In the immediate aftermath of 2008, investment banks had very little with which to start repairing their threadbare images. Corporate responsibility and sustainability were elegant solutions that could start to put the shine back on the chrome, without a lot of downside risk.

Seven years later, the banks continue to project an image of concerned citizen across everything from financing windfarms to charitable giving to community outreach. Yet trying to discern the effectiveness of these programmes is a bit like reconstituting the vegetables in a bowl of minestrone.

What many stakeholders — notably the general public which is the object of this charm offensive — may want to know is: does the good that comes from a bank’s corporate responsibility and sustainability programmes outweigh the bad that goes on in their banking and trading activity? Investors who follow environmental, social and governance (ESG) policies are also interested in this question.

However, it is, unanswerable. How much mentoring in deprived areas of East London makes up for lending to a coal-fired power station, or fiddling an interest rate?

As Usman Hayat, director of Islamic finance and environmental, social and governance at the Chartered Financial Analysts’ Institute, puts it: “The main issue is — are you able to act responsibly as go you about your business? If you are found to be making headlines for the wrong reasons regarding your core business, such as rigging markets and benchmarks, then the fact that you gave donations to charities and that your employees were found to be planting trees means little, if anything.”

As Hayat points out: “Giving out small fractions of investing banking profits to charities is much easier, and therefore far more tempting, than cleaning up how you earn your profits in the first place.”

But that is not enough. Regaining the public trust will require “demonstrating a commitment to responsibility in the core of the business, that is abiding by law and ethics in your day to day work”.

Rather than trying to weigh banks’ virtuous corporate responsibility efforts against any sins they commit in daily life, it may be more pertinent to think about the two separately.

Are the banks’ volunteering and pro bono efforts beneficial and effective? And, in a very different way, how well are the banks doing at being responsible in their core businesses?

John Hodges, a managing director at BSR, a global non-profit business network, acknowledges that banks may have been attracted to social responsibility for PR reasons after the crisis, but does not think they have lost interest since. In fact, they may be becoming more thorough.

“Banks are more recently starting to make corporate sustainability more grounded in and related to actual business operations, as stakeholders become more educated and ask tougher questions of them,” he says.

That’s not to say there’s not a fair amount of puffery in the system. Hodges points to the tendency of all the leading US banks to promote their outreach to military veterans, encompassing everything from special banking services and employment programmes to direct cash contributions to veteran-focused charities.

“I think banks should be transparent about whether there is a real need, driven by the veterans having a hard time finding jobs, or whether this is a way to garner some PR by rewarding them for their military service,” he says. “I don’t mind that banks give special incentives to veterans; I just want them to be more transparent about why they are doing it.” (The unemployment rate for veterans in the US is lower than the overall national figure.)

Hodges is reluctant to criticise individual banks, but points out that there’s an information gap — the banks choose what they want to highlight.

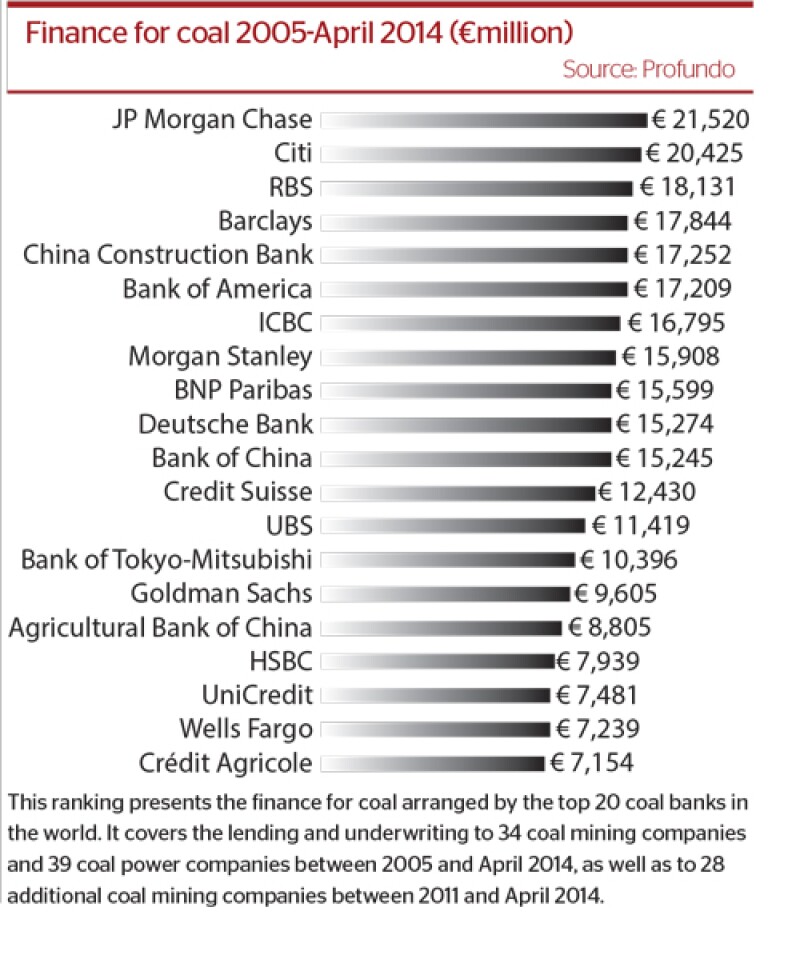

“It’s great that banks are reducing their paper consumption and investing in green bonds,” he says, “but what about the deals they’re not talking about?”

Engaging the staff

For any social responsibility programme to be more than window-dressing, it has to be driven into the culture of the firm. It’s clear from the posters and slogans you see if you visit many investment banks that they are trying to lead staff to adopt the philosophy of being a good corporate citizen.

Barclays launched a citizenship programme in 2010, but it grew in importance two years later when Antony Jenkins took over as chief executive after Bob Diamond left amid the Libor scandal. Jenkins launched a drive to change the bank’s culture that was so broad and intense that many felt it implied the culture was far more broken than it actually was.

Nevertheless, Barclays has embraced new metrics to track its progress in client connectivity, social and environmental impact and infusing ethical standards into its everyday business decisions.

“The metrics we use show we’ve taken that to a decent point, and we will continue to build on our progress so far,” says Kirsty Britz, director of group citizenship at Barclays. “We are also observant of best practice in other industries too. For instance, there’s a great deal we can learn from companies in the fast-moving consumer goods sector.”

An issue that is rarely talked about is the need to customise programmes to suit the different cultures on the retail and investment banking sides of large universal banks.

While the retail volunteer efforts are more grassroots in nature — painting football sheds or cultivating abandoned gardens — investment banks’ programmes reflect the more sophisticated, driven nature of the beast. In years past at the old Barclays Capital, volunteer programmes were built around providing management and governance for a group that assisted abused Asian women or installing the latest technology for a school in London that educated children with severe communications difficulties.

Such initiatives can also involve a bank’s core activities. In 2014, Barclays launched the Women in Leadership Total Return Index, designed to give investors exposure to US companies with gender-diverse executive leadership and governance. To be included in the index, companies must have a female CEO and/or at least 25% female directors, as well as meet market capitalisation and trading volume thresholds. Britz sees that as an example of a firm marrying its market expertise to a pressing social issue.

Opening the wallet

Not to be forgotten in this is charitable giving. “There is a frustration among charities in their dealings, not just with banks, but other corporates as well,” says Stephen Cook, editor of Third Sector, a magazine focused on charities and volunteering programmes.

“In the past, those charities would have established relationships directly with donors, in which they benefitted from either money or expertise,” he says. “Today, those same companies often have their own initiatives and simply don’t have to rely on charities to establish themselves as good corporate citizens.”

It is hard to track how much investment banks give to charity, but in its most recent report, the British Bankers’ Association says the six largest UK banks gave £366m to communities around the world.

Britz says Barclays has not reduced its long term commitment to supporting charity partners. “In fact, we’ve invested £250m since 2012 in our community programmes across the group, to support employability, enterprise and financial literacy for young people globally,” she says.

Britz admits firms could be better at communicating their giving strategies. “All corporates need to clearly explain the rationale behind their decisions to stakeholders on whether to initiate their own proprietary programmes or channel their giving through established charities,” she says.

The real deals

When it comes to evaluating banks’ social outreach, volunteering and charity efforts, banks could be forgiven for saying: “back off!” After all, these are voluntary, philanthropic activities. Private individuals would not want the good deeds they do to be measured or judged, so why should organisations? But their core business practices are a different matter. Here, the banks are operating for profit, and making real world decisions. The stakes are much higher, and investors and the public have a right to know what is going on.

A wealth of information and analytical tools is already available to help people — especially, but not only sophisticated investors — to make informed judgments. Many index providers, such as Dow Jones, FTSE and MSCI, offer detailed gradings and basketings to sort the sheep from the goats.

In a recent illustration of this, KfW, the German development bank, has decided that it will henceforward only award mandates for its green bonds to banks that win good ratings from Sustainalytics, a sustainability rating agency.

A much bolder move has been made by Commerzbank, ING and Westpac — the three large banks that have joined the Science-Based Targets initiative. This group of 114 companies have committed to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions in a way guided by scientists as compatible with avoiding global warming of more than 2°C — a more ambitious path than governments are following.

The initiative was convened by a UN body and three NGOs. Hodges says outside social agencies are playing an important role in monitoring banks’ sustainability performance.

“An organization like Greenpeace will ultimately look at [a] green bond issue and apply pressure where it’s needed,” he says. “ Similarly, the UK non-profit Oxfam is already reviewing the role being played by mid-sized and indigenous banks in emerging markets, that may have less sophisticated environmental and due diligence systems.”

Good marks — then a test

Hodges points to Citigroup and Standard Chartered as banks that have established credentials for their environmental efforts. One of the earlier moves to improve banks’ behaviour was the Equator Principles, launched in 2003. They are a risk management framework for environmental and social risk in project finance — essentially, safeguards against funding projects in the developing world that abuse local environments or people.

Citigroup was an early signatory to the Principles, and has taken matters a step further by insisting that all its banking and markets businesses adhere to them.

Standard Chartered, with its emerging markets-focused franchise, stands out for having a genuinely rigorous sustainability risk management programme, according to Hodges. “When others see a bank like that involved in a deal, there’s a comfort level that settles in,” he says.

However, StanChart’s credentials were put to the test last summer during a dispute with Greenpeace Australia over the bank’s role as lead financial adviser on the Carmichael coal mine project in Queensland, which is intended to be one of the world’s largest coal mines.

Greenpeace and Australian conservation groups launched a campaign against the project for two reasons. First, the mining of coal is something they find anathema, and second, the plans for the new port required to export the coal would damage the Great Barrier Reef. As bank after bank withdrew from the deal because of reputational risk concerns, StanChart found itself, according to the Australian press, the last man standing. It finally pulled out itself after an intense internal debate.

Sustainability is not just about pulling out of things, however — but also about stretching thinking to imagine what banks should be doing outside their comfort zones.

One such initiative is Long Finance, started by Z/Yen, a London-based think tank and consultancy. Rather than try and move the needle on what the banks are up to at the moment, Long Finance takes a more “clean sheet” view on what is needed to restore to a more rational, equitable economy.

Working with the City of London Corporation and Gresham College, its mission is to explore the question: “When would we know our financial system is working?”

One project is to seek creative financing solutions for the world’s urban areas. Entitled Financing Tomorrow’s Cities, it estimates that $57tr will be needed to adequately finance current and future urban areas over the next 15 years. Recognising that banks have little appetite at the moment for project financing, it has offered up a creative menu of public and private financing across multiple asset classes.

(Just) part of the solution

So now that the hills are alive with the sound of conscientious banks doing all that’s right for the environment and enriching the lives of millions, can we just sit back and watch the world become a better place?

Unfortunately not. The Queensland coal mine is a rare example where sustained action by civil society, including pressure on the banks and government, appear to have stalled a major project.

But the great majority of businesses that could be seen as socially or environmentally undesirable — tobacco, arms, oil and gas — are well supported by the financial sector.

And perhaps that is just as it should be. If you were to remove access to financing for the world’s biggest carbon emitters and environmentally unfriendly projects all at one go, the consequences would be disastrous.

Investment banks exist to serve their clients and are not the world’s environmental police. Ultimately, it is for the polluting or destructive segments of that client base to lead the way in greening themselves — and for governments to set policy so that they have to. The banks can only play an important supporting role.