climate change during the Paris negotiations. “If that country leaves, it would have a very negative impact on the implementation.”

The big question would then be how the rest of the world reacted. Above all, China would have to decide: should it renege on its own commitments? Or reprimand the US and press on, becoming an international champion of climate action?

“I would be crazy if I said I knew the answer,” says Pasztor. “But I think the indications are from the behaviour of the Chinese delegation and ministers that they are quite serious about it. While there was some give and take — because the US engaged, they engaged too — China is on the path domestically to address climate change. China’s position has evolved a lot in the last five years — it’s much more climate-positive.”

Damian Ryan, acting CEO of the Climate Group, an NGO, in London, agrees that “China is not moving away from the trajectory of decarbonising its energy sector — they are committed 100%.”

But he adds: “From a geopolitical perspective, China is not yet in a position where it wants to take on the mantle of global policeman. They might say ‘we are still going ahead’, but I don’t think they would step up to the plate and be the leaders.”

Jens Clausen, senior climate change adviser at Greenpeace in Copenhagen, believes China is in the process of becoming a climate champion. “China has cut down on the use of coal for three years in a row,” he says. “They are blowing all renewable energy records out of the water. Even if the US elects Trump and rolls back, my sense is that China will keep doing it because it’s in their self-interest, it has a palpable effect on everything from water to health.”

Brexit adds to Europe’s angst

Europe has long been in the vanguard of environmental consciousness, but here the politics are not easy, either.

The European Union promised in Paris to cut emissions by “at least 40%” from a 1990 baseline, of which the first 19% had already been done.

How the decarbonisation effort is shared among member states still has to be thrashed out. So an early ratification of Paris is unlikely.

“Especially the central and east European states have a massive issue with huge emissions cuts,” says Sabrina Schulz, head of the Berlin office at E3G, a sustainability consultancy. “They will say they can’t deliver, or look for trade-offs in other policy areas.” Clausen adds that even Denmark is fighting its corner, and says the effort sharing talks could go on until 2017 or later.

The UK’s vote to leave the EU has made things even more difficult. Britain might choose to stay with the EU for Paris purposes, but with the whole UK-EU relationship in flux, an early decision looks unlikely. More probably, the UK will have to produce a new NDC of its own.

Already, environmentalists are dismayed that the EU’s negotiating document for effort sharing has silently dropped the “at least” ambition and is aiming just for a 40% cut.

That would mean lowering per capita emissions from 9 tonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2012 to 6 tonnes by 2030. That rate, applied across the world, would still cause runaway warming.

“We must not create a lock-in [of insufficiently clean technology],” says Schulz. “There needs to be flexibility so you can later make the targets more ambitious, without having to renegotiate the whole agreement.”

Getting down to action

If the immediate political pitfalls can be got over, and Paris becomes a reality, the focus will shift to implementation.

“Many countries, including in Africa and Asia, are working very hard on strategic plans, finance plans, means of implementation,” says Grant Kirkman, head of relationship management for sustainable development mechanisms at the UN Climate Change Secretariat.

“It’s going to be very difficult to implement, but you can distinguish between two phases,” says Pasztor. “In the short term, it’s pretty clear what countries have to do — renewable energy, energy efficiency — there have been fantastic developments in the last few years, but we need to move much faster.”

But Paris has two medium to long term goals. Besides keeping warming to ideally 1.5°C, the world has to achieve zero net emissions by mid-century. “That is not going to be easy,” says Pasztor. “We need nothing less than total revolution — developing lots of new technologies and organising ourselves as societies to make better use of them. I have no doubt we can shift entirely to clean energy — my worry is the path to get there without overshooting the 1.5°C-2°C goal too much.”

One group who share that sense of urgency are the V20 — a gathering of finance ministers of countries particularly vulnerable to climate change, such as island states like the Philippines and Tuvalu.

The group met for the first time in October 2015, but already it has grown to 43 countries with 1bn people between them, including Bangladesh, Costa Rica, Kenya, Morocco and Vietnam.

The V20 successfully pushed for the 1.5°C ambition to be mentioned in the Paris Agreement, and could become a vocal pressure group for bolder action by rich countries, to aim for that 1.5°C target.

They are demanding that climate finance, which now goes overwhelmingly to mitigation (cutting emissions) be split 50-50 between mitigation and adaptation.

They also want to construct a V20 Risk Pooling Mechanism, to protect each other financially from storms, floods and droughts. Over half their populations have no access to insurance of any kind.

Not enough money?

The task is huge, but those pushing for action on climate change are unanimous about one thing: all over the world, in all sectors of society — government, corporations, individuals — more and more people are getting the message.

“In 2018, governments need to review what they have done and what they need to do [under the Paris process],” says Ryan. “That’s going to be critical, and it’s the role of non-state actors to help provide that comfort to political decision-makers that, yes, economies can do it, that it’s good for business, that they can take the next step and increase their ambition.”

Central to the fight against climate change is finance. One of Paris’s three key tenets is “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”.

The hubbub about green matters in the financial world keeps getting louder, and reached a crescendo in September when China chose green finance as its leading topic for the G20 meeting in Hangzhou.

Estimates of the money required can sound daunting. For instance, $1tr of investment in clean energy is needed every year until 2050 to limit warming to 2°C, while the world needs to invest $12.5tr a year to meet the broader Sustainable Development Goals, also agreed in 2015.

But the industrialised world — including China — has for years had a glut of liquid capital, and a shortage of things in the physical world to spend it on. Central banks trying to stimulate demand have added about $11tr of invented money to this lake since 2008.

In global bond markets, some $6tr of new syndicated bonds are likely to be issued this year, mainly in rapid sales where investors commit in a few hours because the debt is from investment grade rated issuers they are familiar with.

What this means is that if projects are financeable — meaning economically viable, and rateable — they will get financed. The propensity of capital to gush wherever there is money to be made is amply shown by the 90% increase in US oil production in seven years since 2008.

“We know how vast the environmental challenge is,” says Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative, an NGO, in London. “But we can convert it into investment opportunities. This could be a 30 year investment boom in green technology.”

Jon Williams, partner, sustainability and climate change, at PricewaterhouseCoopers in London, has the same conviction: “If I was in a bank, I would be saying: ‘this is the best opportunity ever — how do I find the deals I can finance?’”

Yet in 2015 in Europe, $49bn was invested in renewable energy, down from $123bn in 2011, when solar booms in Germany and Italy were in full swing. China’s investment, however, hit a record of $103bn, more than double that in the US, a much richer country.

The problem is not availability of money, but that not enough green projects are being brought to a financeable state. In the industrialised world, this is largely because of government policy.

The first recommendation of the G20’s Green Finance Study Group has nothing to do with the financial world itself. “It’s the need for clear policy signals from government to the financial community,” says Nick Robins, co-director of the UNEP Inquiry into the Design of a Sustainable Financial System.

Rather than continually changing tack on climate policy, governments need to set a long term direction and stick to it. Predictability would give the financial sector confidence to invest, and close the gap between the large new infrastructure needed and the small amount being spent now to bring it about.

Bridging the north-south divide

In developing countries, the challenges are greater. The pots of money in Europe, Japan and North America are far away, domestic capital in the smaller and poorer countries — including most of Africa — is scant, and legal systems and policies are not always conducive to investors.

Here, closing the investment gap requires different work — much easier to diagnose than to achieve.

“The opportunities in the developing world are vast,” says Kirkman. “A lot is being domestically funded, either privately or with development assistance. There is entrepreneurial spirit and a willingness to work with international finance. But there are financial barriers to some of these markets. The cost of capital is often high in countries where most of the potential lies and this needs to be urgently addressed by the international community.”

Capacity building is needed, so players in developing countries develop the skills to bring projects to fruition and secure international finance. So are legal reforms, to strengthen local capital markets.

But there is work for the financial sector to do, too. Christopher Flensborg, head of sustainable products and product development at SEB in Stockholm, points to “a gap in how to design or aggregate projects in risk and scalability so that they become attractive to international investors.”

More talk than action

After Paris, when the investment world had expressed so much enthusiasm for the green push, Paul van de Logt, senior climate policy adviser in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, visited big institutional investors, hoping they would invest alongside the government in green projects in the developing world. He found many were unwilling to go outside their traditional mandates, for example to buy investment grade, OECD securities.

“My main message to investors is: ‘you say you want this to happen, but it’s not going to happen unless you put in the capacity, in personnel, money and risk appetite, to do it’,” van de Logt says. “Of course investors can’t just take a lot of risk. But there are lots of options out there.”

Climate finance specialists all want public sector finance to provide credit enhancement, so private capital can flow in with safer senior lending.

Williams says he made this point to the Green Climate Fund, which has $10bn to invest. “It should be prepared to take sub-investment grade risks, to make unbankable deals bankable,” he says. “This is not an excuse for lazy capital markets to say ‘guarantee our returns’, it’s about saying ‘what are the risks the private sector can’t take?’”

But although the multilateral development banks have experience in such techniques, there has still been no breakthrough on multiplying their activity to the scale required.

FMO, the Dutch development institution, is backing a programme called Climate Investor One, in which the public sector takes a first loss position. The fund is soon to reach its first close. But van de Logt says: “It is still challenging to attract investment into emerging markets.”

Pushing and pulling

So far, for all the good will in the financial sector, it has done little to accelerate the green transition by pulling more projects into being, through its own eagerness to fund them. Its pulling power is weak, since investors need safe risks and decent returns, which can only be provided if governments get the policies and legal environments right.

But there is another way the finance world can act on the economy: pushing it. “There will be more pressure on the net achievement of the financial sector,” says van de Logt. “It’s not just what you do green, but what you do grey. The British, the Dutch central banks, they’re all doing research into the climate sensitivity of the financial sector — the whole stranded asset discussion.”

As is explored more fully in this report’s chapter on ESG integration (see pages 6-8), financial supervisors now realise climate change poses a direct risk to financial stability. They are making banks and investors be proactive about managing that risk, whether it comes directly from climatic events, or from changing policy.

If investors are forced to look climate risk squarely in the face, self-preservation is likely to make them start shifting their dollars to greener assets, sooner rather than later.